Podcasts about kohelet

Book of the Bible

- 158PODCASTS

- 611EPISODES

- 33mAVG DURATION

- 1EPISODE EVERY OTHER WEEK

- Jan 25, 2026LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about kohelet

Latest news about kohelet

- Studien zu queeren Lesarten der Hebräischen Bibel AWOL - The Ancient World Online - Feb 3, 2026

- MAILBAG: June 17, 2025: How Megillas Koheles Points To This Date As “Eis Shalom” – The Final Pre-Mashiach Era The Yeshiva World - Jun 17, 2025

- Rothman aide’s book against ‘judicial nihilism’ sent to dozens of judges The Times of Israel - Aug 11, 2023

- A Coup d’État in Israel? : The Bitter Harvest of Colonialism CrimethInc. - Mar 27, 2023

- Who’s Behind the Judicial Overhaul Now Dividing Israel? Two Americans. New York Times - Mar 20, 2023

- Who’s Behind the Judicial Overhaul Now Dividing Israel? Two New Yorkers BizToc - Mar 20, 2023

- Who's Behind the Judicial Overhaul Now Dividing Israel? Two New Yorkers. (New York Times) memeorandum - Mar 21, 2023

- The Current State of Play in Israel’s Constitutional Showdown Lawfare - Hard National Security Choices - Feb 23, 2023

- ‘Moderate PAC’ is latest big-money push to keep Democrats in line on Israel Mondoweiss - Feb 18, 2023

- Jewish Tahrif Is A Double Negative Positive – OpEd Eurasia Review - Oct 15, 2022

Latest podcast episodes about kohelet

Zwei Weisheitsbücher, zwei verschiedene Arten, die Welt nicht schönzureden: Kohelet zieht Bilanz („alles Windhauch“) und beschreibt, wie wenig zuverlässig Leistung, Moral und Weisheit belohnt werden. Hiob ist das Drama: ein Gerechter verliert alles, Freunde liefern Erklärungen, Hiob weigert sich, Leid wegzureden, und fordert Gott heraus. Zentral ist die Gottesrede („Wo warst du, als ich die Erde gründete?“): keine Erklärung, aber eine Zumutung an jede einfache Rechnung von Schuld und Strafe. Zum Schluss der kulturelle Nachhall bis zu Goethes Faust (Vorspiel im Himmel) sowie ein Blick auf Engel- und Satanbild im Alten Testament im Vergleich zum Neuen. The post BBB 3 – Kohelet und Hiob first appeared on Bartocast.

We all sin! Sin is endemic to human nature: "There is not even a righteous person in the world who fails to sin." said Kohelet.But our chapter directs attention not to the sin of the ordinary Israelite but to the sins of leaders: The High Priest, the judiciary and the political leadership.Are their sins more egregious, or are they merely more prone to sin? Or are they possibly to set an example to us all?

S2E 13 What the Hell is Going On? (Jewish Answers Only)

The episode opens with the perennial prompt, "What the hell is going on?" and uses a small, concrete moment—an eighth-grader's intense anti-cheating check at a standardized test—to probe larger cultural drift. Are we lowering the baseline of civility and trust, or simply confronting old human problems in new packaging? The hosts toggle between the granular and the global: fraying norms in U.S. and Israeli politics, the difference between safety theater and integrity, and the unsettling feeling that structures once thought stable are wobbling. From there, the conversation tests three stances. One voice argues for historical moderation—by many measures the world is safer and fairer than in the past—while another insists that unprecedented anxieties are real, at least in our lifetimes. A third position says it may be stasis: humanity cycles through brutality and beauty. Jewish frames help hold these tensions—Kohelet's "nothing new," the dual memory of Sinai and the Golden Calf, "yeridat hadorot" versus the possibility of ascent, daily blessings that sanctify the mundane—alongside secular touchstones (evolution's cruelty, Viktor Frankl's meaning-making, and a Robert Hass passage on small consolations). The three Rabbis landson agency as the Jewish answer to metaphysical fog. Even without messianic guarantees, a "1% hope" that suffering can be reduced obligates effort: ask better questions, act in one's community, and keep resetting the moral bar. The podcast's purpose, they conclude, is exactly this: to take big, destabilizing questions, run them through Jewish texts and practice, and emerge not with neat solutions but with clearer bearings—and a renewed charge to get to work.

