Podcasts about luigi galvani

- 30PODCASTS

- 32EPISODES

- 37mAVG DURATION

- ?INFREQUENT EPISODES

- Oct 24, 2025LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about luigi galvani

Latest news about luigi galvani

- From brain Bluetooth to ‘full RoboCop’: where chip implants will be heading soon English – The Conversation - Apr 11, 2025

- 'Foul and loathsome’ or jewels of the natural world? The complicated history of human-frog relations Environment + Energy – The Conversation - Dec 27, 2023

- Daily Quiz | On Italian physicist and philosopher Luigi Galvani The Hindu - Science - Dec 4, 2023

- Interview: C. E. McGill, author of Our Hideous Progeny Fantasy Book Critic - Jun 12, 2023

- The Electrome: The Next Great Frontier For Biomedical Technology IEEE Spectrum - May 23, 2023

Latest podcast episodes about luigi galvani

Ep 267 is loose! And it being spooky season, we thought we should explore another 'Universal Monster' and dive into the history of Frankenstein!Who or what was the inspiration for Mary Shelley's great gothic novel? What crazy experiments were carried out in the pursuit of beating death? And how do you like your frogs' legs?The secret ingredient is...electricity!Here is the link to the Castle Frankenstein hoax broadcast: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yYGRx1gDKgoGet cocktails, poisoning stories and historical true crime tales every week by following and subscribing to The Poisoners' Cabinet wherever you get your podcasts. Find us and our cocktails at www.thepoisonerscabinet.com Join us Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thepoisonerscabinet Find us on TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@thepoisonerscabinet Follow us on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/thepoisonerscabinet/ Find us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ThePoisonersCabinet Listen on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@ThePoisonersCabinet Sources this week include biographies of Mary Shelley, Johann Dippel, Alessandro Volta, and Luigi Galvani, as well as Kathryn Harkup's Making the Monster, and the novel Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Plus:https://www.exclassics.com/newgate/ng464.htmhttps://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tcr.202500043https://publishing.rcseng.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1308/147363513X13500508916973https://europe.stripes.com/your-community/frankenstein's-castle-and-a-halloween-prank-that-went-viral.htmlhttps://allthatsinteresting.com/real-frankenstein-experiments/6https://theconversation.com/frankenstein-the-real-experiments-that-inspired-the-fictional-science-105076 Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

#1 - Elektriciteit in het lichaam - Elektriciteit in het brein (S13)

Elektriciteit stroomt door ons lichaam. Elke beweging, emotie en beslissing wordt aangestuurd door elektrische impulsen in de hersenen. Luigi Galvani en zijn vrouw Lucia Galeazzi ontdekten samen voor het eerst elektriciteit vanuit het lichaam. We maken een sprong naar 250 jaar later. "Veel mensen realiseren zich niet dat het lichaam alleen maar kan werken dankzij elektriciteit,” zegt Damiaan Denys, filosoof en hoogleraar psychiatrie aan het Amsterdam UMC. Maar wat doet die stroom eigenlijk met ons? En kunnen we die inzetten in ons voordeel? In deze Focus aflevering duiken we diep in het brein: ⚡Damiaan Denys (https://www.damiaandenys.com/) onderzoekt Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) en laat zien hoe gecontroleerde elektrische stroompjes gedrag kunnen beïnvloeden en zelfs depressie kunnen verlichten. “In tegenstelling tot andere therapieën, zag je mensen eigenlijk in een milliseconde verbeteren.”

Vinti 2 mln Lotteria Italia in pasticceria di Palermo "Siamo felici"

PALERMO (ITALPRESS) - "Speravo che il biglietto fosse rimasto a me, ma non è stato così. Comunque, sono contenta ugualmente". Così all'Italpress Ina Casesa, la titolare della pasticceria Porretto, in via Luigi Galvani 51, a Palermo, dove è stato vinto il terzo premio della Lotteria Italia da 2 milioni di euro. "Siamo felicissimi, spero che la fortuna abbia baciato qualcuno che sia bisognoso, che si ricordi pure di noi", aggiunge. La pasticceria si trova nel quartiere Settecannoli ed è frequentata soprattutto da residenti della zona, dove è già partita la caccia al neo milionario. "Qui vengono clienti abitudinari, ma qualcuno di passaggio c'è sempre - spiega la titolare della pasticceria -. In questi giorni sono venute tante persone, molti amici, e di biglietti ne ho venduti tanti". "Spero che il vincitore si ricordi di noi - ribadisce -. Gli auguro il meglio della vita, che sappia gestire la vincita e tanta felicità, soprattutto se a vincere è stato un bisognoso". Quello vinto nella pasticceria della periferia palermitana è il terzo premio, serie G, numero 330068. xd8/vbo/gtr

Merriam-Webster's Word of the Day for December 8, 2024 is: galvanize • GAL-vuh-nyze • verb To galvanize people is to cause them to be so excited or concerned about something that they are driven to action. // The council's proposal to close the library has galvanized the town's residents. See the entry > Examples: “The original Earth Day was the product of a new environmental consciousness created by Rachel Carson's 1962 book, Silent Spring, and of public horror in 1969 that the Cuyahoga River in Ohio was so polluted it caught fire. … On April 22, 1970, some 20 million people attended thousands of events across America, and this galvanizing public demand led in short order to the creation, during Richard Nixon's presidency, of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970), the Clean Air Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), and the Endangered Species Act (1973), and much more after that.” — Todd Stern, The Atlantic, 6 Oct. 2024 Did you know? Luigi Galvani was an Italian physician and physicist who, in the 1770s, studied the electrical nature of nerve impulses by applying electrical stimulation to frogs' leg muscles, causing them to contract. Although Galvani's theory that animal tissue contained an innate electrical impulse was disproven, the French word galvanisme came to refer to a current of electricity especially when produced by chemical action, while the verb galvaniser was used for the action of applying such a current (both words were apparently coined by German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who modeled them after the French equivalents of magnetism and magnetize). In English, these words came to life as galvanism and galvanize, respectively. Today their primary senses are figurative: to galvanize a person or group is to spur them into action as if they've been jolted with electricity.

