Podcasts about aragonese

- 33PODCASTS

- 43EPISODES

- 43mAVG DURATION

- 1MONTHLY NEW EPISODE

- Aug 11, 2025LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about aragonese

Latest news about aragonese

- Sijena Murals Spark Protest as Aragon Team Begins Inspection ARTnews.com - Jul 28, 2025

- Aljaferia Palace in Zaragoza, Spain Atlas Obscura - Jan 24, 2025

- Loren Goldner - The Spanish Revolution, Past and Future: Grandeur and Poverty of Anarchism The Anarchist Library - Jul 2, 2024

- The Sorrows Of Empire – OpEd Eurasia Review - Jun 15, 2024

- Daily Prayers with Decomposing Corpses: Death Chairs at Aragonese Castle Ancient Origins - May 23, 2024

- Getting to know Juan Pablo Martínez: A Q&A with an Aragonese language activist Global Voices - May 3, 2024

- Catalonia’s Independence Struggle Has Deep Roots Jacobin - Feb 22, 2023

Latest podcast episodes about aragonese

The hurdy-gurdy is a string instrument that produces sound by means of a hand-cranked rosined wheel which rubs against the strings. The wheel functions much like a violin bow, and single notes played on the instrument sound similar to those of a violin. Most hurdy-gurdies have multiple drone strings, which give a constant pitch accompaniment to the melody, resulting in a sound similar to that of bagpipes. It is mostly used in Occitan, Aragonese, Cajun French, Asturian, Cantabrian, Galician, Hungarian, and Slavic folk music. It can also be seen in early music settings such as medieval, renaissance or baroque music.Sonic's Friendly Nemesis Knuckles #100:00 Intro06:02 Rites of Passage! Part 142:47 Outro-----Gotta Talk Fast is an oral review of Archie Comics' Sonic the Hedgehog. Way past cool.LINKS: https://gottatalkfast.com/

Iberia, 1809: the Aragonese capital of Zaragoza was under siege once again. To the west, the French prepared another invasion of Portugal. Meanwhile, in London, the British leadership debated a renewed commitment in this theater of the war. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Please Follow us on: Instagram Facebook Kimberly and Tommaso share their experiences on the island of Ischia, near Napoli, Italy. They discuss Ischia's geography, history, cuisine, beaches and the island's appeal. Key Points: Initial Impressions of Ischia: Kimberly revisits Ischia after 30 years since her last visit, noting its idyllic scenery and vibrant colors. Tommaso recalls having the best pizza of his life upon arrival. Ischia is relatively small, about 46 square kilometers, yet offers diverse landscapes. Geography and Driving Challenges: The island has one main ring road, making travel slow due to curves and narrow roads. Driving can be difficult due to log jams caused by buses and parked cars. Kimberly and Tommaso canceled their rental car after one day due to the intense driving conditions. Historical and Geographical Makeup: Ischia is a volcanic island with fertile soil, home to diverse Mediterranean plants. The island was first inhabited by Greeks in the 8th century B.C. The Aragonese castle, built in 474 B.C., is a significant historical site. Tourism and Local Life: Ischia has a population of 60,000 residents and attracts 6 million tourists annually. The island offers a variety of accommodations from resorts to hotels in condensed villages. The cuisine is seafood-heavy, with excellent pizza and salads. Beaches and Weather: Ischia boasts sandy beaches, a unique feature compared to other islands like Capri. The island's beaches are a major draw for mainland Italians. Tommaso provides a weather update, noting the extreme heat in Italy and warmer-than-usual Mediterranean temperatures. They advise listeners to stay hydrated and prepared for the heat. Next Episode: Kimberly and Tommaso will share the challenging but funny driving experience, as well their very interesting visit to the Aragonese Castle and luxurious day at a beach club.

Fluent Fiction - Catalan: The Ultimate Tapas Debate in Barcelona's Heart Find the full episode transcript, vocabulary words, and more:fluentfiction.org/the-ultimate-tapas-debate-in-barcelonas-heart Story Transcript:Ca: En el punt més escaldat de Barcelona, sota un sol que semblava espargir quèlsia dins del tòrax de qui oseixi sortir a l'exterior, Marta i Jordi havien trobat un racó d'ombra sota l'ala protectora d'un restaurant que regalava promeses de tapes delicioses i cervesa molt freda.En: In the hottest spot of Barcelona, under a sun that seemed to be dispersing chaos inside the chest of anyone daring to go outside, Marta and Jordi had found a shady corner under the protective wing of a restaurant that promised delicious tapas and very cold beer.Ca: Tot plegat comptava com un màgic parèntesi en la joiosa feinada de la ciutat, amb les fulles que semblaven ballar tan ricament sobre les pedres centenàries de la plaça, i una família de turistes italians que buscaven amb mà estratègica el millor àngel per la seva foto.En: All of it felt like a magical parenthesis in the joyful hustle and bustle of the city, with leaves appearing to dance so richly on the ancient stones of the square, and a family of Italian tourists strategically seeking the best angle for their photo.Ca: Marta, amb el seu cabell de foc, pujada al petit balancí del banc on estaven asseguts, i Jordi, un cop esvelt amb una mirada que destil·lava una dolçura indomable, debatien amb passió qui era el veritable inventor de les patates braves, el plat eminent que ara tots dos compartien.En: Marta, with her fiery hair, perched on the small swing of the bench where they were sitting, and Jordi, tall and slender with a gaze that exuded an untamed sweetness, passionately debated who was the true inventor of patatas bravas, the eminent dish they were both now sharing.Ca: - És aragonès, te l'asseguro - insistia Marta, amb un boci de patata penjant de la forqueta.En: - It's Aragonese, I assure you - Marta insisted, with a piece of potato hanging from her fork.Ca: - No puc creure que encara estiguis debatent això, Marta. És un plat absolutament madrileny! - es reia Jordi, els ulls brillant de diversió.En: - I can't believe you're still debating this, Marta. It's absolutely a dish from Madrid! - Jordi laughed, his eyes gleaming with amusement.Ca: El conflicte, tan suau com el vinagre Chardonnay que compartien, es va encendre amigablement mentre es perdia en la cacofonia de la plaça.En: The conflict, as gentle as the Chardonnay vinegar they shared, ignited amicably as it got lost in the cacophony of the square.Ca: Es van debatre molt, i entre rialles i clars desacords, va arribar un moment de pau. Una dona gran, amb una gran capsa plena d'especies exòtiques i amb una sabidoria tradicional esculpida a la seva cara, es va acostar a la seva taula. Van parlar una estona, i finalment, amb un somriure màgic, els va revelar la resposta.En: They debated a lot, and amidst laughter and clear disagreements, a moment of peace arrived. An elderly woman, with a large box full of exotic spices and traditional wisdom carved into her face, approached their table. They talked for a while, and finally, with a magical smile, she revealed the answer to them.Ca: Els ulls de Marta i Jordi es van obert de par en par. Ambdues teories estaven equivocades. Els ho havia dit de manera tan convincent, recolzant-se en anècdotes i fets històrics, que no van tenir més remei que acceptar-ho. La veritat era que les patates braves eren originàries de... Barcelona.En: Marta and Jordi's eyes widened. Both theories were wrong. She had told them in such a convincing way, backed by anecdotes and historical facts, that they had no choice but to accept it. The truth was that patatas bravas originated from... Barcelona.Ca: Amb aquesta revelació, van romandre en silenci uns pocs segons, fins que es van mirar l'un a l'altre i van esclatar en una rialla ressonant, compartint un altre got de cervesa i acabant-se les últimes tapes.En: With this revelation, they remained silent for a few seconds, until they looked at each other and burst into a resounding laughter, sharing another glass of beer and finishing the last tapas.Ca: Finalment, la tarda va arribar a la seva conclusió, i Marta i Jordi, amb les seves cares lluminoses, es van aixecar del banc. Es van mirar l'un a l'altre, somrients, sabent que havien compartit un moment divertit i especial, una conversa que no oblidarien mai, tot això, enmig del cor palpitant de Barcelona. Després de tot, més que una disputa sobre la invenció de alguna cosa, el que realment importava era el vincle que s'havia creat entre ells mentre compartien aquell plat de tapes.En: Finally, the afternoon came to its conclusion, and Marta and Jordi, with their bright faces, stood up from the bench. They looked at each other, smiling, knowing that they had shared a fun and special moment, a conversation they would never forget, all in the midst of the pulsating heart of Barcelona. After all, more than a dispute about the invention of something, what really mattered was the bond that had been created between them while sharing that plate of tapas. Vocabulary Words:hottest: escaldatspot: puntsun: solchaos: quèlsiachest: tòraxdaring: oseixishady: ombraprotective: protectorarestaurant: restaurantdelicious: deliciosescold: fredabeer: cervesamagical: màgicjoyful: joiosaancient: centenàriessquare: plaçafamily: famíliaItalian: italianstourists: turistesbest: millorphoto: fotofiery: focswing: balancíbench: banctall: altslender: esveltgaze: miradaexuded: destil·lavauntamed: indomable