Welcome to daily Bitachon . We are now in our Sha'ar HaBechinah series, trying to figure out why we're not all jumping for joy if Tov Hashem l'kol , God is good to everybody. Why is it that most people don't realize it? And we gave two reasons. Reason number one is we're always looking for more. Reason number two, we're just used to it. And reason number three, because things don't always go right. And we have financial losses, we have physical ailments and we don't understand how these can possibly be good for us. We don't get the benefit of nisayon , tests. We don't have the benefits of musar . That means anything that goes wrong in our life is for one of two reasons: it's a test, means we didn't do anything wrong, Hashem's testing us, or it's for musar purposes to give us rebuke, to change. And he quotes a pasuk in Tehillim , Ashrei ha'gever , fortunate is the man, asher t'yasrenu Kah , that God rebukes him, u'mTorascha tolamdenu , and he learns from the Torah, which means he gets the message. And we forget that we and everything that we have are nothing more than gifts of God. That's all we are. Our existence and everything we have are all gifts of God. Generous, kind gifts. And everything that he gives us is b'tzedek . Everything he gives us is done with a just approach based on what God's wisdom feels is right. And we are not accepting of that justice. And not only do we not praise him when God reveals his kindness on us, we actually deny the good to begin with. And he says that this denial is rooted in foolishness. And it comes to the point that people think that they could be smarter than God in how they run the world and how they make things happen. And this is a famous, great Chassidic Rebbe that they asked him the question, if you were God, how would you run the world? If you could change things, what would you do? If you ask people around the table now, someone would say, well, I would find the new mayor for New York, or I would stop the terrorist attacks in Israel, or whatever else I would do. I would heal all the sick. I would get matches for all those without shidduchim and cure all mental health illnesses in the world. And the Rabbi answered, I wouldn't do anything any different than's going on right now because God knows exactly what he's doing and I don't think I could do anything better than he can. And it's really, in a sense, it's a sense of arrogance where we think, well, we could do better. We have better ideas for how to run the world than God does. And he gives a mashal of a group of blind people that were brought into a hospital, a center that was made specifically for them and all their needs. And every possible machine was there, every possible comfort was there, perfectly made for them, rails that they could hold on to when they walk, blinking, you know, beeping noises that they know what if things are safe or unsafe, all types of medicines and pharmacies and doctors. And they didn't pay attention to any of the rules, any of the regulations, didn't follow any doctor's instructions. And they walked through the hospital without listening to the beeps. They tripped, they fell, they banged into the machine that was there to fix them. They broke their arms, they were in pain, they were crying. And they said, who built this place? It's a disaster. We're falling all over the place. He doesn't know what he's doing. He's not a good doctor. He doesn't know how to run anything. And they don't realize that everything here was set up for kindness and goodness, not to paint anybody. And if anything, the one that caused the pain was the person themselves. And they now go deny the benefit and the goodness of the one that helped them. And he quotes a pasuk in Kohelet to this effect. The path that the fool takes is without heart and he announces to the world that he's a fool. Which means that's the person that goes through this world in a foolish way, and by denying God, announces to the world that he's foolish. So that's the first important premise in appreciating our lives is to understand that there's a lot of things that we're not gonna understand. I once heard a beautiful line, I don't know who said it. that the difference between the atheist and the believer. The believer has one thing to deal with. They don't understand why righteous people suffer. That's the question that Moshe Rabbeinu asked. That's the one thing that believing people don't understand. Atheists? They don't understand where a flower came from, where an eye came from, where a heart came from, where the Swiss Alps came from, where air came from. They don't understand anything. We have one thing. We don't understand exactly how God deals with us. Okay. Well, if anything, as we'll see later on, the very fact that we see such wonders of creation tells us how smart and understanding God is. And therefore, we'll tell ourselves, if we don't understand how to create a embryo, we don't know how to make a fly, well, shows God pretty smart. And if he could make a fly, he could probably

On Transience and the Cycle of Time: Freud and Ecclesiastes with Paul Marcus, PhD (Great Neck, New York)

"The similarity between Freud and Kohelet [Ecclesiastes] is that both of them believe that there's no overarching totalistic system that integrates all the disparate experiences that one has. You have that, Freud says, in psychotics, and you have that in philosophers, and you have that in devout people - they look for systematicity. They try to cram everything into a framework of meaning. Both Freud and Kohelet reject that. They don't have a worldview in that way. However, in order to flourish, you do need a meaning-giving, affect-integrating and action-guiding set of considerations. You can't just be out there like a windowless monad floating around. There are some core beliefs and values that anchor a person, that give them footing. So there's a difference between a totalizing worldview and a workable framework that's open to critique." Episode Description: We begin with a brief reading from On Transience and Ecclesiastes and consider how they both belong to 'Wisdom Literature' while separated by over 2000 years. Paul points out that while Freud works from a linear sense of time, Ecclesiastes (Kohelet) is drawn to the cycles of nature and human experience. He provides clinical examples that he feels are enriched by considering the teachings of Ecclesiastes which are very similar to the psychoanalytic way of thinking - "one must learn to live with what cannot be altered," the importance of the "downsizing of infantile narcissism," and recognizing that "pleasure and joy are palpable, sensual and concrete experiences." We discuss the importance of an object-related life that includes forgiveness and gratitude as well as "embracing resignation without despair." We conclude with the deeply moving time poem "To every thing there is a season/ and a time to every purpose under heaven..." Our Guest: Paul Marcus, PhD is a training and supervising analyst at the National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis in New York and Co-chair of the discussion group Psychoanalysis and Spirituality in the American Psychoanalytic Association. He is the author/editor of 25 books including The Spiritual Resistance of Rabbi Leo Baeck: Psychoanalysis and Religion. He is the editor of Psychoanalytic Review. Recommended Readings: Seow, C.L. 1997, Ecclesiastes: A New Translation. New Haven: Yale University Press Fox, M. V., 2004, Ecclesiastes, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society Heim, K.M., 2019, Ecclesiastes, Downers Grove: IVP Academic