I 1780 satte den italienske læge Luigi Galvani strøm til en død frø og kunne fra dens spjættende lår konstatere, at livet er elektrisk. Siden da er vores viden om såkaldt bioelektricitet kun blevet dybere og mere raffineret. Elektriske ladninger strømmer gennem celler, væv, muskler og hjernedele i både menneske- og dyrekroppe. Flere hajer, fisk og sågar næbdyr har udviklet evnen til at sanse og udnytte elektriske felter omkring dem. Og på havets bund har forskere for nylig opdaget nogle forunderlige bakterier, der kan samle sig til kabelagtige superorganismer, som kan lede strøm. Hverken fysikken eller mikrobiologien kan endnu forklare kabelbakteriernes evne til at føre strøm, og selv kalder elektromikrobiologerne, der studerer dem de mærkværdige væsner for livsformen, som ingen havde forestillet sig. Samtidig har neurobiologer i dag fået en uhyre nuanceret forståelse for de komplekse måder, neuroner skaber forbindelser i vores hjerner og nervesystemer ved hjælp af elektrokemiske signaler. Men hvor forskellig er kabelbakteriernes strømføring i grunden fra processerne i komplekse organismers kroppe? Taler de besynderlige, flercellede havbundsorganismer samme sprog som cellerne i vores hjerner – eller er det en helt anden elektrisk forbundethed, der er på færde? Spids ører, når neurobiologen Jakob Balslev Sørensen og kabelbakterieforskeren Lars Peter Nielsen kaster lys over bioelektricitetens mystiske verden.

Frankenstein Reimagined: Bioelectricity and the Quest for Life Beyond Mechanism

Hello Interactors,A Frankenstein announcement from Musk this week punctuated my recent fascination with the author of that popular novel, Mary Shelley. Her isolated lived experience in a time of intense technological discovery, social and geo-political unrest, AND a climate crisis rings true today more than ever.But she also was subtlety representing a scientific movement that is largely ignored today, but just may be experiencing a bit of a resurgence in areas like biology and neuroscience.Let's dig in…FRANKEN-MUSK“It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.”Mary Shelley was intrigued, and maybe a little scared, by the idea of electrifying organs. She admits as much in her 1831 forward of her famous novel, “Frankenstein”, first published January 1, 1818. She wrote,"Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth."Bioelectrical experimentation had been happening for nearly 40 years by the time Shelley wrote this book. Luigi Galvani, an Italian physician, physicist, and philosopher demonstrated the existence of electricity in living tissue in the late 1780s. He called it ‘animal electricity'. Many repeated his experiments over the years and ‘galvanism' remained hotly debated well into the 1800s.I've been thinking a lot about Shelley and her “Frankenstein” lately. The hype and hysteria surrounding AI, human-like robots, and biocomputing make it easy to imagine. Just last week Elon Musk tweeted that his company, Neuralink, implanted its brain chip in a human for the first time. He wants to make ‘The Matrix' a reality. Here we are some 200 years later, wanting to believe ‘perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.'‘Vital warmth' seems a borrowed phrase from another scientific movement of the time, ‘vitalism'. Vitalism is the belief that living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities, like computer chips, because they are governed by a unique, non-physical force or "vital spark" that animates life. A kind of teleology for which some contemporary biologists now have empirical evidence.One prominent vitalist of the 18th and 19th century, the German physician, physiologist, and anthropologist, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, is best known for his contributions to the study of human biology. He developed the concept of the "Bildungstrieb" or "formative drive," which he proposed as an inherent force guiding the growth and development of organisms. Contemporary science explains these processes through a combination of genetic, biochemical, and physical principles like encoded DNA, gene expression networks, and morphogenesis — the interactions between cells and their responses to various chemical and mechanical forces.THE INDUSTRIALIST'S VITAL SPARK‘Formative drive' was a vitalist response to the mechanistic explanations of life that were prevalent in the Enlightenment period. The same mechanistic fervor that endues so many technologists today, like Musk, with vital warmth. Blumenbach argued that physical and chemical processes alone could not account for the organization and complexity of living beings. Instead, he suggested that some other vital force was responsible for the development and function of organic forms.Vitalists had their skeptics. Chiefly among them was Alessandro Volta. He was critical of Galvani's ‘vital spark'. In Galvani's frog leg experiments, he discovered that when two different metals (e.g., copper and zinc) were connected and then touched to a frog's nerve and muscle, the muscle would contract even without any external electrical source. Galvani concluded that this was due to an electrical force inherent in the nerves of the frog, a concept that challenged the prevailing views of the time and eventually laid the groundwork for the field of electrophysiology.Volta, however, believed the electrical effects were due to the metals used in Galvani's experiments. Volta's work eventually led to the development of the Voltaic Pile, an early form of a battery. Hence the term ‘volt'. The Voltaic Pile enabled a more systematic and controlled study of electricity, which was a relatively little-understood phenomenon at the time. It provided scientists and inventors with a consistent and reliable source of electrical energy for experiments, leading to a deeper understanding of electrical principles and the discovery of new technologies.One such technology was the invention of the telegraph in the 1830s. The availability of electric batteries as power sources is what made it possible for Samuel Morse to revolutionize long-distance communication, profoundly effecting commerce, governance, and daily life. As he wrote in his first public demonstration, “What hath God wrought?”The mechanists gained further favor as more and more scientists, inventors, and eventually economists succumbed to the allure of reductionism. They believed understanding complex phenomena could be done by studying their simplest, most fundamental, and mechanistic parts. Including body parts.ECHOES OF THE INDUSTRIAL AGEIt was around the time of Morse's tinkering that Mary Shelley reissued ‘Frankenstein'. She revealed in her 1831 forward how she was influenced by the scientific and philosophical ideas of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This included galvanism, the debates around vitalism, and the Romantic movement's reaction to the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason and science.This was also a period marked by significant political, social, and technological upheavals. The consolidation of nation-states and the expansion of political power were central themes of this era, leading to debates over government intervention and the balance between order and liberty. Shelley's narrative, set against this backdrop, can be seen as a reflection on the consequences of unchecked ambition and the ethical responsibilities of creators, themes that are increasingly relevant in today's discussions about artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and other forms of technological innovation.Moreover, Shelley's personal history and the socio-political context of her time deeply informed the themes of her novel. As the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, a pioneering feminist thinker, Shelley was exposed from an early age to, what were then, radical ideas about gender, society, and individual rights. Her own experiences of loss, isolation, and vulnerability were compounded by the societal upheavals of the Little Ice Age and the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. "Frankenstein" is imbued with a profound sense of existential questioning. It critiques the dehumanizing aspects of technological and industrial progress — themes that resonate with many today.Like the early parts of the Industrial Revolution, we are living in a period of transforming economies, social structures, and daily life, ushering in new forms of labor, consumption, and environmental impact. The creation of Shelley's ‘Creature' can be seen as a metaphor for the unforeseen consequences of industrialization, including the alienation of individuals from their labor, from nature, and from each other.Shelley's narrative warns of the dangers of valuing power and progress over empathy and ethical consideration, a warning that remains pertinent as society grapples with the implications of rapid technological advancement and environmental degradation. Mechanistic reductionism, with its emphasis on dissecting complex phenomena into their most basic parts, undeniably continues to dominate much of science, technology, and conventional thought.Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein," while serving as a cautionary tale about the hubris and potential perils of unchecked scientific and technological ambition, has paradoxically also fueled the collective imagination, inspiring generations to dream of creating a human-like entity from disparate parts and mechanisms.Yet, there is an emerging renaissance that harks back to the holistic perspectives reminiscent of early vitalism. As scientists increasingly traverse interdisciplinary boundaries, embracing the principles of holism and complexity science, they are uncovering new patterns, principles, and laws that echo the intuitions of early vitalists.The groundbreaking research of Michael Levin at Tufts University, with its focus on bioelectric patterns and their role in development and regeneration, offers a compelling empirical bridge to Blumenbach's ‘formative drive'. While Levin's work eschews the metaphysical aspects of a "life force," it uncovers the intricate bioelectric networks that guide the form and function of organisms, echoing vitalism's fascination with the organizing principles of life.This shift acknowledges that life's essence may not be fully captured by reductionist views alone. Levin shows how it's not the mechanisms of DNA that unlock the mysteries of biological organization but the communication between cells and their environment. It points towards a more integrated understanding of the natural world that respects the intricate interplay of its myriad components.Shelley's pondering remains relevant today, “perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth." Either way, "Frankenstein" continues to remind us of the need for humility and ethical consideration. After all, as we navigate the complex frontier between mechanistic ambition and our fragile, emergent, and interconnected life neurobiology tells us our own neural connections are being reshaped by both environmental interactions and cognitive activity, reflecting principles of embedded cognition those early vitalists would surely endorse. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit interplace.io

