Podcasts about if i didn

- 22PODCASTS

- 33EPISODES

- 49mAVG DURATION

- 1MONTHLY NEW EPISODE

- Jul 28, 2021LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about if i didn

Latest podcast episodes about if i didn

Jason Aldean, Carrie Underwood, "If I Didn't Love You" [TRASH OR FIRE?] [REVIEW!]

Jason Aldean, Carrie Underwood, "If I Didn't Love You" [TRASH OR FIRE?] [REVIEW!] TAGS: jason aldean and carrie underwood, jason aldean heaven, jason aldean got what i got, jason aldean songs, jason aldean new song, jason aldean rearview town, jason aldean you make it easy, jason aldean fly over states, jason aldean amarillo sky, jason aldean asphalt cowboy, jason aldean album, jason aldean any ol barstool, jason aldean and bob seger, jason aldean acoustic, jason aldean and bryan adams, jason aldean blame it on you, jason aldean big green tractor, jason aldean burnin it down, jason aldean bob seger, jason aldean blame it on the whiskey, jason aldean black tears, jason aldean barstool, jason aldean blame it on you lyrics, jason aldean b, jason aldean carrie underwood, jason aldean cowboy lady,jason aldean country girl,jason aldean concert,jason aldean crazy town,jason aldean cowboy killer,jason aldean camouflage hat,jason aldean cover,jason aldean dirt road anthem,jason aldean drowns the whiskey,jason aldean dirt road,jason aldean don't give up on me,jason aldean do you wish it was me,jason aldean don't you wanna stay,jason aldean dirt we were raised on,jason aldean dirt road anthem lyrics,jason aldean easy,jason aldean even if i wanted to,jason aldean even if i wanted to lyrics,jason aldean eric church,jason aldean early songs,jason aldean ellen,jason aldean eric church luke bryan,jason aldean easy lyrics,kelly clarkson e jason aldean,bryan adams e jason aldean,jason aldean full album,jason aldean fast,jason aldean first album,jason aldean ft carrie underwood,jason aldean first time again,jason aldean fly over states live,jason aldean full throttle,jason aldean girl like you,jason aldean greatest hits,jason aldean got what i got lyrics,jason aldean gonna know we were here,jason aldean green tractor,jason aldean girl like you lyrics,jason aldean got what i got live,jason aldean g,jason aldean hicktown,jason aldean hits,jason aldean heaven lyrics,jason aldean heaven cover,jason aldean high noon neon,jason aldean hicktown live,jason aldean highway,jason aldean if i didn't love you,jason aldean i got what i got,jason aldean i don't drink anymore,jason aldean interview,jason aldean i ain't ready to quit,jason aldean if my truck could talk,jason aldean if i didn't love you lyrics,jason aldean i'll wait for you,i don't jason aldean,i do jason aldean,jason aldean johnny cash,jason aldean just getting started,jason aldean joe diffie,jason aldean jimmy kimmel,jason aldean just passing through,jason aldean just a man,jason aldean just getting warmed up,jason aldean jason aldean,jason aldean karaoke,jason aldean kelly clarkson,jason aldean keep the girl,jason aldean know we were here,jason aldean keeping it small town,jason aldean kelly clarkson don't you want to stay,jason aldean king ranch,jason aldean karaoke songs,jason aldean live,jason aldean lyrics,jason aldean lights come on,jason aldean love me or don't,jason aldean las vegas,jason aldean laughed until we cried,jason aldean love songs,jason aldean las vegas shooting,jason aldean l,jason aldean my kinda party,jason aldean mix,jason aldean music,jason aldean make it easy,jason aldean my kinda party album,jason aldean music videos,jason aldean midnight train,jason aldean my highway,jason aldean 3 a.m,jason aldean night train,jason aldean new,jason aldean new album,jason aldean night train album,jason aldean never met a girl like you,jason aldean night train lyrics,jason aldean no,jason n aldean,jason aldean guns n roses,jason aldean old songs,jason aldean old boots new dirt,jason aldean only way i know,jason aldean on my highway,jason aldean old boots new dirt full album,jason aldean once in your life,jason aldean over states,jason aldean on las vegas,jason aldean playlist,jason aldean party,jason aldean pretty cowboy lady,jason aldean playlist all songs,jason aldean passing through,jason aldean perfect for me,jason aldean prisoner of the highway,jason aldean performance,jason

JJ's Conversation with Jason Aldean about The New Single, Quarantine and More | JJ Hayes | KFDI

It's Jason Aldean Day as we celebrate the release of his new single "If I Didn't Love You". It's a duet with Carrie Underwood, but that was never a guarantee. Check out the interview to hear how it happened, what his go-to at Chick Fil-A is, The waterslide and more.

Get ready for a scare this week as Ken and Gar review Pixar's 4th animated feature, Monsters, Inc. first released in 2001. The brother's unpack why Pete Docter's directorial debut is one of the most interesting and challenging animated films of its time. Featuring a cover "If I Didn't Have You" from Monsters, Inc. by Magic by Design's resident singer, Nicole McDonagh. We hereby declare that we do not own the rights to this music/song(s). All rights belong to the owner. No copyright infringement intended.Follow Nicole @NicoleMcD_PR on Twitter and @n.mcdonagh on Instagram for more magical musical contentWatch along on Disney Plus and join the conversation on social media:Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MagicByDesignPodTwitter: @MagicDesignPodInstagram: @magicbydesignpod

Today's Best & your All Time Favorites From the US, Texas & Canada 1st for Weekly neo-traditonal & classic Country program Fred's Country 2021 w # 26 : Part 1: - Josh Turner, Your Man (Live in Kansas City, MO) - Your Man Deluxe - 2021/MCA - Casey Donahew, Queen For A Night - S – 2021/Almost Country - Ben McPeak, Fix You Up - Better Off – 2020/396 Entertainment - Bellamy Brothers feat John Anderson, No Country Music For Old Man - Bucket List – 2020/BBR Part 2: - Creed Fisher, People Like Me - S – 2021/JHM - Mike Ryan, Can Down - S – 2020/MRM - Chad Cooke Band, Señorita Sky - S – 2021/CCB - Jon Pardi, Tequila Little Time - Heartache Medication Deluxe - 2019/Capitol - Travis Tritt, Country Club - Country Club – 1990/Warner Part 3: - Thomas Rhett, Country Again - Country Again – 2021/Valory - Gord Bamford, Hag on the Jukebox - Diamonds in a Whiskey - 2021/Black Mountain Music & Media - Jake Bush, If You Ever Get Lonely - 7 - 2020/JBM - Sammy Sadler feat Larry Stewart, Bluest Eyes in Texas - 1989 - 2021/BFD Part 4: - Clay Walker, Texas to Tennessee - You Look Good EP – 2021/Show Dog - Max Flinn, If I Didn't Love You - Meant to Be – 2021/MFM - Drew Baldridge, Stay At Home Dad - S - 2021/Pakota - Johnny Cash w Waylon Jennings, The Night Hank Williams Came to Town - Johnny Cash Is Coming To Town – 1987/Mercury