This series is sponsored by American Security Foundation.In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast—recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit—we speak with Moshe Koppel, Malka Simkovich, and Tikvah Wiener about what the AI revolution will mean for the Jewish community.In this episode we discuss:How is AI going to change the dynamics, cadence, and rhythm of Jewish life? Should we panic about AI replacing the role of creative human work? What can Jewish and world history teach us about this moment? Tune in to hear a conversation about what AI can teach us about our own needs, especially the need for Shabbos. Interview begins at 14:26.Dr. Moshe Koppel is a computer scientist, Talmud scholar, and political activist. Moshe is a professor of computer science at Bar-Ilan University, and a prolific author of academic articles and books on Jewish thought, computer science, economics, political science, and other disciplines. He is the founding director of Kohelet, a conservative-libertarian think tank in Israel, and he advises members of the Knesset on legislative matters. Dr. Malka Simkovich is the director and editor-in-chief of the Jewish Publication Society and previously served as the Crown-Ryan Chair of Jewish Studies and Director of the Catholic-Jewish Studies program at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. She earned a doctoral degree in Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism from Brandeis University and a Master's degree in Hebrew Bible from Harvard University. Tikvah Wiener is Founder and Co-Director of The Idea Institute, which, since 2014, has trained close to 2000 educators in project-based learning and innovative pedagogies. From 2018-2023, she was also Head of School of The Idea School, a Jewish, project-based learning high school in Tenafly, NJ.References:“Lazy Sunday - SNL Digital Short”Mechkarim Be-sifrut Ha-teshuvot by Yitzchak Ze'ev Kahane"In the Shadow of the Emperor: The Hatam Sofer's Copyright Rulings" by David NimmerMeta-Halakhah: Logic, Intuition, and the Unfolding of Jewish Law by Moshe KoppelJudaism Straight Up by Moshe Koppel“Yiddishkeit Without Ideology: A Letter To My Son” by Moshe Koppel@ShabbosReadsFor more18Forty:NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/joinCALL: (212) 582-1840EMAIL: info@18forty.orgWEBSITE: 18forty.orgIG: @18fortyX: @18_fortyWhatsApp: join hereBecome a supporter of this podcast: https://www.spreaker.com/podcast/18forty-podcast--4344730/support.

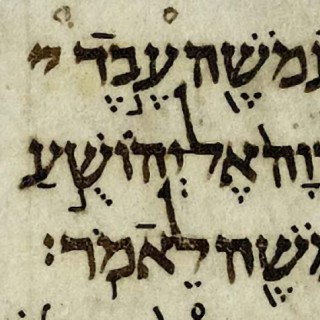

A mistake for mincha and two things to watch out for in Kohelet. Follow along in Devarim 34:11, 34:1, Kohelet 3:11, 5:16, 2:23, Bereshit 1:2. Provide your feedback or join the WhatsApp group by sending an email to torahreadingpodcast@gmail.com.

#557 - Shabbat Chol HaMoed Sukkot - Keep the Main Thing the Main Thing

Metzudat David suggests that Kohelet is doing more than observing.

The Neshamaha Project: Episode 91- All Is Breath: The Maor VaShemesh on Kohelet

In this episode of The Neshamah Project, we explore two luminous teachings from the Maor VaShemesh on Kohelet. First, “All is breath” — a vision of life as sacred exhalation, where every word and action flows from divine intention. Second, “The breath of many voices” — a reminder that when we gather in prayer, song, or silence, our shared breath reshapes the world. Together, these teachings invite us to return to simplicity, to presence, and to the living rhythm that connects every soul.

Moshe Koppel: Artificial Intelligence and Torah [Prayer Re-Release]