Enrique Granados - Aragonese RhapsodyDouglas Riva, pianoMore info about today's track: Naxos 8.554629Courtesy of Naxos of America Inc.SubscribeYou can subscribe to this podcast in Apple Podcasts, or by using the Daily Download podcast RSS feed.Purchase this recordingAmazon

History Hack: Imprisoned Queens in Aragonese Controlled Mallorca

Jessica Minieri joins us to talk about Medieval history and more about two lesser known Aragonese Queens during that time. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

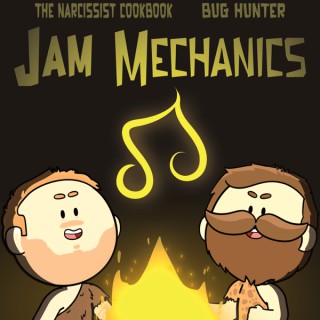

On our first episode of Jam Mechanics, we break the ice, introduce ourselves, and tell one of our favorite tour stories. Bug and Matt challenge each other to write a brand new song (from scratch!) in a three-hour window. Jam Mechanics is a podcast hosted by Matt (The Narcissist Cookbook) and Bug (Bug Hunter) where we challenge each other to write a song demo from scratch every episode. If you'd like downloadable files for this episode (and the demos we showed off), you can go to our Bandcamp or website to pay-what-you-want to support us! Our Music: The Narcissist Cookbook Bug Hunter Feel free to reach out to us at: Both: hello@jammechanics.com Bug: bug@jammechanics.com Matt: tnc@jammechanics.com and follow us on Instagram, Tumblr, YouTube, and Spotify! Please share the show (and our music) with friends! -- SPOILERS FOR THIS EPISODE BELOW -- MATT'S SONG Bug's Challenge: Write a song about the four elements. Cannot use the words: Fire, Water, Wind, Earth, Hot, Wet, Wind, Dirt Title: The World Yet to Come Lyrics: grab my winter coat and leave the door unlocked I'll be back before you know I'm gone cutting through the sidestreets with the alleycats and missing dogs whispers from the reservoir have kept me up buzzing lights impersonate the sun missives from the landfill to the west of town frozen condensation in my lungs and I will be back when the spell is cast I'll breeze through your door with my heart intact the crystals that form on the inside of our windows will fracture and come apart I'm waiting I'm waiting for sun the life of the world yet to come --------------------- BUG'S SONG Matt's challenge: Write a song about this (random) Wikipedia page Title: Francesco Lyrics: Franceso is the mayor of a city by the shore its on the southern tip of Italy known for tuna fish and tourists he books a meeting, sends an email, poses for the local paper one more email, has that meeting, off to dinner with his neighbors that's Francesco Francesco, he was named after a saint called Padre Pio who reportedly fought demons, claimed he parlato con dio He says a prayer, goes to mass, and poses with a little wafer one more prayer, one more sip of wine then pranzo with his neighbors that's Francesco And though he's not producing miracles or guiding wayward spirits homes I wonder if Francesco thinks about it yeah, I wonder if Francesco thinks about it. But in March of 241 BC the Roman and Phoenician Fleets began a battle in the sea just off the coast of Sicily So many bodies on the beach, they turned it red, now theirs to keep they built a tower on the hill, passed back and forth through history The Romans and Aragonese, the Normans and the Genoese but now it's ruled by Angelo who runs the gift shop at its feet and now I think about that abandoned fort the bodies stacked on that bloody shore how long it took to clear the port 2000 years of tug of war Now long after the Fall of Rome An office chair usurps the throne A modern mayor scrawls his name on permits for a loading zone It hasn't always been this way it hasn't always been this way and I wonder if Francesco thinks about it yeah I wonder if Francesco thinks about it --- Send in a voice message: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/jammechanicspodcast/message

Special Feature: RSJ Special Issue on Iberian Household's (IN SPANISH!)

This very special episode features Diana Pelaz Flores, guest editor of the current Royal Studies Journal special issue 'The Iberian Queen's Households: Dynamics, Social Strategies and Royal Power' (Vol 10.1, June 2023). Diana is the 'host' of this episode, in conversation with Lledó Ruiz Domingo and Paula Del Val Vales, who both contributed articles to this issue. We are delighted to have this episode in Spanish--a first for the Royal Studies Podcast!Please note: We are aware that there are some minor issues with the audio which could not be completely addressed in the mastering of the episode. We apologise for the less than ideal audio but we hope you will still enjoy listening to this feature.Information about our guests:Diana Pelaz Flores is Senior Lecturer in the Medieval History at the University of Santiago de Compostela. She was the main researcher of the project “Court feminine spaces: Curial areas, territorial relations and political practices”, granted by the Spanish Government, integrated within the MUNARQAS coordinated project, under the direction by Angela Munoz Fernandez. Her research examined the history of women and power, in particular the Queens consort of the Crown of Castile during the Late Middle Ages. She has several publications, including Rituales Líquidos. El significado del agua en el ceremonial de la Corte de Castilla (ss. XIV-XV) (Murcia: Universidad de Murcia, 2017), La Casa de la Reina en la Corona de Castilla (1418-1496) (Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, 2017), Poder y representación de la reina en la Corona de Castilla (1418-1496) (Ávila: Junta de Castilla y León, 2017), and Reinas Consortes. Las reinas de Castilla en la Edad Media (siglos XI-XV) (Madrid: Sílex, 2017)).Dr. Lledó Ruiz Domingo is postdoctoral researcher of Late Medieval Iberian Queenship at the University of Lisbon (Portugal) and University of Valencia (Spain). Her wider interests focus on political activity of Aragonese consort as co-rulers and partners with their royal husbands, especially during their periods as Lieutenant, using all the King's powers and authority. She has also focused her analysis on the Queens' economic resources during the Late Middle Ages. In this sense, she has published a monography “El tresor de la Reina” about the patrimony, income and expenditure of the Aragonese Queens.Paula Del Val Vales is a third year PhD student and Associate Lecturer at the University of Lincoln, where she develops her thesis ‘The Queen's Household in the Thirteenth Century: A Comparative Anglo-Iberian Study'. Paula is a Postgraduate Fellow Abroad as her PhD is funded by the La Caixa Foundation, and a member of the research group MUNARQAS. Paula has been on placement at the British Library, within the digitisation project 'Medieval and Renaissance Women', focused on digitising more than 300 documents related to medieval and renaissance women (1100-1600). Through her research she aims to explore the queens' establishments, resources, revenues, personnel and networks. She is also working on the first ever critical edition of the household and wardrobe accounts of Eleanor of Provence.

"La Madriguera", la obra ganadora del Premio Pulitzer que tiene a Nathalia Aragonese como protagonista

La actriz Nathalia Aragonese entregó detalles en Una Nueva Mañana acerca de "La Madriguera", una obra de teatro estrenada en Broadway que, incluso ha ganado un Premio Pulitzer y que llega al país bajo la dirección de Pablo Halpern. Este trabajo se presenta desde este viernes en el Teatro Zoco de Lo Barnechea. Conduce Cecilia Rovaretti y Sebastián Esnaola.

Johann Wald interviews the young Aragonese artist Anaju, known for having taken part in OT, who has just released her debut album, Rayo.

Episode 195: Nacho Monclus is a true Spaniard steeped in its' history and culture. He's bringing one of the most dynamic Spanish Portfolios to the U.S.

From studying the obscure Aragonese language, to being a plumber, to winning wine competitions. Nacho Monclus's life has been a winding road filled with tragedy, triumph and lots of hilarious moments. Check out the website: www.drinkingonthejob.com for great past episodes. Everyone from Iron Chefs, winemakers, journalist and more.