program Fred's Country 2021 w # 15 : since october 1983 Part 1: - The Grascals, feat Darryl Worley White Lightning - Country Calllic with a Bluegrass Spin - 211/Cracel Barrrel - Wynn Williams, F.M. 1885- Wynn Williams – 2020/WWM - Terry McBride, Callin' All Hearts- Rebels and Angels – 2020/MM - Brandi Behlen, Rodeo Man - Brandi Behlen – 2020/BBM - Cody Johnson feat Reba Mc Entire, Dear Rodeo - Ain' Nothin to it – 2019/CoJo-Warner Part 2: - Matt Mercado, Leaving Brownsville Tonight - S – 2020/MMM - Brian Callihan, Broke It Down - Brian Callihan – 2020/BCM - David Adam Byrnes, I Can Give You One - Neon Town – 2020/DABM - Max Flinn, If I Didn't Love You - S – 2020/MFM - Tyler Booth, Palomino Princess - S – 2020/TBM Part 3: - Jaden Hamilton, Bad Spot - S – 2021/JHM - Hayden Haddock, Honky Tonk On - Red Dirt Texas – 2020/Hayden Haddock Music,LLC - David Adam Byrnes, Old School - Neon Town – 2020/DABM - James Dupré, City Of Single Girls - Home and Away – 2020/Fleur de Magnolia Music Part 4: - Darin Morris Band, Wrap You Up In Love - S – 2021/MCA - Mich Rossel feat Thrisa Yearwood, - Ran into to You - S - 2021/ - Casey Chesnutt, Even Texas Couldn't Hold Her - S – 2021/ - Casey Baker, When The Party's All Over - S – 2020/CSBM

From the US, Texas & Canada 1st for Weekly neo-traditonal & classic Country program Fred's Country 2021 w # 11 : since october 1983 Part 1: - Wynonna, Girls With Guitars - Tell Me Why - 1994/MCA-Curb - Jon Pardi, Shame - Numbers on the Jukebox – 2020/No Dinero - Kaleb McIntire, Plano Texas - In These Shadowns – 2012/KMM - JoshTurner, I'll Fly Away - Country State Of Mind – 2020/MCA Part 2: - Hayden Haddock, Honky Tonk On - Red Dirt Texas – 2020/Hayden Haddock Music,LLC - Dustin Sonnier Misssin' You, Mississippi - Between the Stones and Jones – 2020/DSM - Max Flinn, If I Didn't Love You - S – 2020/MFM - Tyler Booth, Palomino Princess - S – 2020/TBM Part 3: - Jon Pardi, Tequila Little Time - Heartache Medication (Deluxe Version) – 2021/Capitol - Mo Pitney, Boy Gets The Girl - Ain't Lookin' Back – 2020/ - Eddie Rabbitt, Two Dollars In The Jukebox - Mountain Music – 1976/Elektra - Max Flinn, If I Didn't Love You - S – 2021/MMM - Tyler Booth, Palomino Princess - S – 2020/JBM Part 4: - David Adam Byrnes, I Can Give You One - Neon Town – 2020/DABM - Jaden Hamilton, Bad Spot - S – 2021/JHM - Terry McBride, Callin' All Hearts - S – 2020/TMM - Brian Callihan, Broke It Down. - Brian Callihan – 2020/BCM

From the US, Texas & Canada 1st for Weekly neo-traditonal & classic Country program Fred's Country 2021 w # 10 : since october 1983 Part 1: - Brad Paisley, Sleepin' On The Foldout - Who Needs Pictures - 1999/Arista - Jon Pardi, Tequila Little Time - Heartache Medication (Deluxe Version) – 2021/Capitol - Triston Marez, One Day - S – 2020/TMM - Jaden Hamilton, Bad Spot - S – 2021/JHM - Matt Mercado, A Cowboy's Life - S – 2020/MMM Part 2: - Matt Castillo, Leaving Brownsville Tonight - S – 2021/MCM - Hayden Haddock, Honky Tonk On - Red Dirt Texas – 2020/Hayden Haddock Music,LLC - David Adam Byrnes, Old School - Neon Town – 2020/DABM - Clayton Shay, Signed, Another Man - S – 2021/CSM - James Dupré, City Of Single Girls - Home and Away – 2020/Fleur de Magnolia Music - Max Flinn, If I Didn't Love You - S – 2021/MMM Part 3: - JoshTurner, Forever And Ever, Amen - Country State Of Mind – 2020/MCA - Mo Pitney, Boy Gets The Girl - Ain't Lookin' Back – 2020/ - Brooks & Dunn feat Tyler Booth, Lost and Found - Reboot – 2020/ - Wynn Williams, F.M. 1885 - Wynn Williams – 2020/WWM Part 4: - Cooper Wade, In The Middle of the Second Verse - I Ain't Playin' Around – 2018/CWM - Brandi Behlen, Gypsy - S – 2020/BBM - James Dupré, City Of Single Girls - Home and Away – 2020/Fleur de Magnolia Music - Curtis Grimes, Friends - S – 2021/CSM

From the US, Texas & Canada 1st for Weekly neo-traditonal & classic Country program Fred's Country 2021 w # 09 : since october 1983 Part 1: - Desert Rose Band feat Emmylou Harris, Price I Pay - A Dozen Roses - 1991/MCA-Curb - Matt Castillo, Leaving Brownsville Tonight - S – 2021/MCM - Terry McBride, Callin' All Hearts - S – 2020/TMM - Brian Callihan, Same Thing She Told Me - Brian Callihan – 2020/BCM - Dustin Sonnier, Missin' you, Mississippi - Between the Stones & Jones – 2019/DSE Part 2: - Hayden Haddock, Honky Tonk On - Red Dirt Texas – 2020/Hayden Haddock Music,LLC - David Adam Byrnes, Old School - Neon Town – 2020/DABM - James Dupré, City Of Single Girls - Home and Away – 2020/Fleur de Magnolia Music - Randall King, Hey Moon - Leana – 2020/WB - Gord Bamford, Postcards From Pasadena - Honkytonks And Heartaches – 2007/Royalty Part 3: - Josh Abbott Band, One More Two Step -The Highway Kind – 2020/Pretty Damn Tough - Tracy Millar, Loretta's Moonshine - I'm Not 29 No More – 2020 - Chad Cooke Band, Bringing Country Back - S – 2020/King Hall Music - Jaden Hamilton, Bad Spot - S – 2021/JHM Part 4: - Johnny Cash & Marty Stuart, I've Been Around - Forever Words – 2018/Legacy - Max Flinn, If I Didn't Love You - S – 2021/MMM - Tyler Booth, Palomino Princess - S – 2020/JBM - Darrin Morris Band, I Will - S – 2020/DMB