As a hint at our next new series, we want to share with you our 2023 episode with Moshe Koppel—a computer scientist and Talmud scholar—about Torah and its intersection with artificial intelligence.In a world in which technology puts vast libraries of Torah at our fingertips, we are tasked with thinking more deeply about what essentially human abilities we bring to the enterprise of Torah and tefillah. In this episode we discuss:What computer-based innovations are on the horizon in the realm of Torah study?Will AI ever be able to reliably answer our halachic questions?Will advances in technology drastically change the experience of Shabbos observance?Tune in to hear a conversation about how AI has the potential to make our Jewish lives richer—if we use it wisely.Interview begins at 18:21.Dr. Moshe Koppel is a computer scientist, Talmud scholar, and political activist. Moshe is a professor of computer science at Bar-Ilan University, and a prolific author of academic articles and books on Jewish thought, computer science, economics, political science, and other disciplines. He is the founding director of Kohelet, a conservative-libertarian think tank in Israel, and he advises members of the Knesset on legislative matters. Dr. Koppel is the author of three sharply thought books on Jewish thought and previously joined 18Forty to talk about Halacha as Language.References:“Funes the Memorious” by Jorge Luis BorgesThe Mind of a Mnemonist by A.R. LuriaSurfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking by Douglas R. Hofstadter & Emmanuel SanderGödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas R. HofstadterMeta-Halakhah: Logic, Intuition, and the Unfolding of Jewish Law by Moshe Koppel2001: A Space OdysseyDICTA: Analytical tools for Hebrew texts“Digital Discourse and the Democratization of Jewish Learning” by Zev EleffTzidkat HaTzadik: 211 by Tzadok HaKohen of LublinBecome a supporter of this podcast: https://www.spreaker.com/podcast/18forty-podcast--4344730/support.

Benjamin J. Segal, "Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes" (Gefen, 2016)

The Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes—full of poetry and enigmatic imagery, these are among the most challenging books of the Bible to understand. Well take heart, because we have some help coming your way! Tune in as we speak with Rabbi Benjamin Segal about his Gefen publications on the Ketuvim. We'll talk with Rabbi Segal about his translations and commentaries on: Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes, and The Song of Songs: A Woman in Love, and finally also Lamentations: Doorways to Darkness. Rabbi Benjamin Segal is former president of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, has authored many commentaries, other books and articles. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/biblical-studies

Benjamin J. Segal, "Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes" (Gefen, 2016)

The Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes—full of poetry and enigmatic imagery, these are among the most challenging books of the Bible to understand. Well take heart, because we have some help coming your way! Tune in as we speak with Rabbi Benjamin Segal about his Gefen publications on the Ketuvim. We'll talk with Rabbi Segal about his translations and commentaries on: Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes, and The Song of Songs: A Woman in Love, and finally also Lamentations: Doorways to Darkness. Rabbi Benjamin Segal is former president of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, has authored many commentaries, other books and articles. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/new-books-network

Benjamin J. Segal, "Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes" (Gefen, 2016)

The Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes—full of poetry and enigmatic imagery, these are among the most challenging books of the Bible to understand. Well take heart, because we have some help coming your way! Tune in as we speak with Rabbi Benjamin Segal about his Gefen publications on the Ketuvim. We'll talk with Rabbi Segal about his translations and commentaries on: Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes, and The Song of Songs: A Woman in Love, and finally also Lamentations: Doorways to Darkness. Rabbi Benjamin Segal is former president of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, has authored many commentaries, other books and articles. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/jewish-studies

Benjamin J. Segal, "Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes" (Gefen, 2016)

The Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes—full of poetry and enigmatic imagery, these are among the most challenging books of the Bible to understand. Well take heart, because we have some help coming your way! Tune in as we speak with Rabbi Benjamin Segal about his Gefen publications on the Ketuvim. We'll talk with Rabbi Segal about his translations and commentaries on: Kohelet's Pursuit of Truth: A New Reading of Ecclesiastes, and The Song of Songs: A Woman in Love, and finally also Lamentations: Doorways to Darkness. Rabbi Benjamin Segal is former president of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, has authored many commentaries, other books and articles. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/christian-studies

Remember during the boom times to use it well, because the times of bust are coming. In the end, there is purpose to it all.

Spread goodness without restriction, because what goes around, comes around. Don't keep waiting for the right moment to do something good, as no moment is better than right now.

A fool talks and talks and pretends to know things that cannot be known, while a wise man understands his limitations. Choose leaders who know what they can and cannot do and say.