It's that time of year! SpooOOOoooOOOookey stories! First we talk about a hotbed of paranormal interdimensional activity in the heart of Mormon country; Skinwalker Ranch! After that we deep dive into the sci-fi classic Frankenstein. We wrap with a quick reminder to get out and vote along with catching up on listener mail! Show Notes: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_Burns https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Travis_S._Taylor https://www.linkedin.com/in/ecbard https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/Soil%20Electrical%20Conductivity.pdf https://www.reddit.com/r/sdr/comments/v4577h/16ghz_signals_a_simple_question_skinwalker/ https://www.utah.com/articles/post/what-is-skinwalker-ranch-and-whats-really-going-on-there https://www.iflscience.com/skinwalker-ranch-bastion-for-the-paranormal-or-hoax-69969 https://www.skeptic.com/reading_room/claims-about-pentagon-ufo-program-how-much-is-true/ https://www.hullingermortuary.com/obituaries/junior-hicks https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skinwalker_Ranch https://www.deseret.com/1996/6/30/19251541/frequent-fliers https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML2316/ML23165A245.pdf MOGP: Mary Shelley: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Shelley Percy Bysshe Shelley: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Percy_Bysshe_Shelley Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, by Mary Shelley: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankenstein Frankenstein Castle: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankenstein_Castle Luigi Galvani: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Galvani Giovanni Aldini: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Aldini Lord Byron: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Byron Happy News: Just get out and vote, y'all! Come see us on Aron Ra's YouTube channel! He's doing a series titled Reading Joseph's Myth BoM. This link is for the playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLXJ4dsU0oGMKfJKvEMeRn5ebpAggkoVHf Check out his channel here: https://www.youtube.com/@AronRa Email: glassboxpodcast@gmail.com Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/GlassBoxPod Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/glassboxpodcast Twitter: https://twitter.com/GlassBoxPod Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/glassboxpodcast/ Merch store: https://www.redbubble.com/people/exmoapparel/shop Or find the merch store by clicking on “Store” here: https://glassboxpodcast.com/index.html One time Paypal donation: bryceblankenagel@gmail.com

Cap 253: La Luz y Sombra de la Estimulación Magnética Transcraneal: ¿Promesa Médica o Controversia Científica?