Ep 455: Cava (Update) and the Other Quality Sparkling Wines of Spain

Much has changed since our original 2017 episode (199) on Cava and Spanish sparkling wine. It's time for a refresh and an update! Photo: Cava cork. Credit: cava.wine In this episode we fill you in on the roller coaster the DO has been on since 2017 and where it stands today. The story shows how Spain has moved from just being ON the radar of international wine buyers to moving to a level of sophistication that demands its regions have the kind of terroir focus of the other great wine nations of the Old World – France, Italy, Germany, and Austria, to name a few. We review the regulations, changes, and the strife in the region and discuss what to seek out to get the best of these highly accessible, delicious, and decidedly Spanish wines. Here are the show notes... The Basics We start with the statistics on Cava -- it encompasses 38,133 ha/94,229 acres and made 253 MM bottles in 2021 91% of Cava is white, 9% is rosado (rosé) Various zones produce the wine, but Penedés is the heart of Cava production, with more than 95% of total output We discuss the early history of the area, beginning with the first sparkling production in 1872 with Josep Raventós to the point where the DO is formed in 1991 – we leave the modern history until later, as complex and muddled as it is! Map: The overly spread out regions of Cava. Credit: Cava DO We then get into the grapes and winemaking: Whites: Since most Cava is white, the white grapes dominate. Most important are the indigenous grapes, Macabeo (Viura, the white of Rioja), Xarel-lo, and Parellada. Chardonnay is also authorized, as well as Subirat Parent (Malvasia) for semi-sweet and sweet Cava. Photo: Macabeo. Credit: D.O. Cava Reds: Used for rosado (rosé), native grapes are Garnacha (Grenache), Trepat, and Monastrell (Mourvèdre). The Cava DO authorized Pinot Noir for use in rosado in 1998 Winemaking: We discuss the vineyard requirements for the making of quality Cava, including the importance of gentle picking and transport to the winery to prevent oxidation We briefly review the Traditional Method (Champagne Method) of winemaking, which is how all Cava is made Photo: Riddled Cava, ready for disgorgement.. Credit: D.O. Cava We discuss the aging qualifications for Cava, Cava Reserva, Cava Gran Reserva, and Cava Paraje Calificada that range from a minimum nine months to several years, and what each style yields We review the various dosage levels so you know what to look for: “Brut Nature” - no added sugar Cava Extra Brut – very little sugar Cava Brut: Slightly more added sugar in the dosage, sugar is barely noticeable Cava Extra Seco: heavier mouthfeel, noticeable sugar Cava Seco: Dessert level, very sweet Semi Seco: Even sweeter Dulce – Super sweet We discuss why Cava is such a big mess, with much infighting in its modern history, and why not all sparkling Spanish wine is created the same: We talk about the first fissures in Cava, with the 2012 break off of Cava OG producer Raventós i Blanc leaving the Cava DO because the quality standards were too low -Vino de la tierra Conca de l'Anoia (their own site) Photo: Raventós i Blanc Rosado, Vino de la Tierra We discuss the 2015 formation of The Association of Wine Producers and Growers Corpinnat (AVEC) or Corpinnat. We define the group and talk about its requirements for the small member producers: Mission: Create a distinguished, excellent quality, terroir-driven sparkling wine based solely on Penedès, rather than far flung regions that make lesser wine. To raise the profile of Cava from cheap shit to good stuff Photo: Corpinnat corks. Credit: Corpinnat Website Corpinnat Requirements At least 75% of the grapes must be from vineyards owned by the winery, wine must be made on the premises of the winery Minimum price paid for livable wages to the growers Certified organic and hand harvested grapes 90% of the grapes must be indigenous varieties: Macabeo, Xarel-lo, Parellada for whites, Garnacha, Trepat, Monastrell, for reds. 18 months minimum aging **By design: Cava's three biggest producers can't meet the requirements: Cordoniu, Freixenet and García Carrión – which is why Corpinnat started in the first place, to raise the quality standard and allow smaller producers a voice Corpinnat members (2022): Gramona, Llopart, Recaredo, Sabaté i Coca, Nadal, Torelló, Can Feixas, Júlia Bernet, Mas Candi, Can Descregut, Pardas We discuss the qualifications of the Cava Paraje Calificado classification, created by the Cava DO in 2017 for single-estate sparkling wines with a vineyard designation, lower yield, and a longer aging period Cava de Paraje Calificado requirements include specifications for: lower yield, manual harvest, minimum fermentation time in the bottle at 36 months. Vines must be at least 10 years old and the wine must be produced locally in the same winery that grows the grapes. Issues: Includes the large wineries' estate vineyards and (originally) some smaller ones but doesn't address the issue of quality or cohesive terroir/flavor. It's like a medal system – here are our best wines! Photo: Paraje Califado Cava -- Can Sala, Freixenet Disastrous conclusion: The Cava Paraje Calificada was the solution to the Corpinnat – it was meant to be more inclusive. But Corpinnat was supposed to be a new small producer/ quality designation within Cava. Because it excludes large producers, the DO wouldn't allow Cava and Corpinnat on the same label, and Corpinnat left the DO. They cannot use Cava, or Gran Reserva on their labels. Of the 12 wines approved as CPC in 2017, 5 aren't CPC anymore, only Corpinnat We address most recent regulations of Cava in 2020 The Cava Regulatory Council approved new zoning of the Cava DO. We review the subzones that are supposed to create a better delimitation for consumers: Comtats de Barcelona - 95%+ of Cava production Includes Sant Sadurní d'Anoia, the "capital of Cava" – where the first bottles of Cava were produced in 1872 Location: In Catalonia, in northeast Spain. Along the Mediterranean coast near Barcelona Climate: Mediterranean climate, slight variations inland versus coast but mostly long summer, lots of sun, hot summer and spring - easy to ripen grapes, lots of different grapes thrive Land: Diverse terrain – various exposures, orientation, altitudes, and microclimates Five Sub-zones (used for Reserva and Gran Reserva Cava, more limited yields, organic viticulture, vineyards 10+ years old): Valls d'Anoia Foix, Serra de Mar, Conca del Gaià, Serra de Prades and Pla de Ponent Each has a slightly different character – some more at elevation, some farther from the sea – slight variations in flavors and what grows where Map: Detail of the Comtats de Barcelona Cava Zone. Credit: Cava DO The Ebro Valley area Northernmost part of the DO, far in the interior, near and influenced by the river Ebro Climate: Temperate, continental climate – summers are hot and dry with cold winters Two subzones (used for Reserva and Gran Reserva Cava, more limited yields, organic viticulture, vineyards 10+ years old): the Alto Ebro around Rioja, Navarra, and the Basque area of Álava and the Cierzo Valley Sub Zone. The Cierzo is near the Aragonese city of Zaragoza in the central area of the Ebro River, with strong regional winds (the Cierzo) to dry out the area Map: Detail of the Ebro River Valley Cava Zone. Credit: Cava DO Smaller zones: Levante: (Eastern Highlands, no official name yet), in interior of Valencia province, with a dry Mediterranean to semi continental climate depending on whether altitude) Viñedos de Almendralejo (Almendralejo vineyards): Fairly flat, southwestern-most part of the DO. A very dry, hot climate, with warm wind, known as the solano We end with an update of where Cava is today (hint: it's huge and growing, it's trying to improve by moving towards organics, it's still fighting against Corpinnat) and what could be the next step for Corpinnat too. A fascinating show that takes you on the wild ride that the region and wine has been on since we first discussed it those many years ago. __________________________________________________ Thanks to our sponsors this week: Wine Spies uncovers incredible wines at unreal prices - on every type of wine in a variety of price points. It's not a club and there's no obligation to buy. Sign up for their daily email and buy what you want, when you want it. They have a build-a-case option, so you can mix and match wines while enjoying free shipping on every purchase. Visit www.winespies.com/normal you'll get $20 credit to use on your first order! Check them out today! If you think our podcast is worth the price of a bottle or two of wine a year, please become a member of Patreon... you'll get even more great content, live interactions and classes! www.patreon.com/winefornormalpeople To register for an AWESOME, LIVE WFNP class with Elizabeth go to: www.winefornormalpeople.com/classes Sources: www.cava.wine https://www.raventos.com https://www.corpinnat.com https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2019/02/nine-producers-break-with-cava-to-form-corpinnat/ https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/new-breakaway-sparkling-wine-appellation-to-rival-cava-20501/

35 - Nessuno si aspetta l'inquisizione aragonese - "Nicolas Eymerich, inquisitore" di V. Evangelisti

In questa puntata vi andremo a parlare di "Nicolas Eymerich, inquisitore", primo libro della famosa serie creata da Valerio Evangelisti che pone come protagonista l'inquisitore spagnolo Nicolas Eymerich vissuto a ridosso del 1300, alternando la narrazione con diversi piani temporali differenti ed elementi fantascientifici e fantastici. https://www.instagram.com/bla.blafantasy/ Pagina Facebook https://www.facebook.com/blablafantasy/ Youtube: https://youtu.be/btiiR1HJY_c Un ringraziamento a Riccardo per la traccia musicale in sottofondo https://campsite.bio/spinaaqm https://www.fiverr.com/riccardos17?source=gig_cards&referrer_gig_slug=do-an-amazing-and-chill-lo-fi-soundtrack-for-your-video&ref_ctx_id=6ed784fb0bae92f95938a321774d6e9d --- Send in a voice message: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/blablafantasy/message

138 - Aragonese Sardinia and Sicily (1410 - 1500)

We take a quick look at some of the situations and key events in Sardinia and Sicily in the 15th century as the Aragonese consolidate their hold over their new possessions

133 – catching up with Genoa… again (1310 – 1442)

and 15th century Genoa to catch up on all their wars with Venice and the Aragonese as well as all the internal infighting between the various Doria, Spinola, Fieschi, Grimaldi and Campofregaso for which external rulers are constantly called in, the, Anjou, Milan, France, Monferrato, milan again and so on.