Refraining From Meat and Wine During the Nine Days

Daily Halacha Podcast - Daily Halacha By Rabbi Eli J. Mansour

The Mishna in Masechet Ta'anit (26b) states that one may not eat meat or drink wine during the final meal before Tisha B'Ab. This is the only restriction on the consumption of meat mentioned by the Mishna or Gemara. On the level of strict Halacha, one is permitted to eat meat during the days preceding Tisha B'Ab, and even on the day before Tisha B'Ab, except during the last meal before the fast. However, customs were accepted among many Jewish communities to abstain from meat already earlier. The Shulhan Aruch (Orah Haim 551:9) brings three customs. Some refrain from eating meat already from after Shabbat Hazon (the Shabbat immediately preceding Tisha B'Ab); others observe this restriction throughout the Nine Days; and others follow the practice not to eat meat throughout the entire three-week from Shiba Asar Be'Tammuz through Tisha B'Ab. The Shulhan Aruch writes that everyone should follow his community's custom. Of course, this prohibition applies only on weekdays. According to all customs, one may eat meat on Shabbat, even the Shabbat before Tisha B'Ab. These customs developed for two reasons: 1) as part of our obligation to reduce our joy during this period when we are to reflect upon the destruction of the Bet Ha'mikdash; 2) the destruction of the Bet Ha'mikdash resulted in the discontinuation of the offering of sacrifices, such that G-d no longer has meat, as it were, so we, too, should not enjoy meat. The Gemara (Baba Batra 60b) states that there were those who, after the destruction of the Bet Ha'mikdash, decided to abstain from meat and wine, since there were no longer animal sacrifices or wine libations offered to G-d. However, they were told that by this logic, they should also refrain from grain products, because flour offerings (Menahot) could no longer be offered, and even from water, because the water libations (Nisuch Ha'mayim) were no longer offered. Quite obviously, we cannot live this way, and so we are not required to abstain from those products which were offered in the Bet Ha'mikdash. Nevertheless, as part of our effort to focus our attention on the tragedy of the Hurban (destruction) in the period leading to Tisha B'Ab, the custom developed to refrain from meat. Notably, not all communities accepted these restrictions. The Maggid Mishneh (Rav Vidal of Tolosa, Spain, late 14 th century) writes that in his area, the custom was to permit meat except on Ereb Tisha B'Ab. The Meiri (Provence, 1249-1315) writes that there was a practice among the exceptionally pious to refrain from meat on Ereb Tisha B'Ab, but even they did not refrain from meat before that day. Regardless, the Shulhan Aruch emphasizes that people whose communities observe the custom to refrain from meat during this period must adhere to the custom. Those who violate this practice are included in King Shlomo's stern warning in Kohelet (10:8), "U'foretz Geder Yishechehu Nahash" – "He who breaches a fence, a snake shall bite him." Even if a restriction that applies on the level of custom, and not as strict Halacha, is binding and must be obeyed. Nevertheless, since refraining from meat is required only by force of custom, there is greater room for leniency than there is when dealing with strict Halachic prohibitions. Thus, it has become accepted to permit meat when a Siyum celebration is held, and one should not ridicule those who rely on this leniency. In fact, it is told that Rav Moshe Feinstein (1895-1986) would conduct a Siyum every night during the Nine Days in the place where he would spend his summers, so that the people could eat meat. Since the prohibition to begin with is observed by force of custom, and not on the level of strict Halacha, the leniency of a Siyum is perfectly legitimate. In practice, when should we begin abstaining from meat? The accepted custom in our Syrian community is to begin refraining from eating meat from the second day of Ab. Although different opinions exist regarding the consumption of meat on Rosh Hodesh Ab, our custom follows the view of the Hida (Rav Haim Yosef David Azulai, 1724-1806) permitting the consumption of meat on this day. This was also the custom in Baghdad, as mentioned by the Ben Ish Hai (Rav Yosef Haim of Baghdad, 1833-1909), and this is the generally accepted custom among Sepharadim. One who does not know his family's custom can follow this practice and begin refraining from meat on the second day of Ab. The Kaf Ha'haim (Rav Yaakov Haim Sofer, Baghdad-Jerusalem, 1870-1939) cites an earlier source (Seder Ha'yom) as ruling that Torah scholars should follow the stringent practice of abstaining from meat already from Shiba Asar Be'Tammuz. However, recent Poskim – including Hacham Ovadia Yosef – ruled that since nowadays people are frailer than in the past, and Torah scholars need strength to continue their studies and their teaching, they should not observe this stringency. They should instead follow the more common custom to refrain from meat only after Rosh Hodesh Ab. One who wishes to eat a meat meal late in the day on Rosh Hodesh Ab should ensure not to recite Arbit early, before sundown. Once he recites Arbit, he in effect ends Rosh Hodesh, and begins the second day of Ab when eating meat is forbidden. One who wishes to recite Arbit early on Rosh Hodesh Ab must ensure to finish eating meat beforehand. The custom among the Yemenite Jewish community was to follow the Mishna's ruling, and permit eating meat except during the final meal before Tisha B'Ab. However, Hacham Ovadia Yosef ruled that once the Yemenites emigrated to Eretz Yisrael, they should follow the rulings of the Shulhan Aruch, and abstain from meat during the Nine Days. This prohibition applies even to meat that is not fresh, such as it if was canned or frozen. The Nehar Misrayim (Rav Aharon Ben Shimon, 1847-1928) records the custom among the Jewish community in Egypt to permit eating chicken during the Nine Days. As mentioned earlier, one of the reasons for the practice to refrain from meat is that we commemorate the loss of sacrificial meat in the Bet Ha'mikdash. Accordingly, Egyptian Jews permitted eating chicken, as chickens were not brought as sacrifices. This is the custom among Jews of Egyptian background even today. The Shulhan Aruch (551:10), however, explicitly includes chicken in his formulation of