Descubra la fascinante historia y las aplicaciones de la estimulación magnética transcraneal (EMT), una técnica de neuromodulación que utiliza campos magnéticos para alterar la actividad eléctrica del cerebro. Analice las raíces de esta tecnología, desde los primeros experimentos con electricidad de Luigi Galvani hasta las visiones electrificantes de la vida en la novela de Mary Shelley, "Frankenstein". Comprenda cómo la EMT ha evolucionado hasta convertirse en una herramienta potencialmente revolucionaria para tratar una variedad de trastornos neurológicos y psiquiátricos, desde la depresión hasta el dolor crónico. Discuta también las críticas y controversias en torno a la EMT, ya que no todos los estudios han encontrado beneficios claros y algunos argumentan que aún se necesita más investigación. En medio de este debate, los avances en nuestra comprensión del potencial de acción neuronal y su relación con la EMT ofrecen nuevas perspectivas. ¿Está preparado para sumergirse en este intrigante campo de la neurociencia y explorar su potencial para transformar la medicina y nuestro entendimiento del cerebro? Keywords: Estimulación Magnética Transcraneal, EMT, neurociencia, Galvani, Frankenstein, historia de la electricidad, potencial de acción, depresión, dolor crónico, trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo, neuromodulación, campos magnéticos, actividad cerebral, trastornos neurológicos, trastornos psiquiátricos, controversia EMT, investigación EMT, críticas EMT, estudios EMT, evolución EMT, corriente eléctrica, estímulo magnético, técnica de neuromodulación, potencial neuronal, neuroplasticidad. #EMT, #Neurociencia, #HistoriaDeLaElectricidad, #Galvani, #Frankenstein, #PotencialDeAccion "Electrificando el Cerebro: La Estimulación Magnética Transcraneal y su Potencial Revolucionario" "De Galvani a la EMT: Un Viaje Electrizante a través de la Historia de la Electricidad" "La Luz y Sombra de la EMT: ¿Promesa Médica o Controversia Científica?" "Desbloqueando el Potencial del Cerebro: ¿Es la EMT la Clave?" "El Potencial de Acción y la EMT: Comprendiendo la Neurociencia de la Estimulación Magnética Transcraneal" Links: 📘 Descubre nuestro nuevo libro: El Mapa de la Ansiedad 🌐 Conócenos más en nuestra Página Web 👍 Síguenos en Facebook 📸 Mantente al día en nuestro Instagram 🎥 Suscríbete a nuestro canal de Youtube Amadag TV

Episode: 2440 Johannes Georg Sulzer, and two views of the word taste. Today, taste in the mind and taste on the tongue.

"Spark: The Life of Electricity and the Electricity of Life" with Professor Timothy Jorgensen

When we think about electricity, we most often think of the energy that powers various devices and appliances around us, or perhaps we visualise the lightning-streaked clouds of a stormy sky. But there is more to electricity and “life at its essence is nothing if not electrical”. In this episode of Bridging the Gaps, I speak with Professor Timothy Jorgensen and we discuss his recent book “Spark: The Life of Electricity and the Electricity of Life ”. The book explains the science of electricity through the lenses of biology, medicine and history. It illustrates how our understanding of electricity and the neurological system evolved in parallel, using fascinating stories of scientists and personalities ranging from Benjamin Franklin to Elon Musk. It provides a fascinating look at electricity, how it works, and how it animates our lives from within and without. We start by discussing the earliest known experiences that humans had with electricity using amber. Amber was most likely the first material with which humans attempted to harness electricity, mostly for medical purposes. Romans used non-static electricity from specific types of fish. Moving on to Benjamin Franklin, we discuss how he attempted to harner the power of electricity and we discuss the earliest forms of devices to store electric charge. We then discuss experiments conducted by Luigi Galvani on dead frogs and by his nephew on dead humans using electricity. As interest in electricity grew, many so-called treatemnts for ailments such as headaches, for bad thoughts and even for sexual difficulties also emerged that were based on the use of electricity; we discuss few interesting examples of such treatments. We then move on to reviewing the cutting edge use of electricity in medical science and discussed medial implants, artificial limbs and deep stimulation technologies and proposed machine-brain interfaces. This has been a fascinating discussion. Complement this discussion by listening to "The Spike: Journey of Electric Signals in Brain from Perception to Action with Professor Mark Humphries" available at: https://www.bridgingthegaps.ie/2021/06/the-spike-journey-of-electric-signals-in-brain-from-perception-to-action-with-professor-mark-humphries/ And then listen to "On Public Communication of Science and Technology with Professor Bruce Lewenstein" available at: https://www.bridgingthegaps.ie/2022/02/on-public-communication-of-science-and-technology-with-professor-bruce-lewenstein/

Subscribe to Quotomania on Simplecast or search for Quotomania on your favorite podcast app!Mary Shelley is an English novelist whose work has reached all corners of the globe. Author of Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), Shelley was the daughter of the radical philosopher William Godwin, who described her as ‘singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind'. Her mother, who died days after her birth, was the famous defender of women's rights, Mary Wollstonecraft. Mary grew up with five semi-related siblings in Godwin's unconventional but intellectually electric household.At the age of 16, Mary eloped to Italy with the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who praised ‘the irresistible wildness & sublimity of her feelings'. Each encouraged the other's writing, and they married in 1816 after the suicide of Shelley's wife. They had several children, of whom only one survived. A ghost-writing contest on a stormy June night in 1816 inspired Frankenstein, often called the first true work of science-fiction. Superficially a Gothic novel, influenced by the experiments of Luigi Galvani, it was concerned with the destructive nature of power when allied to wealth. Familiar to scholars, librarians and the entire literary world, the novel tells the story of Doctor Victor Frankenstein and a creature he creates in an unorthodox scientific experiment. It was an instant wonder and spawned a mythology all of its own that endures to this day. After Percy Shelley's death in 1822, she returned to London and pursued a very successful writing career as a novelist, biographer and travel writer. She also edited and promoted her husband's poems and other writings.From https://www.bl.uk/people/mary-shelley. For more information about Mary Shelley:“Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley”: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/mary-wollstonecraft-shelley“The Strange and Twisted Life of ‘Frankenstein'”: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/02/12/the-strange-and-twisted-life-of-frankenstein“Frankenstein at 200”: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jan/13/frankenstein-at-200-why-hasnt-mary-shelley-been-given-the-respect-she-deserves-