133 – catching up with Genoa… again (1310 – 1442)

and 15th century Genoa to catch up on all their wars with Venice and the Aragonese as well as all the internal infighting between the various Doria, Spinola, Fieschi, Grimaldi and Campofregaso for which external rulers are constantly called in, the, Anjou, Milan, France, Monferrato, milan again and so on.

WIKIRADIO - La distruzione dell'archivio angioino-aragonese a San Paolo Belsito

Il 30 settembre 1943 le truppe naziste appiccano il fuoco all'archivio angioino-aragonese a San Paolo Belsito in provincia di Napoli, con Isabella Insolvibile

Alfonso I “the Battler” of Aragon: Hero, Villain, or Both? Dr. Kyle C. Lincoln

Alfonso I “the Battler” of Aragon: Hero, Villain, or Both? This episode explores a series known as "Heroes or Villains in Medieval Iberia where the audience decides if a certain historical character is a hero, a villain or if it is more complicated than one over the other. Alfonso was the son of Sancho V Ramírez. He was persuaded by Alfonso VI of Leon and Castile to marry the latter's heiress, Urraca, widow of Raymond of Burgundy. In consequence, when Alfonso VI died (1109) the four Christian kingdoms were nominally united and Alfonso I took his father-in-law's imperial title. The union failed, however, because Leon and Castile felt hostility toward an Aragonese emperor; because Urraca disliked her second husband; and because Bernard, the French Cluniac archbishop of Toledo, wanted to see his protégé, Alfonso Ramírez (infant son of Urraca and her Burgundian first husband), on the imperial throne. At Bernard's prompting, the Pope declared the Aragonese marriage void, but Alfonso continued to be involved in civil strife in the central kingdom until he eventually gave up his claims in favour of his stepson after the death of Urraca (1126). Despite these embroilments, he achieved spectacular victories against the Moors, capturing Saragossa in 1118 and leading a spectacular military raid far into southern Andalusia in 1125. In his campaigns he received much help from the rulers of the counties north of the Pyrenees, resulting in the involvement of Aragon in the affairs of southern France. Alfonso was fatally wounded in battle at Fraga in 1134. Deeply religious, he bequeathed his kingdom to the Templars and the Hospitallers, but his former subjects refused to accept the donation, and the kingdoms eventually came under the control of the counts of Barcelona. Description above was taken from Britannica. And so at the end we look at his achievements, his shortcomings and we put him on a scale to see who he really was and how he is viewed today. For more information on Dr. Lincoln and his awesome work check out these links below to his book and other writings! KING ALFONSO VIII OF CASTILE : GOVERNMENT, FAMILY, AND WAR Edited by Miguel Gómez, Kyle C. Lincoln and Damian J. Smith https://www.fordhampress.com/9780823284146/king-alfonso-viii-of-castile/ Academia Profile: https://norwich.academia.edu/KyleLincoln --- Support this podcast: https://anchor.fm/antiquity-middlages/support