Today's Best & your All Time Favorites From the US, Texas & Canada 1st for Weekly neo-traditonal & classic Country program Fred's Country 2021 w # 08 : since october 1983 Part 1: - Alan Jackson,Thank God For The Radio - Who I Am - 1994/Arista - Clay Walker, Need a Bar Sometimes - S – 2020/Show Dog LLC - Josh Abbott Band, Settle Me Down - The Highway Kind – 2020/Pretty Damn Tough - Josh Abbott Band, One More Two Step -The Highway Kind – 2020/Pretty Damn Tough - Randall King, Hey Moon - Leana – 2020/WB Part 2: - Max Flinn, If I Didn't Love You - S – 2021/MMM - Kaitlyn Kohler, Too Many Love Songs - S – 2021/KMG - Brooks & Dunn feat Reba McEntire, Cowgirls Don't Cry - #1s ... and Then Some – 2009/Arista - Matt Mercado, A Cowboy's Life - S – 2021/MMM Part 3: - Drew Fish Band feat Pam Tillis, Every Damn Time - Every Damn Time – 2019/Reel - Triston Marez, One Day - S – 2021 - Granger Smith, Buy A Boy A Baseball - Country Things – 2020/Wheelhouse - Buck Owens vs Neal McCoy vs Charley Pride, Is Anybody Goin' to San Antone - Curtis Grimes, Friend - S – 2021/CGM Part 4: - James Dupré, City Of Single Girls - Home and Away – 2020/Fleur de Magnolia Music - Hayden Haddock, Honky Tonk On - Red Dirt Texas – 2020/Hayden Haddock Music,LLC - Jake Blocker, Blue Night - I Keep Forgetting – 2020/JBM - Clayton Shay, Signed, Another Man - S – 2021/CSM

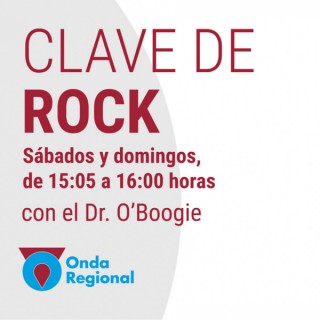

CLAVE DE ROCK T02C041 Sin saber por qué luchamos (07/02/2021)

...(con toques de soul) como los The Redhill Valleys, de Canada, también en el asunto de la roots music. Anda que la banda canadiense de once miembros de Toronto, Canadá, Samantha Martin & Delta Sugar, se las trae con su combinación de blues, soul, gospel y rock y voces excepcionales. Y qué decir del rockero aussie David Schaak o los Great Peacock, buen rock de ahora mismico. Pero no olvidamos a los Tennesee Champagne ni a la potente Jessie Wagner a la que se le caen los zapatos (y a nosotros la mandíbula escuchándola). Finalizamos con los estupendos Reckless Kelly, que los teníamos olvidados, hombre ya! Y de bonus, los 49 Winchester, ¡qué vergüenza!⦁ Whiskeyways, Juanita's⦁ The Whiskey Treaty Roadshow, Rose On the Vine ⦁ The Whiskey Treaty Roadshow, Rock & Roll Deja Vu⦁ The Redhill Valleys, If I Didn't Know You ⦁ Samantha Martin & Delta Sugar, I've Got A Feeling⦁ David Schaak, Honey Pot⦁ David Schaak, Lost, Alone and Lonesome ⦁ Great Peacock, Strange Position⦁ Great Peacock, High Wind⦁ Tennessee Champagne, Wicked⦁ Tennessee Champagne, Shake It⦁ Jessie Wagner, Shoes Droppin⦁ Keith Richards, I Wanna Be Your Man⦁ Reckless Kelly, Fightin' For⦁ 49 Winchester, It's A Shame

Chapter 236 - "If I Didn't Have Material Ready, I'd Be Way More Under Stress" ...as read by Julian Rosen of Common SageThis week we welcome Julian Rosen, frontman for the band Common Sage. Julian gives an overview of his musical influences and his band evolution, plus writing, recording, and not releasing music.Grab some Common Sage tunes - https://commonsage.bandcamp.com/You can also check out Julian's old band Davey Crockett - https://davey-crockett.bandcamp.com/----------Chapter 236 Music:Common Sage - "Wraparound Background"Common Sage - "Oh, December"Common Sage - "Saw Daddy"Common Sage - "Wet Grass"---As The Story Grows links:Help out at PatreonATSG WebsiteATSG Music and MerchJoin the Email ListATSG FacebookEmail: asthestorygrows@gmail.comYouTube - https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCNuP0_JUpT6DoIhhbGlwEYA?view_as=subscriber

Well, due to popular demand, the boys have compiled a long list of all the intro's from each episode from 2020."We hope you enjoy listening just as much as we enjoy playing them!" - Alex & CallumWant to contact the show? Email: motionspod@gmail.comFacebook: https://www.facebook.com/motionspod/Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/motions_pod/02:45 "Cantina Band" - Star Wars: A New Hope03:14 "The Riders of Rohan" - The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers03:49 "The Avengers" - Avengers Assemble 04:35 "Love Theme from the Godfather" - The Godfather05:10 "He's a Pirate" - Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl06:07 "I Wan'na Be Like You" - The Jungle Book06:54 "James Bond Theme" - James Bond08:17 "I Don't Want to Miss a Thing" - Armageddon09:23 "Stuck in the Middle With You" - Reservoir Dogs10:18 "Over the Rainbow" - The Wizard of Oz11:21 "Mrs Robinson" - The Graduate12:03 "Theme From Jurassic Park" - Jurassic Park13:17 "My Heart Will Go On (Love Theme from Titanic)" - Titanic14:34 "Forrest Gump Suite" - Forrest Gump15:34 "Remember Me" - Coco16:41 "When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs For Wings" - The Ballad of Buster Scruggs17:58 "The Rains of Castamere" - Game of Thrones19:36 "Kiss the Girl" - The Little Mermaid20:25 "The Avengers (slow)" - Avengers Infinity War/Endgame21:22 "Spiderman Theme" - Spiderman21:43 "If I Didn't Have You" - Monsters Inc.22:42 "Game of Thrones Theme" - Game of Thrones24:02 "Sherlock Theme" - Sherlock24:50 "Bang Bang" - Kill Bill Vol. 125:19 "Twisted Nerve" - Kill Bill Vol. 126:03 "The Lonely Shepherd" - Kill Bill Vol. 128:28 "Hallelujah" - Shrek29:45 "I Need a Hero" - Shrek 230:56 "Flight" - Man of Steel31:57 "The Blue Wrath" - Shaun of the Dead32:58 "This Is My World" - Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice34:01 "POSTERITY" Tenet34:47 "Romeo and Juliet" Hot Fuzz36:29 "Is She With You? (Wonder Woman Theme)" Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice37:14 "Happy Hour" - The Worlds End38:14 "Superman Theme" - Superman38:42 "Nemo Egg" - Finding Nemo39:57 "Africa" - Aquaman40:45 "My Shot" - Hamilton: An American Musical41:31 "Don't Stop Me Now" - Shazam!42:21 "Party in the U.S.A." - Pitch Perfect42:53 "Hit Me With Your Best Shot" - Birds of Prey43:40 "Journey to the Island" - Jurassic Park44:13 "Mess Around" - Planes, Trains & Automobiles45:04 "We Go Together" - Grease45:49 "White Christmas" - The Santa Clause47:14 "Somewhere in my Memory" - Home Alone47:57 "Auld Lang Syne" - Traditional See acast.com/privacy for privacy and opt-out information.