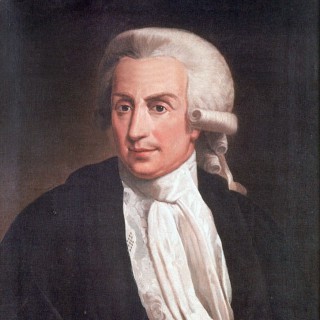

"Leggende - LUIGI GALVANI" In studio Silvia Parma ed Ettore Pancaldi

LEGGENDE - I GRANDI E LE GRANDI CHE HANNO FATTO GRANDE BOLOGNA

Un grande bolognese del passato, LUIGI GALVANI al quale si deve uno dei più grandi contributi della scienza moderna. In studio Silvia Parma ed Ettore Pancaldi

We've all heard the story of "Frankenstein's Monster." A bat shit crazy scientist wants to reanimate dead tissue and basically create a fucking zombie baby… BECAUSE THAT'S HOW YOU GET FUCKING ZOMBIES! Anyway, Dr. Frankenstein and his trusty assistant, Igor, set off to bring a bunch of random, dead body parts together, throw some lightning on the bugger and bring this new, puzzle piece of a quasi-human back to "life." At first, the reanimated corpse seems somewhat ordinary, but then flips his shit and starts terrorizing and doing what I can only imagine REANIMATED ZOMBIES FUCKING DO! Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in Somers Town, London, in 1797. She was the second child of the feminist philosopher, educator, and writer Mary Wollstonecraft and the first child of the philosopher, novelist, and journalist William Godwin. So, she was brought into this world by some smart fucking people. Mary's mother died of puerperal fever shortly after Mary was born. Puerperal fever is an infectious, sometimes fatal, disease of childbirth; until the mid-19th century, this dreaded, then-mysterious illness could sweep through a hospital maternity ward and kill most new mothers. Today strict aseptic hospital techniques have made the condition uncommon in most parts of the world, except in unusual circumstances such as illegally induced abortion. Her father, William, was left to bring up Mary and her older half-sister, Fanny Imlay, Mary's mother's child by the American speculator Gilbert Imlay. A year after her mother's death, Godwin published his Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which he intended as a sincere and compassionate tribute. However, the Memoirs revealed Mary's mother's affairs and her illegitimate child. In that period, they were seen as shocking. Mary read these memoirs and her mother's books and was brought up to cherish her mother's memory. Mary's earliest years were happy, judging from the letters of William's housekeeper and nurse, Louisa Jones. But Godwin was often deeply in debt; feeling that he could not raise Mary and Fanny himself, he looked for a second wife. In December 1801, he married Mary Jane Clairmont, a well-educated woman with two young children—Charles and Claire SO MANY MARY'S! Sorry folks. Most of her father's friends disliked his new wife, describing her as a straight fucking bitch. Ok, not really, but they didn't like her. However, William was devoted to her, and the marriage worked. Mary, however, came to hate that bitch. William's 19th-century biographer Charles Kegan Paul later suggested that Mrs. Godwin had favored her own children over Williams. So, how awesome is it that he had a biographer? That's so badass. Together, Mary's father and his new bride started a publishing firm called M. J. Godwin, which sold children's books and stationery, maps, and games. However, the business wasn't making any loot, and her father was forced to borrow butt loads of money to keep it going. He kept borrowing money to pay off earlier loans, just adding to his problems. By 1809, William's business was close to closing up shop, and he was "near to despair." Mary's father was saved from debtor's prison by devotees such as Francis Place, who lent him additional money. So, debtor's prison is pretty much EXACTLY what it sounds like. If you couldn't pay your debts, they threw your ass in jail. Unlike today where they just FUCK UP YOUR CREDIT! THANKS, COLUMBIA HOUSE!!! Though Mary received little education, her father tutored her in many subjects. He often took the children on educational trips. They had access to his library and the many intelligent mofos who visited him, including the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the former vice-president of the United States Aaron Burr. You know, that dude that shot and killed his POLITICAL opponent, Alexander Hamilton, in a fucking duel! Ah… I was born in the wrong century. Mary's father admitted he was not educating the children according to Mary's mother's philosophy as outlined in works such as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. However, Mary still received an unusual and advanced education for a girl of the time. She had a governess, a daily tutor, and read many of her father's children's Roman and Greek history books. For six months in 1811, she also attended a boarding school in Ramsgate, England. Her father described her at age 15 as "singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire of knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes almost invincible." My father didn't know how to spell my name until I was twelve. In June of 1812, Mary's father sent her to stay with the family of the radical William Baxter, near Dundee, Scotland. In a letter to Baxter, he wrote, "I am anxious that she should be brought up ... like a philosopher, even like a cynic." Scholars have speculated that she may have been sent away for her health, remove her from the seamy side of the business, or introduce her to radical politics. However, Mary loved the spacious surroundings of Baxter's house and with his four daughters, and she returned north in the summer of 1813 to hang out for 10 months. In the 1831 introduction to Frankenstein, she recalled: "I wrote then—but in a most common-place style. It was beneath the trees of the grounds belonging to our house, or on the bleak sides of the woodless mountains near, that my true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered." Mary Godwin may have first met the radical poet-philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley in between her two stays in Scotland. When she returned home for a second time on 30 March 1814, Percy Shelley became estranged from his wife and regularly visited Mary's father, William Godwin, whom he had agreed to bail out of debt. Percy Shelley's radicalism, particularly his economic views, alienated him from his wealthy aristocratic family. They wanted him to be a high, upstanding snoot and follow traditional models of the landed aristocracy. He tried to donate large amounts of the family's money to projects meant to help the poor and disadvantaged. Percy Shelley, therefore, had a problem gaining access to capital until he inherited his estate because his family did not want him wasting it on projects of "political justice." After several months of promises, Shelley announced that he could not or would not pay off all of Godwin's debts. Godwin was angry and felt betrayed and whooped his fuckin ass! Yeah! Ok, not really. He was just super pissed. Mary and Percy began hookin' up on the down-low at her mother Mary Wollstonecraft's grave in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church, and they fell in love—she was 16, and he was 21. Creepy and super fucking gross. On 26 June 1814, Shelley and Godwin declared their love for one another as Shelley announced he could not hide his "ardent passion,." This led her in a "sublime and rapturous moment" to say she felt the same way; on either that day or the next, Godwin lost her virginity to Shelley, which tradition claims happened in the churchyard. So, the grown-ass 21-year-old man statutorily raped the 16-year-old daughter of the man he idolized and dicked over. In a graveyard. My god, how things have changed...GROSS! Godwin described herself as attracted to Shelley's "wild, intellectual, unearthly looks." Smart but ugly. Got it. To Mary's dismay, her father disapproved and tried to thwart the relationship and salvage his daughter's "spotless fame." No! You don't say! Dad wasn't into his TEENAGE DAUGHTER BANGING A MAN IN THE GRAVEYARD!?! Mary's father