History of the Mongols SPECIAL: Rabban Bar Sauma

“There was a certain man who was a believer, and he was a nobleman and a fearer of God. He was rich in the things of this world, and he was well endowed with the qualities of nature; he belonged to a famous family and a well-known tribe. His name was SHIBAN the Sa'ora. He dwelt in the city which is called [...] KHAN BALIK , [...] the royal city in the country of the East. He married according to the law a woman whose name was KEYAMTA. And when they had lived together for a long time, and they had no heir, they prayed to God continually and besought Him with frequent supplications not to deprive them of a son who would continue [their] race. And He who giveth comfort in His gracious mercy received their petition, and He showed them compassion. For it is His wont to receive the entreaty of those who are broken of heart, and-to hearken unto the groaning of those who make supplications and petitions [to Him]. [....] Now God made the spirit of conception to breathe upon the woman Keyamta, and she brought forth a son, and they called his name " SAWMA.” And they rejoiced [with] a great joy, neighbours of his family and his relations rejoiced at his birth.’ So begins the history of Rabban bar Sauma, as translated by E. Wallis Budge. There were a number of travellers, missionaries, diplomats and merchants who made journey from Europe to China during the height of the Mongol Empire. While Marco Polo is the most famous of these, we have also covered a few other travellers in previous episodes. Yet, there were also those who made the harrowing journey from China to the west. Of these, none are more famous than Rabban bar Sauma, the first known individual born in China who made the journey to Europe. Rabban bar Sauma was a Turkic Christian monk who travelled from Khanbaliq, modern-day Beijing, across Central Asia, the Ilkhanate, the Byzantine Empire, Italy, all the way to the western edge of France, visiting Khans, Emperors, Kings and Popes. Our episode today will introduce you to Rabban Sauma and his incredible journey across late 13th century Mongol Eurasia. I’m your host David, and this is Kings and Generals: Ages of Conquest. Sauma was born around 1225 in the city of Yenching, on which Beijing now sits. Yenching of course, we have visited before, when it was known as Zhongdu, the capital of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty. The Mongols took the city after a bloody siege in 1215, which we covered back in episode 7 of this season. Sauma was born to Turkic parents, either Onggud or Uighur, two groups which had long since recognized the supremacy of Chinggis Khan. Sauma’s parents were Christians of the Church of the East, often called, rather disparagingly, Nestorians. Nestorius was a 5th century archbishop of Constantinople who had argued, among other things, the distinction between Christ’s humanity and his divinity, and that Mary was mother of Jesus the man, but not of Jesus the God. For if God had always existed, then he could not have had a mother. For this Nestorius was excommunicated at the Council of Ephesus in 431 and his followers scattered across the east. From the Sassanid Empire they spread across Central Asia, reaching China during the Tang Dynasty. By the 12th century, the adaptable Nestorian priests converted several of the tribes of Mongolia, from the Naiman, the Kereyit to the Onggud, to which Sauma likely belonged. These Eastern Christian priests stayed influential among the Mongols for the remainder of the 13th century, with a number of prominent Mongols adhering to their faith. Sorqaqtani Beki, the mother of Great Khans Mongke and Khubilai, was perhaps the best known of these. The young Sauma took his Christian faith seriously; so seriously, his parents sought to dissuade him, fretting the end of their family line if their son became a monk. Refusing fine meats and alcohol, Sauma instead hungered for ecclestical knowledge and purity. Accepted into the Nestorian clergy of Yenching in 1248, at age 25 he donned the tonsure and garb of the monk. Developing a reputation for asceticism beyond even his fellow monks, he largely secluded himself in his own cell for 7 years before leaving the monastery for the mountains. His devotion to Christ made him famous among the Nestorians of North China and Mongolia, attracting the attention of a young Onggud Turk named Markos. From the Onggud capital of Koshang in modern Inner Mongolia, Markos was mesmerized by the stories of the holiness of Sauma. The 15 year old Markos marched by himself to Sauma in 1260. Impressed by the youth’s tenacity even as he attempted to dissuade him from joining the monastery, Sauma eventually took Markos under his wing. Markos proved himself an excellent student, and within three years was accepted into the Nestorian monastic life. Sauma and Markos became fast friends and pillars of the Nestorian community around Yenching, which by then was the capital of the new Great Khan, Khubilai, and renamed to Dadu, “Great City,” or Khanbaliq, “The Khan’s City,” to Turkic and Mongolian speakers. Khanbaliq is the origins of Marco Polo’s somewhat distorted version of Cambulac. While Sauma was happy to spend his life in the mountains near Dadu, Markos was much more energetic, and sought to convince his friend to partake in the most difficult of journeys; to the holy city of Jerusalem to be absolved of their sins. Sauma tried to scare Markos off this goal, and it was not until around 1275 that Sauma was convinced to accompany his friend. They went to Khanbaliq for an escort and supplies, and here news of their mission came to the most powerful monarch on the planet, Khuiblai Khan. Several sources, such as the Syriac Catholicos Bar Hebraeus, attest that Sauma and Markos were sent west by Kublai to worship in Jerusalem or baptize clothes in the River Jordan. Such a task is similar to the orders Kublai gave to Marco Polo’s father and uncle, instructed to bring back Catholic priests and sacred oil from Jerusalem for Yuan China. Khubilai often tried to appear a friend to all religions within his realm, and may have felt the need to honour his own mother’s memory, as she had been a Christian. That Sauma and Markos went with the blessings of the Great Khan holding his passport (paiza) would explain the favoured treatment they received over their voyage. Interestingly though, the main source for Bar Sauma’s journey, a Syriac language manuscript compiled shortly after his death from notes and an account he had made in his life, makes no mention of Khubilai’s involvment. Historian Pier Giorgio Borbone suggests it was deliberately left out, instead playing of the religious aspect of the pilgrimage as emerging from Markos and Sauma themselves, rather than imply they only made the journey on the order of Khubilai. Setting out around 1275, Sauma, Markos and an escort began their journey to the west. Through the Yuan Empire they were met by ecstatic crowds of Nestorians coming out to see the holymen, showering them with gifts and supplies. Two Onggud nobles, sons-in-laws to the Great Khan, provided more animals and guides for them, though they warned of the dangers now that the Mongol Khanates were at war. They followed one of the primary routes of the Silk Road, via the former territory of the Tangut Kingdom, the Gansu Corridor, to the Tarim Basin, cutting south along the desolate Taklamakan desert, the harshest stretch of their journey. After staying in Khotan, they moved onto Kashgar, shocked to find it recently depopulated and plundered, a victim of Qaidu Khan. Passing through the Tien Shan mountains to Talas, they found the encampment of that same Khan. Here they minimized any connections they had to Khubilai, instead portraying themselves on a mission of personal religious conviction and prayed for the life of Qaidu and his well being, asking that he provid supplies to assist in their journey. Qaidu let them through, and Sauma and Markos continued on a seemingly uneventful, but strenuous trip through Qaidu’s realm, the Chagatai Khanate and into the Ilkhanate. Sauma and Markos’ journey to Jerusalem halted in Maragha, chief city of the Ilkhanate. There, the head of the Nestorian Church, Patriarch Mar Denha, found use for these well-spoken travellers affiliated with the Khan of Khans. Mar Denha had not made himself many friends within the Ilkhanate, in part for his hand in the violent murder of a Nestorian who had converted to Islam. As a result the Il-Khan, Hulegu’s son Abaqa, had not provided letters patent to confirm Denha in his position, wary of alienating the Muslims of his kingdom. Mar Denha believed monks sent from Abaqa’s uncle Khubilai would be most persuasive. Abaqa Il-Khan treated Sauma and Markos generously, and perhaps influenced by his Christian Byzantine wife, on their urging he agreed to send Mar Denha his confirmation. In exchange, Mar Denha was to provide an escort for Sauma and Markos to reach Jerusalem, but the roads were closed due to war between the Ilkhanate and the Mamluk Sultanate. When Markos and Sauma returned to Mar Denha, he told them visiting his own Patriarchate was just as good as visiting Jerusalem, and gave them new titles. Both were made Rabban, the Syriac form of Rabbi. Markos was made Metropolitan of the Nestorians of Eastern Asia, essentially a bishop, and given a new name: Yabhallaha, by which he is more often known, while Rabban bar Sauma became his Visitor-General. Suddenly promoted but unable to return east due to a breakout of war between the Central Asian Khanates, Rabban Sauma and Mar Yabhallaha stayed in a monastery near Arbil until the sudden death of Mar Denha in 1281. His experience with the Mongols and knowledge of their language made Yabhallaha a prime candidate to succeed Mar Denha, and the other Metropolitans anointed him Patriarch of the Nestorians. Wisely, Rabban Sauma encouraged Yabhallaha to immediately seek confirmation from Abaqa Il-Khan, who appreciated the move and rewarded Yabhallaha and the Nestorians of the Ilkhanate with gifts, such as a throne and parasol, as well as tax privileges. Abaqa soon died in 1282, and Yabhallaha and Sauma faced scrutiny under Abaqa’s successor, his Muslim brother Teguder Ahmad. Accusations were made that the Nestorians were defaming Teguder Il-Khan in letters to Khubilai. Placed on trial before the Il-Khan, the two friends fought for their innocence and outlasted him. In 1284 Teguder was ousted and killed by Abaqa’s son Arghun. Mar Yabhallaha immediately paid homage to Arghun, in him finding a firm supporter. With Arghun’s backing, Yabhallaha removed his enemies from within the Nestorian church and strengthened his power. Desiring to complete the war with the Mamluk Sultanate, under Arghun efforts to organize an alliance with Christian Europe against the Mamluks reached new heights. Since the days of Arghun’s grandfather Hulegu, the Il-Khans had sent envoys to Europe in an effort to organize a Crusader-Mongolian alliance against the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt. Despite some close attempts, there had not yet been successful cooperation. Arghun was determined to change this and organize the coalition which would finally overcome the Mamluks. Desiring the most effective envoy possible, Arghun turned to Mar Yabhallaha to suggest an influential, well travelled and respectable Christian to send to spur Crusading fervour, aided by promises that Arghun would restore Jerusalem to Christian hands. Yabhallaha had just the man. Turning to his longtime friend, Yabhallaha asked Rabban bar Sauma to carry the Il-Khan’s messages westwards. Provided letters for the Kings and Popes, as well as paizas, gold, animals and provisions, in the first days of 1287, after a tearful goodbye with Mar Yabhallaha, the 62 year old Rabban Sauma set out, accompanied by at least two interpreters from Italy in his escort. The first steps of his route are unclear, likely taking the caravan routes from northern Iraq to somewhere along the southeastern Black Sea coast. From there they took a ship to Constantinople and met the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II. As recorded in the Syriac history of Rabban Sauma, quote: “And after [some] days he arrived at the great city of CONSTANTINOPLE, and before they went into it he sent two young men to the Royal gate to make known there that an ambassador of [Khan] Arghon had come. Then the [Emperor] commanded certain people to go forth to meet them, and to bring them in with pomp and