the custom to refrain from meat during the Nine Days. The Mishna Berura writes that one who is unable to eat dairy products (such as if he suffers from a milk allergy), and thus has limited options for food during the Nine Days, may eat chicken. If one needs to eat meat for health reasons, he should preferably eat chicken instead of beef, as there is greater room for leniency when it comes to chicken. Hacham Ovadia Yosef writes that if one removed the meat from a dish that consisted also of other food – such as if the meatballs were removed from the spaghetti – then, strictly speaking, the remaining food is permissible. Nevertheless, it is customary to be stringent in this regard and refrain from eating food which had been cooked together with meat. If parve food was prepared in a meat pot, the food may be eaten during the Nine Days, since it does not have meat in it. Even if the pot had been used with meat less than 24 hours before it was used to cook the parve food, the parve food may be eaten. This food contains the taste of meat, but not actual meat, and it is thus entirely permissible during the Nine Days. (In fact, according to the ruling of the Shulhan Aruch, this parve food may be eaten together with milk or yoghurt. The meat taste in this food has the status of "Noten Ta'am Bar Noten Ta'am" – a "second degree" taste, as the pot absorbed the taste of the meat, and the parve food then absorbed the taste from the pot. At this point, the taste does not forbid the food from being eaten with milk.) Hacham Ovadia Yosef allowed eating soup from bouillon cubes or bouillon powder during the Nine Days. It is permissible to eat fish during the Nine Days, though some have the custom not to eat fish during the final meal before Tisha B'Ab. One is allowed to eat synthetic meat during the Nine Days. Although one might have thought that this should be avoided due to the concern of Mar'it Ha'ayin – meaning, a person eating synthetic meat might be suspected of eating actual meat – we do not have the authority nowadays to enact new prohibitions out of this concern. If a person forgot that it was the Nine Days, or forgot about the restriction against eating meat, and he recited a Beracha over meat but then remembered that it is forbidden, he should take a bite of the meat, because otherwise his Beracha will have been recited in vain, in violation of the severe prohibition of Beracha Le'batala (reciting a blessing in vain). This is a far more grievous transgression than partaking of meat during the Nine Days – which, as we explained, is forbidden only by force of custom – and it is therefore preferable to take a bite of the meat so that the blessing will not have been recited in vain. (This resembles the case of a person who prepared to eat a dairy food within six hours of eating meat, and remembered after reciting the Beracha that he may not eat the dairy food. In that case, too, he should take a bite of the dairy food so the Beracha will not have been recited in vain. This applies also to someone who recited a Beracha to eat before praying in the morning, and then remembered that he may not eat because he had yet to pray. Even on fast days – except Yom Kippur, when eating is forbidden on the level of Torah law – if someone recited a Beracha over food and then remembered that eating is forbidden, he should take a small bite of the food.) If a person owns a meat restaurant, he is permitted to operate the restaurant during Nine Days, even in a Jewish community, where most or all of his customers are Jews. Given the leniencies that apply, such as permitting meat at a Siyum, and when necessary for health reasons, it is not for certain that the people coming to eat will be violating the custom to refrain from meat. As such, operating the restaurant does not violate the prohibition against causing people to sin. However, it is proper for the restaurant owner to place a visible sign at the entrance to the restaurant informing people of the widely-accepted custom to refrain from eating meat during the Nine Days. Just as many observe the custom to refrain from meat during the Nine Days, it is also customary to refrain from wine during this period. Although the practice in Jerusalem was to be lenient in this regard, and drink wine during the Nine Days, the practice among other Sephardic communities is to refrain from wine. This was also the custom in Arab Soba (Aleppo), as documented in the work Derech Eretz, and this is the practice in our community. There are two reasons for this custom. First, wine brings a feeling of joy, and during the month of Ab, until Tisha B'Ab, we are to reduce our joy and reflect on the destruction of the Bet Ha'mikdash. Secondly, we refrain from wine because we can no longer pour wine libations on the altar. Of course, wine – like meat – is permissible on Shabbat during the Nine Days. The restriction applies only on weekdays. It is permissible to drink other alcoholic beverages during the Nine Days, such as beer and whiskey. Cognac, however, is a type of wine, and is therefore forbidden. One should not drink grape juice during the Nine Days, but grape soda is allowed. Cakes that are baked with grape juice instead of water are allowed during the Nine Days unless the taste of grape juice is discernible, in which case one should refrain from these cakes. Vinegar made from wine is permitted for consumption during the Nine Days, because it has an acidic taste and does not bring enjoyment. Similarly, juice extracted from unripe, prematurely-harvested grapes is permissible. The Shulhan Aruch allows drinking wine at Habdala on Mosa'eh Shabbat during the Nine Days. The Rama (Rav Moshe Isserles, Cracow, 1530-1572), however, writes that according to Ashkenazic custom, the Habdala wine is given to a child to drink. The Shulhan Aruch also writes that one may drink during the Nine Days the cup of wine over which Birkat Ha'mazon is recited. When three or more men ate together, and they recite Birkat Ha'mazon with the introductory Zimun, it is customary for the one who leads the Zimun to hold a cup of wine during Birkat Ha'mazon which he then drinks after Birkat Ha'mazon, and according to the Shulhan Aruch, this cup may be drunk during the Nine Days. However, Hacham Ovadia Yosef rules that since nowadays people generally do not make a point of reciting Birkat Ha'mazon over a cup of wine, this is not permitted during the Nine Days.