learned of Shelley's inability to pay off the father's debts at about the same time. Oof. He found out after he diddled her. Mary, who later wrote of "my excessive and romantic attachment to my father," was confused. Um… what? She saw Percy Shelley as an embodiment of her parents' liberal and reformist ideas of the 1790s, particularly Godwin's view that marriage was a repressive monopoly, which he had argued in his 1793 edition of Political Justice but later retracted. On 28 July 1814, the couple eloped and secretly left for France, taking Mary's stepsister, Claire Clairmont, with them. After convincing Mary's mother, who took off after them to Calais, that they did not wish to return, the trio traveled to Paris, and then, by donkey, mule, carriage, and foot, through France, recently ravaged by war, all the way to Switzerland. "It was acting in a novel, being an incarnate romance," Mary Shelley recalled in 1826. Godwin wrote about France in 1814: "The distress of the inhabitants, whose houses had been burned, their cattle killed and all their wealth destroyed, has given a sting to my detestation of war...". As they traveled, Mary and Percy read works by Mary Wollstonecraft and others, kept a joint journal, and continued their own writing. Finally, at Lucerne, lack of money forced the three to turn back. Instead, they traveled down the Rhine and by land to the Dutch port of Maassluis, arriving at Gravesend, Kent, on 13 September 1814. The situation awaiting Mary Godwin in England was packed with bullshit, some of which she had not expected. Either before or during their journey, she had become pregnant. She and Percy now found themselves penniless, and, to Mary's stupid ass surprise, her father refused to have anything to do with her. The couple moved with Claire into lodgings at Somers Town, and later, Nelson Square. They kept doing their thing, reading, and writing and entertained Percy Shelley's friends. Percy Shelley would often leave home for short periods to dodge bill collectors, and the couple's heartbroken letters would reveal their pain while he was away. Pregnant and often sick, Mary Godwin had to hear of Percy's joy at the birth of his son by Harriet Shelley in late 1814 due to his constant escapades with Claire Clairmont. Supposedly, Shelley and Clairmont were almost certainly lovers, which caused Mary to be rightfully jealous. And yes, Claire was Mary's cousin. Percy was a friggin' creep. Percy pissed off Mary when he suggested that they both take the plunge into a stream naked during a walk in the French countryside. This offended her due to her principles, and she was like, "Oh, hell nah, sahn!" and started taking off her earrings in a rage. Or something like that. She was partly consoled by the visits of Hogg, whom she disliked at first but soon considered a close friend. Percy Shelley seems to have wanted Mary and Hogg to become lovers; Mary did not dismiss the idea since she believed in free love in principle. She was a hippie before being a hippie was cool. Percy probably just wanted to not feel guilty for hooking up with her cousin. Creep. In reality, however, she loved only Percy and seemed to have gone no further than flirting with Hogg. On 22 February 1815, she gave birth to a two-months premature baby girl, who was not expected to survive. On 6 March, she wrote to Hogg: "My dearest Hogg, my baby is dead—will you come to see me as soon as you can. I wish to see you—It was perfectly well when I went to bed—I awoke in the night to give it suck it appeared to be sleeping so quietly that I would not awake it. It was dead then, but we did not find that out till morning—from its appearance it evidently died of convulsions—Will you come—you are so calm a creature & Shelley (Percy) is afraid of a fever from the milk—for I am no longer a mother now." The loss of her child brought about acute depression in Mary. She was haunted by visions of the baby, but she conceived again and had recovered by the summer. With a revival in Percy's finances after the death of his grandfather, Sir Bysshe Shelley, the couple holidayed in Torquay and then rented a two-story cottage at Bishopsgate, on the edge of Windsor Great Park. Unfortunately, little is known about this period in Mary Godwin's life since her journal from May 1815 to July 1816 was lost. At Bishopsgate, Percy wrote his poem Alastor or The Spirit of Solitude; and on 24 January 1816, Mary gave birth to a second child, William, named after her father and soon nicknamed "Willmouse." In her novel The Last Man, she later imagined Windsor as a Garden of Eden. In May 1816, Mary, Percy, and their son traveled to Geneva with Claire Clairmont. They planned to spend the summer with the poet Lord Byron, whose recent affair with Claire had left her pregnant. Claire sounds like a bit of a trollop. No judging, just making an observation. The party arrived in Geneva on 14 May 1816, where Mary called herself "Mrs Shelley." Byron joined them on 25 May with his young physician, John William Polidori, and rented the Villa Diodati, close to Lake Geneva at the village of Cologny; Percy rented a smaller building called Maison Chapuis on the waterfront nearby. They spent their time writing, boating on the lake, and talking late into the night. "It proved a wet, ungenial summer," Mary Shelley remembered in 1831, "and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house." Sitting around a log fire at Byron's villa, the company amused themselves with German ghost stories called Fantasmagoriana, which prompted Byron to propose that they "each write a ghost story." Unable to think up an account, young Mary became flustered: "Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative." Finally, one mid-June evening, the discussions turned to the principle of life. "Perhaps a corpse would be reanimated," Mary noted, "galvanism had given token of such things." Galvanism is a term invented by the late 18th-century physicist and chemist Alessandro Volta to refer to the generation of electric current by chemical action. The word also came to refer to the discoveries of its namesake, Luigi Galvani, specifically the generation of electric current within biological organisms and the contraction/convulsion of natural muscle tissue upon contact with electric current. While Volta theorized and later demonstrated the phenomenon of his "Galvanism" to be replicable with otherwise inert materials, Galvani thought his discovery to confirm the existence of "animal electricity," a vital force that gave life to organic matter. We'll talk a little more about Galvani and a murderer named George Foster toward the end of the episode. It was after midnight before they retired, and she was unable to sleep, mainly because she became overwhelmed by her imagination as she kept thinking about the grim terrors of her "waking dream," her ghost story: "I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world." She began writing what she assumed would be a short, profound story. With Percy Shelley's encouragement, she turned her little idea into her first novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, published in 1818. She later described that time in Switzerland as "when I first stepped out from childhood into life." The story of the writing of Frankenstein has been fictionalized repeatedly, and it helped form the basis for several films. Here's a cool little side note: In September 2011, the astronomer Donald Olson, after a visit to the Lake Geneva villa the previous year and inspecting data about the motion of the moon and stars, concluded that her waking dream took place "between 2 am and 3 am" 16 June 1816, several days after the initial idea by Lord Byron that they each write their ghost stories. Shelley and her husband collaborated on the story, but the extent of Percy's contribution to the novel is unknown and has been argued over by readers and critics forever. There are differences in the 1818, 1823, and 1831 versions. Mary