honour. And when RABBAN SAWMA went intothe city, the [Emperor] allotted to him a house, that is to say, a mansion in which to dwell. And after RABBAN SAWMA had rested himself, he went to visit the [Emperor, Andronikos II] and after he had saluted him, the [Emperor] asked him, "How art thou after the workings of the sea and the fatigue of the road?" And RABBAN SAWMA replied, "With the sight of the Christian king fatigue hath vanished and exhaustion hath departed, for I was exceedingly anxious to see your kingdom, the which may our Lord establish!" Emperor Andronikos II politely welcomed the embassy, dining them and providing a house for their stay. Giving the gifts and letters from Arghun, Rabban Sauma met his first frustration as efforts to broach military aid led nowhere. The Emperor Andronikos provided gifts, excuses, and promised exactly no military aid for the Il-Khan. Whatever disappointment Rabban Sauma felt was offset with a tour of the sites of Constantinople, especially the great church of Hagia Sophia. In his homeland churches were small buildings or even mobiles tents; in Ani, in Armenia, he saw a city famous for its many churches. But nothing could compare to the majesty of the Hagia Sophia, the quality and colour of its marble, its 360 columns, the great space and seemingly floating roof. The mosaics, the shrines and relics alleged to date to the earliest days of Christianity, all captured Sauma’s heart. Of the church’s famous dome, Sauma wrote: “As for the dome of the altar it is impossible for a man to describe it [adequately] to one who hath not seen it, and to say how high and how spacious it is.” In his often laconic account of his travels, it is these icons of Christianity which earn the greatest description, and stood out to him more than his usually unsuccessful diplomatic efforts. Departing Constantinople, by sea he set out for Rome. The voyage was rough, and on 18th June 1287 he was greeted by a terrifying spectacle, the eruption of Mt. Etna where fire and smoke ascended day and night. Passing Sicily he landed at Naples, where he was graciously welcomed by Charles Martel, the son of the Napolese King Charles II, then imprisoned in Aragon. From the roof of the mansion Sauma stayed at, on June 24th he watched Charles’ forces be defeated by the Aragonese fleet in the Bay of Sorrento. Sauma remarked with surprise that the Aragonese forces, unlike the Mongols, did not attack the noncombatants they came across. European chroniclers attest that later in June, after Sauma had moved onto Rome, the Aragonese began ravaging the countryside anyways. In Rome later in 1287, Sauma’s hopes to meet the Pope were dashed as Pope Honourius IV had died in April that year. Finding the Cardinals in the midst of a long conclave to choose his successor, Sauma was welcomed before them as the envoy of the Il-Khan. Unwilling to commit to any alliance without a Pope, the Cardinals instead asked where Sauma came from, who the Patriarch of the East was and where he was located. Avoiding Sauma’s attempts to get back to his diplomatic purpose, the Cardinals then shifted to theological matters, grilling Sauma on his beliefs. The Nestorian impressed them with his knowledge of the early church, and managed to deftly slide past the disputes which had caused the excommunication of Nestorius some 860 years prior. Finding no progress on the diplomatic mission, Sauma engaged in a more personal interest, exploring the ancient relics and monuments to Christendom. The account of Sauma’s journey indicates he visited “all the churches and monasteries that were in Great Rome.” At times, he misunderstood the strange customs of the locals, believing the Pope enthroned the Holy Roman Emperor by using his own feet to lift the crown onto his head. With no progress to be made in Rome until the new Pope was elected, Sauma searched for Kings of the Franks most known for Crusading. After a brief tour of Tuscany, by the end of September 1287 Sauma was in Paris, there greeted with a lavish reception by King Phillip IV, who hosted a feast for this illustrious envoy. In Rabban Sauma’s account, he wrote” “And the king of France assigned to Rabban Sawma a place wherein to dwell, and three days later sent one of his Amirs to him and summoned him to his presence. And when he had come the king stood up before him and paid him honour, and said unto him, "Why hast thou come? And who sent thee?" And RABBAN SAWMA said unto him, "[Khan] ARGHON and the Catholicus of the East have sent me concerning the matter of JERUSALEM." And he showed him all the matters which he knew, and he gave him the letters which he had with him, and the gifts, that is to say, presents which he had brought. And the king of FRANCE answered him, saying, "If it be indeed so that the MONGOLS, though they are not Christians, are going to fight against the Arabs for the capture of JERUSALEM, it is meet especially for us that we should fight [with them], and if our Lord willeth, go forth in full strength.” Moved by the willingness of the Mongols to restore Jerusalem to Christian hands, Phillip promised to send a nobleman alongside Rabban Sauma to bring his answer to Arghun. With at least one king seemingly onboard, Sauma spent the next month touring Paris, visiting churches and impressed by the great volume of students within the city. Phillip showed Sauma the private relics of the French Kings, including what Phillip claimed was the Crown of Thorns, sold to his grandfather by the Emperor of Constantinople in 1238. Around mid-October 1287, Rabban Sauma had moved across France to Gascony, where the King of England Edward I, old Longhsanks himself, was staying at Bordeaux. Edward was known to the Mongols, having gone on an inconclusive Crusade to Syria in 1271. Abaqa Il-Khan had attempted to coordinate movements with Edward during his campaign, but neither side had been able to line up their forces. Edward, then just the crown prince of England, had succeeded in doing little more than carry out small raids, assist in organizing a treaty between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and Mamuk Sultan Baybars. and survive an assassination attempt. Abaqa had sent envoys in 1277 apologizing to Edward for being able to provide sufficient aid and asked for him to return, but to no avail. Edward, by then the King of England, was by then rather more concerned with France and the conquest of Wales. Ten years in early 1287, Edward had promised to take up the Cross again, and was excited by the arrival of Rabban Sauma late that year. Promising assistance, he invited Rabban Sauma to partake in the Eucharist with him, gave him leave to visit the local churches, and provided gifts and assistance when Sauma went back on the road to Rome. Feeling himself successful, by the time he returned to Rome in early 1288 a new Pope had been elected, Nicholas IV. The first Pope from the Franciscan Order, Nicholas was a man keenly interested in missionary efforts and the restoration of the Holy Land to Christian hands. It was under his aegis that John de Monte Corvino would travel to Dadu to establish a Catholic archbishopric there. Having interacted with each other during Sauma’s first visit to the Cardinals, Sauma and the new Pope got on splendidly. Kissing the hands and feet of Pope Nicholas, Sauma was provided a mansion for his stay in Rome and invited to partake in the feasts and festivities around Easter. Sauma on occasion led in the Eucharist beside the Pope, drawing crowds from across Rome eager to see how this foreign Christian undertook Mass. Though the language differed, the crowds were ecstatic that the rites themselves seemed the same. Despite their friendship, no promises of organizing a crusade against the Mamluks were forthcoming. The Pope lacked the influence to send a large body of armed men on yet another disatrous journey. The crusades of the 13th century to the Holy Land had been catastrophes. The most thoroughly organized crusades of the century were those organized by King Louis IX of France. The first had ended in his capture by the Mamluks in Egypt in 1250, while the second had resulted in his death outside of Tunis in 1270. If even this saintly, highly prepared king had been met with failures, then what chance would any other force have? Nicholas wanted to convert Muslims and retake Jersualem, yes, but was very aware of the practicalities involved by this point. And so, Rabban Sauma decided to return to the Ilkhanate. Nicholas asked Sauma to stay in Rome with him, but Sauma insisted he was only there as a diplomat, and it was his duty to return east. The Nestorian did convince the Head of the Catholic Church to give him, somewhat reluctantly, holy relics: a piece of Jesus’ cape, the kerchief of the Virgin Mary, and fragments from the bodies of several saints. Along with those were several letters for the Il-Khan, Mar Yabhallaha and Rabban Sauma. Copies of these letters survive in the Vatican archives, and though the letter to Yabhallaha confirms him as head of the Christians of the East, it is surprisingly condescending, explaining basic tenets of Christianity. Embracing Rabban Sauma one final time, he was dismissed and by ship, returned to the Ilkhanate. On his return, he was warmly welcomed by his longtime friend Mar Yabhallaha and the Il-Khan Arghun. Arghun hosted a feast for them, personally serving them and richly rewarding the old man for his great efforts. Yet his efforts came to naught. The Pope had provided no assurances, and despite continued correspondence neither Phillip nor Edward committed men to the Holy Land, too preoccupied with their own conflicts. Arghun sent an embassy in 1289 telling the two monarchs that he would march on Damascus in January 1291 and meet them there. Distracted by turmoil on his borders, Arghun instead died of illness in March 1291. Acre, the final major Crusader stronghold, was taken by the Mamluks two months later, ending the Crusader Kingdoms and the possibilities of European-Mongol cooperation. Despite some outrage in connected circles in Europe, the fall of Acre merited no revival of any Crusader spirit for the region. Rabban Sauma largely retired to his own church for his last years, but along with Mar Yabhallaha continued to visit the court of the Il-Khans, particularly Geikhatu who continued to patronize minority religions of the Ilkhanate. Perhaps in 1293 they met another international traveller; Marco Polo, who spent much of that year in the Ilkhanate during his return from China. We have no way of confirming this, though we can imagine Geikhatu Il-Khan introducing two men who had both travelled across the continent, humoured by the individuals brought together by Mongol rule. Polo had arrived in China around the same time that Rabban Sauma and Markos had begun their own western journey. As Marco had spent much of his time in China in Bar Sauma’s city of birth, perhaps Polo told him of the things he had missed in the last twenty years, what had changed in Dadu and what had stayed the same, stirring memories in Rabban Sauma of land and family that he never saw again. Rabban Sauma died in January 1294, leaving his friend Mar Yabhallaha alone in an Ilkhanate that, after the death of Geikhatu and conversion of the Ilkhans to Islam, grew increasingly mistrustful and hostile to non-Muslims. By the time of Mar Yabhallaha’s death in 1317, the brief flourishing of the Nestorian church under Ilkhanid patronage was over, and their influence across Central Asia dissipated with the continued conversion of Mongols across the region. The journey of Rabban Sauma was forgotten. His persian diary on his voyages was translated into Syriac not long after his death but was lost until its rediscovery in the 19th century. Translated now into several languages, Sauma’s journey shines another light on the integration of East and West under the Mongols, when for the first time a Christian Turk from China could travel to the Pope and Kings of Europe. Our series on the Mongol Empire in the late thirteenth century and fourteenth century will continue, so be sure to subscribe to our podcast. If you’d like to help us keep bringing you great content, please consider supporting us on patreon at www.patreon.com/kingsandgenerals, or consider leaving us a review on the podcast catcher of your choice, or sharing this with your friends. All your efforts help immensely. This episode was researched and written by our series historian, Jack Wilson. I’m your host David, and we’ll catch you on the next one.