Taylor Swift Original Recordings Get Sold Again, New Jimi Hendrix Album Review and Who Are BTS Fans?

Poor Taylor Swift. Yet again, she gets screwed by Scooter Braun as he sells her original masters AGAIN for $300 million. We also try to figure out what type of people are actually listening to BTS making them the biggest band in the world, and how the NFL is also running into copyright music issues with the major record labels.MUSIC REVIEWS: "Who Am I" - Max Rogue "If I Didn't Love You" Frankie DaviesFRESH FINDS:ALBUMS:Live in Maui – Jimi HendrixGood News – Meagan Thee StallionFun – Garth Brooks My Brother's Keeper – Da Baby BE – BTS Copycat Killer' EP-Phoebe BridgersSINGLES:“Easy” - Mild Minds Remix, Tycho “You've Changed” – M Ward “Hurt” - Mumford & Sons Cover“Shark Tank” - Marty O'Reilly & The Old Soul Orchestra, Royal Jelly Jive“How Many Times?” – Joey Pecoraro.“Dreams” – Boyce Avenue Cover“Pain” – Ivy Club “Where I'm From” – Lukas Graham, feat Wiz Khalifa “chinatown”, “45”- Bleachers (Jack Antonoff) “Hey Boy” – Sia “A Dreamer's Holiday” - Julien BakerNOTABLY BAD:“Purple Blood” – Smashing Pumpkins “Somos Leoes” – Sublime UNCUT SUGGESTIONS:“Come Together” – Urbandawn, Tyson Kelly “Down for the Fifth Time” – Flamingosis “Oogum Boogum Song” – Brenton Wood “One More Day” – The Slingers “Country Road – Live at Santa Barbra, CA” – Jack Johnson, Paula Fuga“Layla” – Derek and the DominosBOURBON REVIEW: Stagg JR 3.2 out of 5 stars

"...if I haven't made you look like a superhero, I've failed..." In epi 14 of season 2, Kitty and Kevin chat with award-winning photographer, Dustin Jack. Dustin has been a pro photographer for over 30 years- shooting everything from rock stars to the Batmobile to Elvis's jumpsuits to landscapes and portraits. Dustin has shot over 200,000 images of guitars for Fretted Americana and designed all of their promo materials. He also directed and produced their YouTube channel's "The Phil X Show". Dustin was named "Photoshop Guru" in 2013 and 2019 and has won multiple awards for his concert photos. You can read more about Dustin on his website- dustinjackphotography.comWe talk with Dustin about designing/shooting the promo shots for the Mötley Crüe/Def Leppard Stadium Tour (rescheduled for 2021?????), reminisce about the 80s, and Kitty shares the story of how she found Dustin via Nikki Sixx's Instagram page and how Dustin blackmailed her to have him on the show. Additionally, Dustin shares what gear he uses to shoot live concerts and portraits. If you love Mötley Crüe and 80s metal bands, this show is for you! See the photos on our Instagram page.Please note- this show was recorded on October 31st, 2020. Also-this one is about sex, drugs, and rock and roll, so it may not be suitable for children. Bookmarks (ish):1:04 Greetings and Salutations2:22 Background7:40 Blackmail12:20 Kitty Meets Nikki Sixx14:50 Stadium Shoot16:55 Nikki's photography21:24 Shooting Backstage/Photo Pit 26:44 Starstruck30:15 Back to the Stadium Shoot35:20 If I Didn't Make You Look Like A Super Hero, I Failed43:40 Editing Process47:13 Set It & Forget It?49:47 Your Friend, Randy Johnson51:03 Darkroom to Digital53:41 Never Stop Learning54:10 How Big Is Your Rig?59:25 The Tree1:05:06 OutroSupport the show (https://urbanromantix.com/podcast)

In which I quickly get off the topic of birthday wishes to my favorite transdude YouTuber and ramble about my own transition, depilating, autism, motivations of abusers & bullies, feedback, and being bass-ackwards AF.Tim Minchin's full, uncut 'If I Didn't Have You': https://youtu.be/Zn6gV2sdl38

Gospel According to Pixar: If I Didn't Have You with Mark Burrows

Pixar Month plunges on, and this week we have a composer, musician, worship leader, educator, and all-around-great guy Mark Burrows. Joining us in the WHEEL Studios (Nichols Hills auxiliary) is my co-host Suzann Wade. Whilst Mark Suzann and I would normally catch up with some chips and salsa at Blue Mesa, these are unprecedented times, so we catch up on the zoom and let you nosey people listen in.Mark talks about the challenges of the sacred music biz during a pandemic, the horrors of poorly-written childrens religious curriculum, the power of puppetry, and how Pixar smashed the Disney Princess formula.Mark brings to the table "If I Didn't Have You" from Monster's Inc. Then the WHEEL chooses something so incongruous that Daniel forces a re-spin.You can join Mark every Sunday (virtually at least) at Fort Worth First United Methodist Church, and really there's no reason you shouldn't.

몬스터주식회사 OST / Monsters, inc. OST 1. If I Didn't Have You 2. Monsters, Inc. 3. The Scare Floor 4. Boo's Tired 5. Enter The Heroes 6. Walk To Work

This hour promises an abundance of top quality tracks you'll love. This train is barreling forward with signs of stopping. Get on board!!! FACEBOOK: facebook.com/ontargetpodcast INSTAGRAM: instagram.com/modmarty TWITTER: twitter.com/modmarty ----------------------------------------------- The Playlist Is: "Baby Don't Leave Me" Jimmy Ricks - Jubilee "Three Little Pigs" Lloyd Price - Spaton "Loop De Loop" Johnny Thunder - Diamond "Have Love Will Travel" The Off-Beats - Guyden "Copy Cat" The Cadillacs - Jubilee "The Sock" The Sharpees - One-Derful "Jump And Dance" The Carnaby - Piccadilly "Love Me Baby" Jon & Robin And The In Crowd - Abnak "Caio Baby" Lynne Randell - Columbia "(Come On And Be My) Sweet Darlin'" Jimmy 'Soul' Clark - Soulhawk "Chains Of Love" Candy & The Kisses - Decca "The Duck" Bobby Freeman - Autumn "Soul Party" Billy Clark & The Maskman - Disc'Az "Top Twenty" Bunny Shivel - Capitol "I Miss You Baby (How I Miss You)" Marv Johnson - Tamla-Motown "Hand Clappin' Time" Gino - Golden Crest "Ever Lasting Love" Robert Knight - Rising Sons "Hard Time For Young Lovers" Eddie Hodges - Aurora "Try Me And See" Ruth Brown - Skye "So Much Love" Faith Hope & Charity - Crewe "If I Didn't Love You" The Profiles - Duo "Doodlum" The Off-Beats - Guyden