It is not the powerful who win wars, but the wise.

Don't waste your emotional energy trying to understand God's ways. just appreciate what you have and enjoy it.

Kohelet teaches us to take the middle path, too much in either direction leads down to a destructive path.

Every Moment Counts

The pasuk in Kohelet says: " עֵת לָלֶדֶת וְעֵת לָמוּת " — "A time to be born, and a time to die." (Kohelet 3:2). The Midrash in Kohelet Rabbah teaches that from the moment a person is born, Hashem determines exactly how long that person will live. Every breath, every second, is measured. And it is considered a great merit for someone to live out every single moment of their allotted time in this world. We cannot begin to grasp the infinite value of just one second of life. Sometimes, patients who are suffering deeply may wish to pass on rather than continue living in pain, connected to machines. Their families, too, may struggle watching them suffer. These situations are deeply painful and emotionally charged—but they are also halachically complex, and a competent Rav must always be consulted. These are not decisions anyone should take into their own hands. Halachah teaches us that we desecrate Shabbat to extend the life of a patient even in a vegetable state, even if it's just for one more second. That is how precious life is in Hashem's eyes. Rabbi Aryeh Levin once visited a man who was suffering terribly in the hospital. The man asked the rabbi, "Why should I continue living like this? I can't pray, I can't learn. I'm just in pain." Rabbi Levin gently took his hand and answered, "Who knows? Perhaps one word of Shema said in pain is worth more than a lifetime of mitzvot done in comfort. Every breath you take now—with emunah—brings Hashem so much nachat." The man began to cry. From that moment on, he accepted each breath with emunah and gratitude. He passed away just a few days later—peaceful, uplifted, and surrounded by meaning. Chazal say: "Sha'ah achat shel teshuvah u'maasim tovim ba'olam hazeh yafeh mikol chayei ha'olam haba"—one hour of repentance and good deeds in this world is greater than all of the World to Come. In just one moment, a person can elevate himself spiritually forever. The Gemara in Avodah Zarah shares three separate stories of individuals who earned their entire portion in the World to Come in one moment of their life. When Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi heard them, he wept, recognizing the unimaginable power of even a single second. The Sifrei Kodesh teach that even one thought of teshuvah can have massive spiritual effects. Even a person on his deathbed, who cannot speak or move, can—through one pure thought, one yearning for Hashem—accomplish more than all the angels in Heaven combined. If all a person can do is breathe, that breath is a treasure beyond comprehension. As long as someone is breathing, Hashem wants him alive. His mission in this world is not yet complete. A man shared with me that his father, Eddie, recently passed away. He had told his children that if he reached the end of life, he didn't want to be kept alive artificially and in pain. But when the time came, his children called Chayim Aruchim, an organization that helps families navigate end-of-life issues according to halachah. They were given a personal Rav who was an expert in this field. He came down to the hospital and explained the halachic importance—and the spiritual benefit to Eddie and his family—of staying connected to the machine, even for a short time. The Rav monitored his condition every day for ten days, ensuring halachah was followed precisely. Eventually, the doctors said Eddie's final moments had come. His children gathered around his bed and watched their father take his last breaths. They were so grateful they had consulted daat Torah and allowed their father to live every moment Hashem had intended for him. And then, just as they left the hospital, a truck drove by with the word "Eddie's" written in big letters—something they had never seen before. To them, it felt like a wink from Hashem, a small smile from Above, affirming that they had done the right thing. Every second of life is a priceless gift. In one moment, a person can earn eternity. And sometimes, the last breath we breathe with emunah is something that brings the greatest glory to Hashem.

It is all about the present, but that is a reason to value the present and use it right. It is not the time to waste the opportunity to live properly.

Episode 650 Revelation and Resistance: Praising God in the Midst of Empire (Revelation 7:1-17)

This week we are reading Revelation chapter 7, a vision that unfolds in the midst of the unsealing of seals and undoing of worlds as we have known them. It's a vision that seems anchored in the past and the future simultaneously, a vision that evoked for us Ezekiel and Isaiah and Genesis and Kohelet and Exodus and also a also future time when whatever suffering the faithful have endured, they can stand together in their multitudes and praise the one true Source. It's an image that, at the very least, can make the work of our time less lonely.

Who knows what will happen tomorrow? Let in the sunlight today!

Kohelet 5b - Enjoy it Now Because It Won't Last long

Better to enjoy the fruits of your labor while you have it, because we all leave the world the same as we entered it.