LE MERAVIGLIE Fortezza Aragonese di Le Castella raccontata da Vito Bianchi

La Fortezza Aragonese di Le Castella è un'imperiosa struttura in mezzo al mare, collegata alla terra da un sottilissimo istmo. Lo storico Vito Bianchi ci descrive questo luogo in un caleidoscopio dove si incontrano l'antico popolo dei Bruz...

In this episode of Wine and Dime we welcome back our very own Rooted Planning Group Financial Planner Kerrie Beene. Kerrie is back to help us continue the theme of January of “Getting Organized”. Kerrie is a bit of an expert on spending plans, so, she is the perfect guest to have on this weeks episode. She shares her insights on her own spending plans, and what it takes to build one for your family. Don't forget to rate and subscribe and thank you for listening!! KERRIE BEENE - CFP®FINANCIAL PLANNERA little bit about Kerrie Beene, CFP®… My own personal financial journey has taught me that while they're important, life is more than numbers. Finding joy in the journey towards personal goals is key. A smart plan with a lot of heart goes a long way to keeping daily financial decisions in line with your long term goals. I graduated from Southeastern Oklahoma State University with a degree in Business Administration and hold a certificate in Financial Planning from Wake Forest University. I began my career in financial planning by starting my own company, Beene Financial Planning. Having the desire to work as a team, I then joined Irvine Wealth Planning Strategies. My roots in Southeast Oklahoma have given me great insight on the need for financial planning that is not just investment focused, but also focused on all the other financial planning decisions. I enjoy, and work best, with those who are ready to take control of their finances and use their money to fulfill their goals and dreams. In November of 2016 I sat for the CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ designation, and in May of 2019 successfully completed my experience requirements. I am now the Director of Educational Services for Rooted Planning Group. What does that mean? In addition to working as a co-planner, I also focus on: College Pre-Planning: Late stage (Freshman - Senior) college planning, seeking scholarships, estimating expected family contribution, assistance with FAFSA and asset utilization. Funding of education vehicles (i.e. 529 plans) and utilization recommendations. We have set the price for this service at $1,000. College Graduate Planning: This is for the new graduate. We sit down with them to discuss budgeting, how to negotiate salary, understand employee benefits and education benefits, review of student loans and other debt, savings opportunities and large purchase planning. We have set the price for this service at $299. We also want to continue developing the employer education services, as well as getting financial education into the schools. Grenache (Garnacha) WineGrenache (Garnacha) is a red-wine grape grown extensively in France, Spain, Australia and the United States. It is particularly versatile both in the vineyard and the winery, which may explain why it is one of the most widely distributed grapes in the world. Grenache is the French (and most internationally recognized) name for the grape, but it has a number of synonyms. In Spain, where it is one of the country's flagship varieties, it is known as Garnacha, and on the island of Sardinia it has been known for centuries as Cannonau. Some believe that the grape originated in Sardinia, and was taken back to Spain by the Aragonese, who occupied the island in the 14th Century. Gnarly old Barossa Grenache vines ©Turkey Flat Vineyards In France, Grenache is most widely planted in the southern Rhone Valley and throughout both Provence and Languedoc-Roussillon. It is most commonly found alongside Syrah and Mourvedre in the classic Southern Rhone Blend (notably in Cotes du Rhone wines), and is the main grape variety in Chateauneuf-du-Pape. Grenache's versatility provides winemakers with all sorts of possibilities. Grenache-based rosé is one of southern France's signature wine styles. The variety is common...

104 – The last Sardinian Judicate (1323-1326)

After a quick recap of what was going on around Italy in 1323, we get to the Aragonese invasion of Sardinia that put a definitive end to the presence of the Republic of Pisa on the island leaving the Judicate of Arborea as the last of the old four Judicates surrounded by the new "Kingdom of Sardinia"

104 – The last Sardinian Judicate (1323-1326)

After a quick recap of what was going on around Italy in 1323, we get to the Aragonese invasion of Sardinia that put a definitive end to the presence of the Republic of Pisa on the island leaving the Judicate of Arborea as the last of the old four Judicates surrounded by the new "Kingdom of Sardinia"

Odds On: La Liga Matchday 12 - Football Match Tips, Bets, Odds & Predictions

This is an audio version of our YouTube video. We begin our Liga preview on Friday night as mid-table Athletic Bibao welcome relegation-threatened Celta Vigo to the San Mames. The Basque Country side have been up and down for the past few weeks, winning two, losing two and drawing one of their previous five games. Celta ended a run of eight games without a win last weekend. On Saturday, another side battling for survival are in action. 19th placed Levante, with one win to their name, play Getafe. Then, at 3.15pm (UK), we've got a superb game to bring you. Sevilla vs Real Madrid at the Ramon Sanchez-Pizjuan! Josep Lopetegui's men have just come suffered a humiliating 4-0 defeat to Chelsea in the Champions League, whilst Real Madrid aren't fairing much better in European competition. Later that day, two of La Liga's other big clubs are in action. Atletico Madrid – second in the table – play Real Valladolid, and Barcelona – not having a good time of it – go to surprise package Cadiz. Ronald Koeman's side have breezed through their Champions League qualification with five wins and a 100% record. They have more wins in Europe than La Liga this year. Into Sunday, Granada, a team seriously out of form, will be looking to bounce back when they play bottom club Huesca. The Aragonese are one of very few clubs across Europe's major divisions to still not have recorded a league win. Another club underperforming this campaign is Real Betis. Head coach Manuel Pellegrini is clinging to his position, but all could come tumbling down should they lose to Osasuna. The final two fixtures of the weekend see third-placed Villarreal take on Elche, currently in ninth, before the league leaders wrap up the Matchday 12 action. Real Sociedad have 24 points from their 11 games so far, conceding just five goals in the process. They travel to Alaves, the side that stunned Real Madrid last weekend. Are we in for another humbling? Eduardo Siles loves his Spanish football as much as he loves presenting this show (loads). This week he is once again joined by his compatriot and friend Alvaro Romeo to discuss all things Spanish football. They're getting so competitive with their tips it's like having Cristiano and Messi back together. They're here to analyse, preview and dissect La Liga's Matchday 11 action. For all the latest La Liga odds ahead of this year's finals, head to http://oddspedia.com/football where you'll find everything you need to secure your best bet. Here's what on this week's show: 00:00 Intro 01:00 Athletic Bilbao vs Celta Vigo betting tips and predictions 02:44 Levante vs Getafe betting tips and predictions 04:25 Sevilla vs Real Madrid betting tips and predictions 07:16 Atletico Madrid vs Real Valladolid betting tips and predictions 09:02 Cadiz vs Barcelona betting tips and predictions 11:25 Granada vs Huesca betting tips and predictions 13:33 Osasuna vs Real Betis betting tips and predictions 15:23 Villarreal vs Elche betting tips and predictions 16:52 Alaves vs Real Sociedad setting tips and predictions 19:04 Eibar vs Valencia betting tips and predictions 21:15 La Liga ACCA of the Week Head to http://oddspedia.com for all the latest sports news, data, tips, predictions, best odds and other info to guarantee your best bet. Please like this video, share and subscribe to our channel. Plus, make sure you don't miss any of Oddspedia's new content by clicking the notifications bell. Let's connect: FB | facebook.com/oddspedia TW | twitter.com/oddspedia IG | instagram.com/oddspedia

083 – Who are these Aragonese anyway? With David Cot of “The History of Spain”

Before going into the war of the Italian Vespers, we get some help from David Cot of "The History of Spain" podcast to bring us u to date on the kingdom of Aragon and Peter III and his sons.