HARLEM. IF I DIDN’T MEAN YOU WELL. DON’T IT MAKE IT BETTER. DELLA REESE WHO IS SHE AND WHAT IS SHE TO YOU. I WANT TO SPEND THE NIGHT. USE ME. LONELY TOWN, LONELY STREET. GIL SCOTT-HERON GRANDMA’S HANDS. MAKE A SMILE FOR ME. MAKE LOVE TO YOUR MIND. OH YEAH! SPANKY WILSON KISSING MY LOVE. HOPE SHE’LL BE HAPPIER (LIVE) ARETHA FRANKLIN LET ME IN YOUR LIFE. I WISH YOU WELL. THEN YOU SMILE AT ME. SYREETA LET ME BE THE ONE YOU NEED. FAMILY TABLE. SHE’S LONELY. LYN COLLINS AIN’T NO SUNSHINE. CAN WE PRETEND? LOVE IS. GLADYS KNIGHT & THE PIPS WHO IS SHE (AND WHAT IS SHE TO YOU)? I WANT TO SPEND THE NIGHT. LEAN ON ME (LIVE). RAILROAD MAN. I’LL BE WITH YOU. ESTHER PHILLIPS LET ME IN YOUR LIFE. BETTER DAYS (THEME FROM “MAN AND BOY”). LOVELY NIGHT FOR DANCING (7” VERSION). CAROLYN FRANKLIN SWEET NAOMI. WORLD KEEPS TURNING (LIVE). YOU JUST CAN’T SMILE IT AWAY. THE BEST YOU CAN. GLADYS KNIGHT & THE PIPS BETTER YOU GO YOUR WAY. RALPH MACDONALD IN THE NAME OF LOVE (7” VERSION) THE CRUSADERS SOUL SHADOWS (7” VERSION) HELLO LIKE BEFORE. DIANA ROSS THE SAME LOVE THAT MADE ME LAUGH. TENDER THINGS. GROVER WASHINGTON, JR. JUST THE TWO OF US (7” VERSION). MEMORIES ARE THAT WAY. I CAN’T WRITE LEFT-HANDED (LIVE).

This week we shine a spotlight on some of our favourites and often played gems. We revisit some big hits and discover some new-to-us awesomeness. Mod Marty is in BC this week which means look out for more great tunes dropping in the next show when he gets back. FACEBOOK: facebook.com/ontargetpodcast INSTAGRAM: instagram.com/modmarty TWITTER: twitter.com/modmarty ----------------------------------------------- The Playlist Is: "Eleanore Rigby" Aretha Franklin - Atlantic "Thanks A Lot" Brenda Lee - Decca "I Know That He Loves Me" Theola Kilgore - Reo "Going To A Happening" Tommy Neal - PaMeLiNe "Cool Pearl" The Capitols - Karen "Just One Look" The Soul Twins - Karen "We'll Be Dancing On The Moon" Trade Martin - Coed "If I Didn't Love You Girl" Travis Pike's Tea Party - RnB "Everybody Needs A Little Love" Bern Elliot & The Fenmen - London "What A Man" Linda Lyndell - Volt "A Woman Was Made For A Man" Barbara Trent ft. Richi Corbin Trio - Red "90 day freeze (On Her Love)" 100 Proof (Aged In Soul) - Buddah "You're Just A Fool In Love" Dee Dee Sharpe - Atco "Shake A Tail Feather" Ray Charles - Atlantic "I Don't Know" Linda Lyndell - Volt "Hey Sister" Monguito Santamaria - Discjockey "Skinny Minnie" Gerry & The Pacemakers - Capitol "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" The Righteous Brothers - Philles "Don't Wait Too Long" Bettye Swann - Money "Since I Lost The One I Love" The Impressions - ABC-Paramount "The Slush" Bill doggett - King

We McDonald’s star-making turn on her show-stopping blind audition on the hit NBC TV show The Voice drew national attention in 2016. It was the kind of momentous debut she had been preparing for her entire life. Singing since the age of 12, We attended the Harlem School for the Arts after school and on weekends, where she studied theater, piano and further cultivated her unique and righteously robust voice. We McDonald is a singer, and songwriter and that has been touring internationally and sharing her sultry vocal gift with the world. In 2017, We had the opportunity of appearing on the Emmy Award winning PBS Gershwin Awards honoring Legend Tony Bennett. And, in 2018 she belted the National Anthem at Yankee Stadium. Available now is her latest single “If I Didn’t Love You”, released early 2019. Late 2019 her self-titled EP is scheduled to be released featuring a diverse slate of songs written by We that showcase her soaring vocal presence. A newly published children’s and young adult book author, We released: Make It Happen! We McDonald: Singer, part of the Make It Happen! series of books that help middle school students build skills to reach their own goals; and a picture book, The Little Girl with The Big Voice, written by We for younger children. We’s captivating story as a singer, songwriter and as a teenager courageously embracing her uniqueness resonates with kids as well as adults looking to expand their own understanding of themselves and the world around them.

We McDonald’s star-making turn on her show-stopping blind audition on the hit NBC TV show, The Voice, drew national attention in 2016. It was the kind of momentous debut she had been preparing for her entire life. Singing since the age of 12, We attended the Harlem School for the Arts after school and on weekends, where she studied theater, piano and further cultivated her unique and righteously robust voice. We McDonald is a singer, and songwriter and that has been touring internationally and sharing her sultry vocal gift with the world. In 2017, We had the opportunity of appearing on the Emmy Award winning PBS Gershwin Awards honoring Legend Tony Bennett. And, in 2018 she belted the National Anthem at Yankee Stadium. Available now is her latest single “If I Didn’t Love You”, released early 2019. Late 2019 her self-titled EP is scheduled to be released featuring a diverse slate of songs written by We that showcase her soaring vocal presence. A newly published children’s and young adult book author, We released: Make It Happen! We McDonald: Singer, part of the Make It Happen! series of books that help middle school students build skills to reach their own goals; and a picture book, The Little Girl with The Big Voice, written by We for younger children. We’s captivating story as a singer, songwriter and as a teenager courageously embracing her uniqueness resonates with kids as well as adults looking to expand their own understanding of themselves and the world around them.

Suggestible things to watch, read and listen to. Hosted by James Clement @mrsundaymovies and Claire Tonti @clairetonti.Visit https://bigsandwich.co/ for a bonus weekly show, a monthly commentary, early stuff and an ad free podcast feed for $9 per month.Plus OneTim Minchin’s If I Didn’t Have YouDefending JacobUnlocking UsI’m Still Here by Austin Channing BrownRandy Writes A NovelSend your recommendations to suggestiblepod@gmail.com, we’d love to hear them.You can also follow the show on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook @suggestiblepod and join our ‘Planet Broadcasting Great Mates OFFICIAL’ Facebook Group. So many things. See acast.com/privacy for privacy and opt-out information.