Shelley wrote, "I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband, and yet but for his incitement, it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world." She wrote that the preface to the first edition was her husband's work "as far as I can recollect." James Rieger concluded Percy's "assistance at every point in the book's manufacture was so extensive that one hardly knows whether to regard him as editor or minor collaborator." At the same time, Anne K. Mellor later argued Percy only "made many technical corrections and several times clarified the narrative and thematic continuity of the text." Charles E. Robinson, the editor of a facsimile edition of the Frankenstein manuscripts, concluded that Percy's contributions to the book "were no more than what most publishers' editors have provided new (or old) authors or, in fact, what colleagues have provided to each other after reading each other's works in progress." So, eat one, Percy! Just kidding. In 1840 and 1842, Mary and her son traveled together all over the continent. Mary recorded these trips in Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842, and 1843. In 1844, Sir Timothy Shelley finally died at the age of ninety, "falling from the stalk like an overblown flower," Mary put it. For the first time in her life, she and her son were financially independent, though the remaining estate wasn't worth as much as they had thought. In the mid-1840s, Mary Shelley found herself in the crosshairs of three separate blackmailing sons of bitches. First, in 1845, an Italian political exile called Gatteschi, whom she had met in Paris, threatened to publish letters she had sent him. Scandalous! However, a friend of her son's bribed a police chief into seizing Gatteschi's papers, including the letters, which were then destroyed. Vaffanculo, Gatteschi! Shortly afterward, Mary Shelley bought some letters written by herself and Percy Shelley from a man calling himself G. Byron and posing as the illegitimate son of the late Lord Byron. Also, in 1845, Percy Shelley's cousin Thomas Medwin approached her, claiming to have written a damaging biography of Percy Shelley. He said he would suppress it in return for £250, but Mary told him to eat a big ole bag of dicks and jog on! In 1848, Percy Florence married Jane Gibson St John. The marriage proved a happy one, and Mary liked Jane. Mary lived with her son and daughter-in-law at Field Place, Sussex, the Shelleys' ancestral home, and at Chester Square, London, and vacationed with them, as well. Mary's last years were blighted by illness. From 1839, she suffered from headaches and bouts of paralysis in parts of her body, which sometimes prevented her from reading and writing, obviously two of her favorite things. Then, on 1 February 1851, at Chester Square, Mary Shelly died at fifty-three from what her doctor suspected was a brain tumor. According to Jane Shelley, Mary had asked to be buried with her mother and father. Still, looking at the graveyard at St Pancras and calling it "dreadful," Percy and Jane chose to bury her instead at St Peter's Church in Bournemouth, near their new home at Boscombe. On the first anniversary of Mary's death, the Shelleys opened her box-desk. Inside they found locks of her dead children's hair, a notebook she had shared with Percy Bysshe Shelley, and a copy of his poem Adonaïs with one page folded round a silk parcel containing some of his ashes and the remains of his heart. Romantic or disturbing? Maybe a bit of both. Mary Shelley remained a stout political radical throughout her life. Mary's works often suggested that cooperation and sympathy, mainly as practiced by women in the family, were the ways to reform civil society. This view directly challenged the individualistic Romantic ethos promoted by Percy Shelley and Enlightenment political theories. She wrote seven novels / Two travel narrations / Twenty three short stories / Three books of children's literature, and many articles. Mary Shelley left her mark on the literary world, and her name will be forever etched in the catacombs of horror for generations to come. When it comes to reanimation, there's someone else we need to talk about. George Forster (or Foster) was found guilty of murdering his wife and child by drowning them in Paddington Canal, London. He was hanged at Newgate on 18 January 1803, after which his body was taken to a nearby house where it was used in an experiment by Italian scientist Giovanni Aldini. At his trial, the events were reconstructed. Forster's mother-in-law recounted that her daughter and grandchild had left her house to see Forster at 4 pm on Saturday, 4 December 1802. In whose house Forster lodged, Joseph Bradfield reported that they had stayed together that night and gone out at 10 am on Sunday morning. He also stated that Forster and his wife had not been on good terms because she wished to live with him. On Sunday, various witnesses saw Forster with his wife and child in public houses near Paddington Canal. The body of his child was found on Monday morning; after the canal was dragged for three days, his wife's body was also found. Forster claimed that upon leaving The Mitre, he set out alone for Barnet to see his other two children in the workhouse there, though he was forced to turn back at Whetstone due to the failing light. This was contradicted by a waiter at The Mitre who said the three left the inn together. Skepticism was also expressed that he could have walked to Whetstone when he claimed. Nevertheless, the jury found him guilty. He was sentenced to death and also to be dissected after that. This sentence was designed to provide medicine with corpses on which to experiment and ensure that the condemned could not rise on Judgement Day, their bodies having been cut into pieces and selectively discarded. Forster was hanged on 18 January, shortly before he made a full confession. He said he had come to hate his wife and had twice before taken his wife to the canal, but his nerve had both times failed him. A recent BBC Knowledge documentary (Real Horror: Frankenstein) questions the fairness of the trial. It notes that friends of George Forster's wife later claimed that she was highly suicidal and had often talked about killing herself and her daughter. According to this documentary, Forster attempted suicide by stabbing himself with a crudely fashioned knife. This was to avoid awakening during the dissection of his body, should he not have died when hanged. This was a real possibility owing to the crude methods of execution at the time. The same reference suggests that his 'confession' was obtained under duress. In fact, it alleges that Pass, a Beadle or an official of a church or synagogue on Aldini's payroll, fast-tracked the whole trial and legal procedure to obtain the freshest corpse possible for his benefactor. After the execution, Forster's body was given to Giovanni Aldini for experimentation. Aldini was the nephew of fellow scientist Luigi Galvani and an enthusiastic proponent of his uncle's method of stimulating muscles with electric current, known as Galvanism. The experiment he performed on Forster's body demonstrated this technique. The Newgate Calendar (a record of executions at Newgate) reports that "On the first application of the process to the face, the jaws of the deceased criminal began to quiver, and the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion." Several people present believed that Forster was being brought back to life (The Newgate Calendar reports that even if this had been so, he would have been re-executed since his sentence was to "hang until he be dead"). One man, Mr. Pass, the beadle of the Surgeons' Company, was so shocked that he died shortly after leaving. The hanged man was undoubtedly dead since his blood had been drained and his spinal cord severed after the execution. Top Ten Frankenstein Movies https://screenrant.com/best-frankenstein-movies-ranked-imdb/