Benjamin R. Gampel, “Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392” (Cambridge UP, 2016)

Benjamin R. Gampel‘s award winning volume Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392 (Cambridge University Press, 2016) is the first total history of a lesser known period in Jewish history, overshadowed by the Spanish expulsion of 1492 which it would come to foreshadow. Over the course of ten months, Jews across large parts of the Iberian peninsula were murdered or forced to convert to Christianity, and entire communities were decimated—the intensity and duration of this period mark it as the most devastating attack on the Jews of pre-modern Christian Europe. While many historians have written studies about 1391-92 from isolated perspectives, in the face of an overwhelming number of local archives found throughout the peninsula, and the complexity of those sources, a unified narrative has, until now, remained a desideratum. In this methodological tour-de-force, Professor Gampel tells the story of Spanish Jewry and their relationship to royal power by reading state records and the almost daily correspondence of the royal family against the grain, telling the story of the subjects of these sources imbedded in the thick context of their composers. The book is divided into two sections that mirror its title. The first is a detailed study of the violence of 1391-92 arranged according to the geographic regions of the peninsula—the Kingdoms of Castile, Valencia, and Aragon, Catalonia and the island of Majorca. Using a rich array of archival sources and in dialogue with contemporary historiography, Professor Gampel painstakingly sets out the limits of what we can know about the riots, both of the victims and the perpetrators, detailing each episode chronologically, in order to form a picture of the period as a whole. Central to the book is the question of how and why those tasked with protecting the Jewish communities failed to do so. To this end the second section is centered around three members of the Aragonese royal family—King Joan, Queen Iolant, and Duke Marti—and their response to the violence as it unfolded. Here we see the Jewish community as one of many competing interests the royal family faced, and thereby can better appreciate the contingencies of history. The two sections together provide both a deep macro and micro study of this crucial time in Jewish and Spanish history, exposing us not only to the story and context of the too often voiceless victims, but the lives of those in power as well. Its a narrative of tragic violence and the failure of the Royal Alliance, grounded in extensive historical research stripped of none of its drama. Professor Benjamin R. Gampel is the the Dina and Eli Field Family Chair in Jewish History at The Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. You can hear more from him in his video lecture series on the history, society, and culture of medieval Sephardic Jewry. Moses Lapin is a graduate student in the departments of History and Philosophy at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; his friends call him young Farabi. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Benjamin R. Gampel, “Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392” (Cambridge UP, 2016)

Benjamin R. Gampel‘s award winning volume Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392 (Cambridge University Press, 2016) is the first total history of a lesser known period in Jewish history, overshadowed by the Spanish expulsion of 1492 which it would come to foreshadow. Over the course of ten months, Jews across large parts of the Iberian peninsula were murdered or forced to convert to Christianity, and entire communities were decimated—the intensity and duration of this period mark it as the most devastating attack on the Jews of pre-modern Christian Europe. While many historians have written studies about 1391-92 from isolated perspectives, in the face of an overwhelming number of local archives found throughout the peninsula, and the complexity of those sources, a unified narrative has, until now, remained a desideratum. In this methodological tour-de-force, Professor Gampel tells the story of Spanish Jewry and their relationship to royal power by reading state records and the almost daily correspondence of the royal family against the grain, telling the story of the subjects of these sources imbedded in the thick context of their composers. The book is divided into two sections that mirror its title. The first is a detailed study of the violence of 1391-92 arranged according to the geographic regions of the peninsula—the Kingdoms of Castile, Valencia, and Aragon, Catalonia and the island of Majorca. Using a rich array of archival sources and in dialogue with contemporary historiography, Professor Gampel painstakingly sets out the limits of what we can know about the riots, both of the victims and the perpetrators, detailing each episode chronologically, in order to form a picture of the period as a whole. Central to the book is the question of how and why those tasked with protecting the Jewish communities failed to do so. To this end the second section is centered around three members of the Aragonese royal family—King Joan, Queen Iolant, and Duke Marti—and their response to the violence as it unfolded. Here we see the Jewish community as one of many competing interests the royal family faced, and thereby can better appreciate the contingencies of history. The two sections together provide both a deep macro and micro study of this crucial time in Jewish and Spanish history, exposing us not only to the story and context of the too often voiceless victims, but the lives of those in power as well. Its a narrative of tragic violence and the failure of the Royal Alliance, grounded in extensive historical research stripped of none of its drama. Professor Benjamin R. Gampel is the the Dina and Eli Field Family Chair in Jewish History at The Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. You can hear more from him in his video lecture series on the history, society, and culture of medieval Sephardic Jewry. Moses Lapin is a graduate student in the departments of History and Philosophy at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; his friends call him young Farabi.

Benjamin R. Gampel, “Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392” (Cambridge UP, 2016)

Benjamin R. Gampel‘s award winning volume Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392 (Cambridge University Press, 2016) is the first total history of a lesser known period in Jewish history, overshadowed by the Spanish expulsion of 1492 which it would come to foreshadow. Over the course of ten months, Jews across large parts of the Iberian peninsula were murdered or forced to convert to Christianity, and entire communities were decimated—the intensity and duration of this period mark it as the most devastating attack on the Jews of pre-modern Christian Europe. While many historians have written studies about 1391-92 from isolated perspectives, in the face of an overwhelming number of local archives found throughout the peninsula, and the complexity of those sources, a unified narrative has, until now, remained a desideratum. In this methodological tour-de-force, Professor Gampel tells the story of Spanish Jewry and their relationship to royal power by reading state records and the almost daily correspondence of the royal family against the grain, telling the story of the subjects of these sources imbedded in the thick context of their composers. The book is divided into two sections that mirror its title. The first is a detailed study of the violence of 1391-92 arranged according to the geographic regions of the peninsula—the Kingdoms of Castile, Valencia, and Aragon, Catalonia and the island of Majorca. Using a rich array of archival sources and in dialogue with contemporary historiography, Professor Gampel painstakingly sets out the limits of what we can know about the riots, both of the victims and the perpetrators, detailing each episode chronologically, in order to form a picture of the period as a whole. Central to the book is the question of how and why those tasked with protecting the Jewish communities failed to do so. To this end the second section is centered around three members of the Aragonese royal family—King Joan, Queen Iolant, and Duke Marti—and their response to the violence as it unfolded. Here we see the Jewish community as one of many competing interests the royal family faced, and thereby can better appreciate the contingencies of history. The two sections together provide both a deep macro and micro study of this crucial time in Jewish and Spanish history, exposing us not only to the story and context of the too often voiceless victims, but the lives of those in power as well. Its a narrative of tragic violence and the failure of the Royal Alliance, grounded in extensive historical research stripped of none of its drama. Professor Benjamin R. Gampel is the the Dina and Eli Field Family Chair in Jewish History at The Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. You can hear more from him in his video lecture series on the history, society, and culture of medieval Sephardic Jewry. Moses Lapin is a graduate student in the departments of History and Philosophy at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; his friends call him young Farabi. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Benjamin R. Gampel, “Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392” (Cambridge UP, 2016)

Benjamin R. Gampel‘s award winning volume Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392 (Cambridge University Press, 2016) is the first total history of a lesser known period in Jewish history, overshadowed by the Spanish expulsion of 1492 which it would come to foreshadow. Over the course of ten months, Jews across large parts of the Iberian peninsula were murdered or forced to convert to Christianity, and entire communities were decimated—the intensity and duration of this period mark it as the most devastating attack on the Jews of pre-modern Christian Europe. While many historians have written studies about 1391-92 from isolated perspectives, in the face of an overwhelming number of local archives found throughout the peninsula, and the complexity of those sources, a unified narrative has, until now, remained a desideratum. In this methodological tour-de-force, Professor Gampel tells the story of Spanish Jewry and their relationship to royal power by reading state records and the almost daily correspondence of the royal family against the grain, telling the story of the subjects of these sources imbedded in the thick context of their composers. The book is divided into two sections that mirror its title. The first is a detailed study of the violence of 1391-92 arranged according to the geographic regions of the peninsula—the Kingdoms of Castile, Valencia, and Aragon, Catalonia and the island of Majorca. Using a rich array of archival sources and in dialogue with contemporary historiography, Professor Gampel painstakingly sets out the limits of what we can know about the riots, both of the victims and the perpetrators, detailing each episode chronologically, in order to form a picture of the period as a whole. Central to the book is the question of how and why those tasked with protecting the Jewish communities failed to do so. To this end the second section is centered around three members of the Aragonese royal family—King Joan, Queen Iolant, and Duke Marti—and their response to the violence as it unfolded. Here we see the Jewish community as one of many competing interests the royal family faced, and thereby can better appreciate the contingencies of history. The two sections together provide both a deep macro and micro study of this crucial time in Jewish and Spanish history, exposing us not only to the story and context of the too often voiceless victims, but the lives of those in power as well. Its a narrative of tragic violence and the failure of the Royal Alliance, grounded in extensive historical research stripped of none of its drama. Professor Benjamin R. Gampel is the the Dina and Eli Field Family Chair in Jewish History at The Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. You can hear more from him in his video lecture series on the history, society, and culture of medieval Sephardic Jewry. Moses Lapin is a graduate student in the departments of History and Philosophy at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; his friends call him young Farabi. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Benjamin R. Gampel, “Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391-1392” (Cambridge UP, 2016)