Episode Sixty: "You Send Me" by Sam Cooke

Episode sixty of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs looks at "You Send Me" by Sam Cooke Click the full post to read liner notes, links to more information, and a transcript of the episode. Patreon backers also have a ten-minute bonus episode available, on "Little Darlin'" by The Gladiolas. Also, an announcement -- the book version of the first fifty episodes is now available for purchase. See the show notes, or the previous mini-episode announcing this, for details. ----more---- Resources The Mixcloud is slightly delayed this week. I'll update the post tonight with the link. My main source for this episode is Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke by Peter Guralnick. Like all Guralnick's work, it's an essential book if you're even slightly interested in the subject. This is the best compilation of Sam Cooke's music for the beginner. A note on spelling: Sam Cooke was born Sam Cook, the rest of his family all kept the surname Cook, and he only added the "e" from the release of "You Send Me", so for almost all the time covered in this episode he was Cook. I didn't feel the need to mention this in the podcast, as the two names are pronounced identically. I've spelled him as Cooke and everyone else as Cook throughout. Book of the Podcast Remember that there's a book available based on the first fifty episodes of the podcast. You can buy it at this link, which will take you to your preferred online bookstore. Patreon This podcast is brought to you by the generosity of my backers on Patreon. Why not join them? Transcript We've talked before about how the music that became known as soul had its roots in gospel music, but today we're going to have a look at the first big star of that music to get his start as a professional gospel singer, rather than as a rhythm and blues singer who included a little bit of gospel feeling. Sam Cooke was, in many ways, the most important black musician of the late fifties and early sixties, and without him it's doubtful whether we would have the genre of soul as we know it today. But when he started out, he was someone who worked exclusively in the gospel field, and within that field he was something of a superstar. He was also someone who, as admirable as he was as a singer, was far less admirable in his behaviour towards other people, especially the women in his life, and while that's something that will come up more in future episodes, it's worth noting here. Cooke started out as a teenager in the 1940s, performing in gospel groups around Chicago, which as we've talked about before was the city where a whole new form of gospel music was being created at that point, spearheaded by Thomas Dorsey. Dorsey, Mahalia Jackson, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe were all living and performing in the city during young Sam's formative years, but the biggest influence on him was a group called the Soul Stirrers. The Soul Stirrers had started out in 1926 as a group in what was called the "jubilee" style -- the style that black singers of spiritual music sang in the period before Thomas Dorsey revolutionised gospel music. There are no recordings of the Soul Stirrers in that style, but this is probably the most famous jubilee recording: [Excerpt: The Fisk Jubilee Singers, "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot"] But as Thomas Dorsey and the musicians around him started to create the music we now think of as gospel, the Soul Stirrers switched styles, and became one of the first -- and best -- gospel quartets in the new style. In the late forties, the Soul Stirrers signed to Specialty Records, one of the first acts to sign to the label, and recorded a series of classic singles led by R.H. Harris, who was regarded by many as the greatest gospel singer of the age: [Excerpt: The Soul Stirrers feat. R.H. Harris, "In That Awful Hour"] Sam Cooke was one of seven children, the son of Reverend Charles Cook and his wife Annie Mae, and from a very early age the Reverend Cook had been training them as singers -- five of them would perform regularly around churches in the area, under the name The Singing Children. Young Sam was taught religion by his father, but he was also taught that there was no prohibition in the Bible against worldly success. Indeed the Reverend Cook taught him two things that would matter in his life even more than his religion would. The first was that whatever it is you do in life, you try to do it the best you can -- you never do anything by halves, and if a thing's worth doing it's worth doing properly. And the second was that you do whatever is necessary to give yourself the best possible life, and don't worry about who you step on to do it. After spending some time with his family group, Cooke joined a newly-formed gospel group, who had heard him singing the Ink Spots song "If I Didn't Care" to a girl. That group was called the Highway QCs, and a version of the group still exists to this day. Sam Cooke only stayed with them a couple of years, and never recorded with them, but they replaced him with a soundalike singer, Johnnie Taylor, and listening to Taylor's recordings with the group you can get some idea of what they sounded like when Sam was a member: [Excerpt: Johnnie Taylor and the Highway QCs, "I Dreamed That Heaven Was Like This"] The rest of the group were decent singers, but Sam Cooke was absolutely unquestionably the star of the Highway QCs. Creadell Copeland, one of the group's members, later said “All we had to do was stand behind Sam. Our claim to fame was that Sam’s voice was so captivating we didn’t have to do anything else.” The group didn't make a huge amount of money, and they kept talking about going in a pop direction, rather than just singing gospel songs, and Sam was certainly singing a lot of secular music in his own time -- he loved gospel music as much as anyone, but he was also learning from people like Gene Autry or Bill Kenny of the Ink Spots, and he was slowly developing into a singer who could do absolutely anything with his voice. But his biggest influence was still R.H. Harris of the Soul Stirrers, who was the most important person in the gospel quartet field. This wasn't just because he was the most talented of all the quartet singers -- though he was, and that was certainly part of it -- but because he was the joint leader of a movement to professionalise the gospel quartet movement. (Just as a quick explanation -- in both black gospel, and in the white gospel music euphemistically called "Southern Gospel", the term "quartet" is used for groups which might have five, six, or even more people in them. I'll generally refer to all of these as "groups", because I'm not from the gospel world, but I'll use the term "quartet" when talking about things like the National Quartet Convention, and I may slip between the two interchangeably at times. Just know that if I mention quartets, I'm not just talking about groups with exactly four people in them). Harris worked with a less well known singer called Abraham Battle, and with Charlie Bridges, of another popular group, the Famous Blue Jays: [Excerpt: The Famous Blue Jay Singers, “Praising Jesus Evermore”] Together they founded the National Quartet Convention, which existed to try to take all the young gospel quartets who were springing up all over the place, and most of whom had casual attitudes to their music and their onstage appearance, and teach them how to comport themselves in a manner that the organisation's leaders considered appropriate for a gospel singer. The Highway QCs joined the Convention, of course, and they considered themselves to be disciples, in a sense, of the Soul Stirrers, who they simultaneously considered to be their mentors and thought were jealous of the QCs. It was normal at the time for gospel groups to turn up at each other's shows, and if they were popular enough they would be invited up to sing, and sometimes even take over the show. When the Highway QCs turned up at Soul Stirrers shows, though, the Soul Stirrers would act as if they didn't know them, and would only invite them on to the stage if the audience absolutely insisted, and would then limit their performance to a single song. From the Highway QCs' point of view, the only possible explanation was that the Soul Stirrers were terrified of the competition. A more likely explanation is probably that they were just more interested in putting on their own show than in giving space to some young kids who thought they were the next big thing. On the other hand, to all the younger kids around Chicago, the Highway QCs were clearly the group to beat -- and people like a young singer named Lou Rawls looked up to them as something to aspire to. And soon the QCs found themselves