Merriam-Webster's Word of the Day for December 3, 2021 is: galvanize • GAL-vuh-nyze • verb Galvanize means "to cause (people) to take action on something that they are excited or concerned about." // The council's proposal to close the library has galvanized the town's residents. See the entry > Examples: "I think circumstances we've been through helped get us to this point. Whether it is the natural disaster, the pandemic or some of the tough losses … all of it helped galvanize this team." — Dwain Jenkins, quoted in The Advocate (Louisiana), 19 Oct. 2021 Did you know? Luigi Galvani was an Italian physician and physicist who, in the 1770s, studied the electrical nature of nerve impulses by applying electrical stimulation to frogs' leg muscles, causing them to contract. Although Galvani's theory that animal tissue contained an innate electrical impulse was disproven, the French word galvanisme came to describe a current of electricity especially when produced by chemical action. English borrowed the word as galvanism, and shortly after the verb galvanize came to life.

Aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, les travaux de Luigi Galvani et Alessandro Volta sur l'électricité permettent d'en mieux comprendre les mécanismes. Ils débouchent également sur le "galvanisme", dont l'un des buts n'était rien de moins que de ressusciter des cadavres !Des expériences sur l'électricitéComme tous les naturalistes de cette fin du XVIIIe siècle, l'anatomiste Luigi Galvani a l'habitude de disséquer des grenouilles pour mieux comprendre certains mécanismes corporels.Au cours de l'une de ces expériences, il place la patte du batracien, qui est reliée à un crochet de cuivre, sur un objet métallique. En touchant la patte de la grenouille, il s'aperçoit qu'elle est agitée de vives contractions.Il est persuadé qu'il vient de démontrer, par hasard, l'existence de l'électricité animale. Mais, pour le physicien Alessandro Volta, cette électricité ne provient pas de la grenouille.Elle est produite par le contact entre deux métaux, le cuivre du crochet et le fer de l'objet sur lequel la grenouille a été déposée. En 1800, pour prouver que la source de l'électricité est bien métallique, il confectionne une pile. Autrement dit des disques de métal empilés les uns sur les autres, qui produisent bien de l'électricité.Une tentative pour ressusciter les mortsCes expériences sur l'électricité font germer une idée, a priori saugrenue, dans l'esprit de certains scientifiques. Si une décharge électrique peut provoquer des contractions musculaires, ne peut-on utiliser cette technique pour ranimer un mort ?Aussitôt dit aussitôt fait. Ainsi, un scientifique italien, Giovanni Aldini obtient l'autorisation de faire une expérience sur des condamnés à la décapitation. On pensait en effet que, pour être efficace, la méthode du "galvanisme" devait s'appliquer sur des cadavres encore chauds.Aldini place alors deux fils métalliques dans les oreilles du supplicié, reliés à une pile. La tête s'anime alors de contractions qui s'emparent des muscles du visage, formant de sinistres grimaces.La même expérience, mais sur un cadavre de pendu, entraîne des contractions dans tout le corps. Le galvanisme suscite l'engouement du public, mais, contrairement aux attentes, il ne ramène pas les cadavres à la vie. See acast.com/privacy for privacy and opt-out information.

Luigi Galvani - The Modern Dr. Frankenstein

Luigi Galvani was one of the Enlightenment's brightest medical minds. His experiments challenged people to consider the nature of existence and might have been so influential that they contributed to the end of the Enlightenment.