Kohelet 4b & 5a - God is in Heaven, We Are on Earth

Kohelet reminds us that we will never understand God and thus challenging Him is a waste of time. Instead we should focus on our lives, keep our promises, and be smart about our actions.

Kohelet advises us that despite the seeming futility of our efforts, we should still not fold our hands and do nothing. However we should choose something meaningful, with purpose and together with others.

There is a time and season for everything, we must enjoy and experience each moment, and live properly each moment of our lives.

We don't understand the ways of God, but it is better to be wise than to be foolish, and it is important to enjoy the momentary pleasures that we are privileged to experience.

How does Kohelet end?What is his conclusion?Does he concluded with a soliloquy about death, or a series of statements about guidance and life?

Practice kindness, diversify your investments, invest in life - even if you cannot fully understand it, and enjoy your youth! These are Kohelet's messages - a philosophy of humble pragmatism.

Kohelet ch.10 - Wisdom, Foolishness; and the Fly in the Ointment

One act of foolishness can sully a sterling reputation.

Death might be the great equalizer, but in the meantime, there are better ways to live and worse ways.

How might we act in the face of temperamental but powerful figures of government?How do we navigate an unpredictable world in which good and bad are seldom evident?Do we just eat and drink and be happy? Or maybe we allow wisdom to make our face shine.

The word "tov -good" is the keyword of our chapter.Kohelet has been asking what the key to good is. In this chapter he offers a new pragmatic approach.

6:9: "Better what you can see than the wanderings of desire."Today we address the attractions and fantasies that make us not only dissatisfied with our worldly blessings but also sap our ability and focus to appreciate and be present in the good fortune that we experience.

This world can be tough. Kohelet suggests that many people might prefer never to have been born at all.And yet, with a little financial modesty and less comparison, with some simple companionship, we will see success and happiness.

Kohelet ch.5 - Musings about Religion, Action and Speech

Is there a value in visiting the Temple?Should an individual make a vow?The opening lines of chapter 5 speak about religious ritual, the power of speech and the manner in which a person approaches God. What is Kohelet's perspective?

A time to give birth and a time to die; a time to plant and a time to uproot that which is planted... A time to love and a time to hate; a time for war and a time for peace.

Kohelet entertains three possibilities of what might make life meaningful: wisdom, pleasure and work. But the ultimate litmus test will be the death of a person; does anything valuable endure after we depart this work. Is everything ephemeral (hevel)?

What is the meaning of life? That is essentially the question that Kohelet seeks to address.Who is Kohelet?What does he mean when he says: "All the rivers flow into the sea but the sea is never full"?

A conversation about the lessons we can learn from Megillas Esther for our current times, walking through the doorways G-d calls us to, navigating responsibilities that we didn't sign up for, the synthesis of modern wisdom with Torah, differentiating between the sacred and unsacred, and how to begin developing a relationship with Torah study. Dr. Erica Brown is the Vice Provost for Values and Leadership at Yeshiva University and the founding director of its Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks-Herenstein Center for Values and Leadership. She previously served as the director of the Mayberg Center for Jewish Education and Leadership and an associate professor of curriculum and pedagogy at The George Washington University. Erica is the author or co-author of 15 books on leadership, the Hebrew Bible and spirituality. Erica has a daily podcast, “Take Your Soul to Work.” Her book Esther: Power, Fate and Fragility in Exile (Maggid) was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. Her latest book is Kohelet and the Search for Meaning (Maggid). She and her husband live in Maryland and have four children, another four through marriage, and six exquisite grandchildren. Explore more of her work at ericabrown.com.Video episode is available on Youtube. To inquire about sponsorship & advertising opportunities, please email us at info@humanandholy.comTo support our work, visit humanandholy.com/sponsor.Find us on Instagram @humanandholy & subscribe to our channel to stay up to date on all our upcoming conversations. Human & Holy podcast is available on all podcast streaming platforms. New episodes every Sunday on Youtube, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts.Timestamps:0:00 Introduction2:50 Welcome Dr. Erica Brown 4:43 What We Can Learn from Megillas Esther 10:10 How Can We Show Up Right Now?12:58 A Relationship with G-d is Dynamic15:10 Harnessing the Jewish Shift in the Diaspora 18:00 The Power of Invitation19:00 Developing a Personal Interest in Tanach21:58 Bringing the Totality of Ourselves to the Text23:10 The Story of Jonah: The Wishful Fantasy of Adulthood24:45 When Your Responsibilities Feel Like Too Much 27:58 Getting Guidance From Those Who Have Walked the Path20:55 When You Didn't Sign Up for What Life is Asking of You33:50 Asking for Help: Esther and Mordechai's Partnership 35:05 The Mezuzah: Walking Through the Doorway With G-d37:50 Bringing All Worlds of Wisdom to the Torah 40:50 Filtering Out the Unholy43:20 Will AI Change the Way We Study Torah?47:10 Advice on Developing a Relationship with Torah Study