being mentored by R.B. Robinson, one of the Soul Stirrers. Robinson would train them, and help them get better gigs, and the QCs became convinced that they were headed for the big time. But it turned out that behind the scenes, there had been trouble in the Soul Stirrers. Harris had, more and more, come to think of himself as the real star of the group, and quit to go solo. It had looked likely for a while that he would do so, and when Robinson had appeared to be mentoring the QCs, what he was actually doing was training their lead singer, so that when R.H. Harris eventually quit, they would have someone to take his place. The other Highway QCs were heartbroken, but Sam took the advice of his father, the Reverend Cook, who told him "Anytime you can make a step higher, you go higher. Don’t worry about the other fellow. You hold up for other folks, and they’ll take advantage of you." And so, in March 1951, Sam Cooke went into the studio with the Soul Stirrers for his first ever recording session, three months after joining the group. Art Rupe, the head of Specialty Records, was not at all impressed that the group had got a new singer without telling him. Rupe had to admit that Cooke could sing, but his performance on the first few songs, while impressive, was no R.H. Harris: [Excerpt: the Soul Stirrers, "Come, Let Us Go Back to God"] But towards the end of the session, the Soul Stirrers insisted that they should record "Jesus Gave Me Water", a song that had always been a highlight of the Highway QCs' set. Rupe thought that this was ridiculous -- the Pilgrim Travellers had just had a hit with the song, on Specialty, not six months earlier. What could Specialty possibly do with another version of the song so soon afterwards? But the group insisted, and the result was absolutely majestic: [Excerpt: The Soul Stirrers, "Jesus Gave Me Water"] Rupe lost his misgivings, both about the song and about the singer -- that was clearly going to be the group's next single. The group themselves were still not completely sure about Cooke as their singer -- he was younger than the rest of them, and he didn't have Harris' assurance and professionalism, yet. But they knew they had something with that song, which was released with "Peace in the Valley" on the B-side. That song had been written by Thomas Dorsey fourteen years earlier, but this was the first time it had been released on a record, at least by anyone of any prominence. "Jesus Gave Me Water" was a hit, but the follow-ups were less successful, and meanwhile Art Rupe was starting to see the commercial potential in black styles of music other than gospel. Even though Rupe loved gospel music, he realised when "Lawdy Miss Clawdy" became the biggest hit Specialty had ever had to that point that maybe he should refocus the label away from gospel and towards more secular styles of music. “Jesus Gave Me Water” had consolidated Sam as the lead singer of the Soul Stirrers, but while he was singing gospel, he wasn't living a very godly life. He got married in 1953, but he'd already had at least one child with another woman, who he left with the baby, and he was sleeping around constantly while on the road, and more than once the women involved became pregnant. But Cooke treated women the same way he treated the groups he was in – use them for as long as they've got something you want, and then immediately cast them aside once it became inconvenient. For the next few years, the Soul Stirrers would have one recording session every year, and the group continued touring, but they didn't have any breakout success, even as other Specialty acts like Lloyd Price, Jesse Belvin, and Guitar Slim were all selling hand over fist. The Soul Stirrers were more popular as a live act than as a recording act, and hearing the live recording of them that Bumps Blackwell produced in 1955, it's easy to see why: [Excerpt: Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, "Nearer to Thee"] Bumps Blackwell was convinced that Cooke needed to go solo and become a pop singer, and he was more convinced than ever when he produced the Soul Stirrers in the studio for the first time. The reason, actually, was to do with Cooke's laziness. They'd gone into the studio, and it turned out that Cooke hadn't written a song, and they needed one. The rest of the group were upset with him, and he just told them to hand him a Bible. He started flipping through, skimming to find something, and then he said "I got one". He told the guitarist to play a couple of chords, and he started singing -- and the song that came out, improvised off the top of his head, "Touch the Hem of His Garment", was perfect just as it was, and the group quickly cut it: [Excerpt: Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, "Touch the Hem of His Garment"] Blackwell knew then that Cooke was a very, very special talent, and he and the rest of the people at Specialty became more and more insistent as 1956 went on that Sam Cooke should become a secular solo performer, rather than performing in a gospel group. The Soul Stirrers were only selling in the low tens of thousands -- a reasonable amount for a gospel group, but hardly the kind of numbers that would make anyone rich. Meanwhile, gospel-inspired performers were having massive hits with gospel songs with a couple of words changed. There's an episode of South Park where they make fun of contemporary Christian music, saying you just have to take a normal song and change the word "Baby" to "Jesus". In the mid-fifties things seemed to be the other way -- people were having hits by taking Gospel songs and changing the word "Jesus" to "baby", or near as damnit. Most famously and blatantly, there was Ray Charles, who did things like take "This Little Light of Mine": [Excerpt: The Louvin Brothers, "This Little Light of Mine"] and turn it into "This Little Girl of Mine: [Excerpt: Ray Charles, "This Little Girl of Mine"] But there were a number of other acts doing things that weren't that much less blatant. And so Sam Cooke travelled to New Orleans, to record in Cosimo Matassa's studio with the same musicians who had been responsible for so many rock and roll hits. Or, rather, Dale Cook did. Sam was still a member of the Soul Stirrers at the time, and while he wanted to make himself into a star, he was also concerned that if he recorded secular music under his own name, he would damage his career as a gospel singer, without necessarily getting a better career to replace it. So the decision was made to put the single out under the name "Dale Cook", and maintain a small amount of plausible deniability. If necessary, they could say that Dale was Sam's brother, because it was fairly well known that Sam came from a singing family, and indeed Sam's brother L.C. (whose name was just the initials L.C.) later went on to have some minor success as a singer himself, in a style very like Sam's. As his first secular recording, they decided to record a new version of a gospel song that Cooke had recorded with the Soul Stirrers, "Wonderful": [Excerpt: Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, "Wonderful"] One quick rewrite later, and that song became, instead, "Lovable": [Excerpt: Dale Cook, "Lovable"] Around the time of the Dale Cook recording session, Sam's brother L.C. went to Memphis, with his own group, where they appeared at the bottom of the bill for a charity Christmas show in aid of impoverished black youth. The lineup of the show was almost entirely black – people like Ray Charles, B.B. King, Rufus Thomas, and so on – but Elvis Presley turned up briefly to come out on stage and wave to the crowd and say a few words – the Colonel wouldn't allow him to perform without getting paid, but did allow him to make an appearance, and he wanted to support the black community in Memphis. Backstage, Elvis was happy to meet all the acts, but when he found out that L.C. was Sam's brother, he spent a full twenty minutes talking to L.C. about how great Sam was, and how much he admired his singing with the Soul Stirrers. Sam was such a distinctive voice that while the single came out as by "Dale Cook", the DJs playing it would often introduce it as being by "Dale Sam Cook", and the Soul Stirrers started to be asked if they were going to sing "Lovable" in their shows. Sam started to have doubts as to whether this move towards a pop style was really a good idea, and remained with the Soul Stirrers for the moment, though it's noticeable that songs like "Mean Old World" could easily be refigured into being secular songs, and have only a minimal amount of religious content: [Excerpt: Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, "Mean Old World"] But barely a week after the session that produced “Mean Old World”, Sam was sending Bumps Blackwell demos of new pop songs he'd written, which he thought Blackwell would be interested in producing. Sam Cooke was going to treat the Soul Stirrers the same way he'd treated the Highway QCs. Cooke flew to LA, to meet with Blackwell and with Clifton White, a musician who had been for a long time the guitarist for the Mills Brothers, but who had recently left the band and started working with Blackwell as a session player. White was very unimpressed with Cooke – he thought that the new song Cooke sang to them, "You Send Me", was just him repeating the same thing over and over again. Art Rupe helped them whittle the song choices down to four. Rupe had very particular ideas about what made for a commercial record – for example, that a record had to be exactly two minutes and twenty seconds long – and the final choices for the session were made with Rupe's criteria in mind. The songs chosen were "Summertime", "You Send Me", another song Sam had written called "You Were Made For Me", and "Things You Do to Me", which was written by a young man Bumps Blackwell had just taken on as his assistant, named Sonny Bono. The recording session should have been completely straightforward. Blackwell supervised it, and while the session was in LA, almost everyone there was a veteran New Orleans player – along with Clif White on guitar there was René Hall, a guitarist from New Orleans who had recently quit Billy Ward and the Dominoes, and acted as instrumental arranger; Harold Battiste, a New Orleans saxophone player who Bumps had taken under his wing, and who wasn't playing on the session but ended up writing the vocal arrangements for the backing singers; Earl Palmer, who had just moved to LA from New Orleans and was starting to make a name for himself as a session player there after his years of playing with Little Richard, Lloyd Price, and Fats Domino in Cosimo Matassa's studio, and Ted Brinson, the only LA native, on bass -- Brinson was a regular player on Specialty sessions, and also had connections with almost every LA R&B act, to the extent that it was his garage that "Earth Angel" by the Penguins had been recorded in. And on backing vocals were the Lee Gotch singers, a white vocal group who were among the most in-demand vocalists in LA. So this should have been a straightforward session, and it was, until Art Rupe turned up just after they'd recorded "You Send Me": [Excerpt: Sam Cooke, "You Send Me"] Rupe was horrified that Bumps and Battiste had put white backing vocalists behind Cooke's vocals. They were, in Rupe's view, trying to make Sam Cooke sound like Billy Ward and his Dominoes at best, and like a symphony orchestra at worst. The Billy Ward reference was because René Hall had recently arranged a version of "Stardust" for the Dominoes: [Excerpt: Billy Ward and the Dominoes, "Stardust"] And the new version of "Summertime" had some of the same feel: [Excerpt: Sam Cooke, "Summertime"] If Sam Cooke was going to record for Specialty, he wasn't going to have *white* vocalists backing him. Rupe wanted black music, not something trying to be white -- and the fact that he, a white man, was telling a room full of black musicians what counted as black music, was not lost on Bumps Blackwell. Even worse than the whiteness of the singers, though, was that some of them were women. Rupe and Blackwell had already had one massive falling-out, over "Rip it Up" by Little Richard. When they'd agreed to record that, Blackwell had worked out an arrangement beforehand that Rupe was happy with -- one that was based around piano triplets. But then, when he'd been on the plane to the session, Blackwell had hit upon another idea -- to base the song around a particular drum pattern: [Excerpt: Little Richard, "Rip it Up"] Rupe had nearly fired Blackwell over that, and only relented when the record became a massive hit. Now that instead of putting a male black gospel group behind Cooke, as agreed, Blackwell had disobeyed him a second time and put white vocalists, including women, behind him, Rupe decided it was the last straw. Blackwell had to go. He was also convinced that Sam Cooke was only after money, because once Cooke discovered that his solo contract only paid him a third of the royalties that the Soul Stirrers had been getting as a group, he started pushing for a greater share of the money. Rupe didn't like that kind of greed from his artists -- why *should* he pay the artist more than one cent per record sold? But he still owed Blackwell a great deal of money. They eventually came to an agreement -- Blackwell would leave Specialty, and take Sam Cooke, and Cooke's existing recordings with him, since he was so convinced that they were going to be a hit. Rupe would keep the publishing rights to any songs Sam wrote, and would have an option on eight further Sam Cooke recordings in the future, but Cooke and Blackwell were free to take "You Send Me", "Summertime", and the rest to a new label that wanted them for its first release, Keen. While they waited around for Keen to get itself set up, Sam made himself firmly a part of the Central Avenue music scene, hanging around with Gaynel Hodge, Jesse Belvin, Dootsie Williams, Googie Rene, John Dolphin, and everyone else who was part of the LA R&B community. Meanwhile, the Soul Stirrers got Johnnie Taylor, the man who had replaced Sam in the Highway QCs, to replace him in the Stirrers. While Sam was out of the group, for the next few years he would be regularly involved with them, helping them out in recording sessions, producing them, and more. When the single came out, everyone thought that "Summertime" would be the hit, but "You Send Me" quickly found itself all over the airwaves and became massive: [Excerpt: Sam Cooke, "You Send Me"] Several cover versions came out almost immediately. Sam and Bumps didn't mind the versions by Jesse Belvin: [Excerpt: Jesse Belvin, "You Send Me"] Or Cornell Gunter: [Excerpt: Cornell Gunter, "You Send Me"] They were friends and colleagues, and good luck to them if they had a hit with the song -- and anyway, they knew that Sam's version was better. What they did object to was the white cover version by Teresa Brewer: [Excerpt: Teresa Brewer, "You Send Me"] Even though her version was less of a soundalike than the other LA R&B versions, it was more offensive to them -- she was even copying Sam's "whoa-oh"s. She was nothing more than a thief, Blackwell argued -- and her version was charting, and made the top ten. Fortunately for them, Sam's version went to number one, on both the R&B and pop charts, despite a catastrophic appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, which accidentally cut him off half way through a song. But there was still trouble with Art Rupe. Sam was still signed to Rupe's company as a songwriter, and so he'd put "You Send Me" in the name of his brother L.C., so Rupe wouldn't get any royalties. Rupe started legal action against him, and meanwhile, he took a demo Sam had recorded, "I'll Come Running Back To You", and got René Hall and the Lee Gotch singers, the very people whose work on "You Send Me" and "Summertime" he'd despised so much, to record overdubs to make it sound as much like "You Send Me" as possible: [Excerpt: Sam Cooke, "I'll Come Running Back To You"] And in retaliation for *that* being released, Bumps Blackwell took a song that he'd recorded months earlier with Little Richard, but which still hadn't been released, and got the Specialty duo Don and Dewey to provide instrumental backing for a vocal group called the Valiants, and put it out on Keen: [Excerpt: The Valiants, "Good Golly Miss Molly"] Specialty had to rush-release Little Richard's version to make sure it became the hit -- a blow for them, given that they were trying to dripfeed the public what few Little Richard recordings they had left. As 1957 drew to a close, Sam Cooke was on top of the world. But the seeds of his downfall were already in place. He was upsetting all the right people with his desire to have control of his own career, but he was also hurting a lot of other people along the way -- people who had helped him, like the Highway QCs and the Soul Stirrers, and especially women. He was about to divorce his first wife, and he had fathered a string of children with different women, all of whom he refused to acknowledge or support. He was taking his father's maxims about only looking after yourself, and applying them to every aspect of life, with no regard to who it hurt. But such was his talent and charm, that even the people he hurt ended up defending him. Over the next couple of times we see Sam Cooke, we'll see him rising to ever greater artistic heights, but we'll also see the damage he caused to himself and to others. Because the story of Sam Cooke gets very, very unpleasant.

Episode Sixty: “You Send Me” by Sam Cooke