Podcast appearances and mentions of Roger Bacon

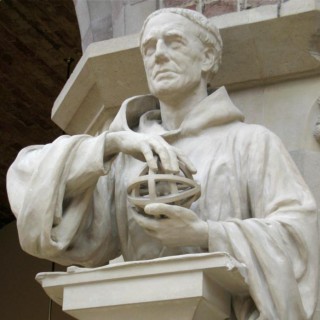

Medieval philosopher and theologian

- 97PODCASTS

- 157EPISODES

- 1h 1mAVG DURATION

- 1EPISODE EVERY OTHER WEEK

- Feb 19, 2026LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about Roger Bacon

Latest news about Roger Bacon

- Changing the Eurocentric narrative about the history of science – why multiculturalism matters English – The Conversation - Apr 9, 2025

- Inside the Plan to Teach Robots the Laws of War The New Republic - Jan 2, 2025

- William of Sherwood Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Sep 27, 2024

- How Henry VIII accidentally changed the way we write history The Conversation – Articles (UK) - Aug 27, 2024

- Headline Origin: Foot Heads Arms Body Quote Investigator - Aug 20, 2024

- An Intoxicating 500-Year-Old Mystery The Atlantic - Aug 8, 2024

- Silicon Valley’s vision for AI? It’s religion, repackaged. Vox - Sep 7, 2023

- England’s weather in 1269 revealed by medieval report Medievalists.net - Aug 22, 2023

- Medieval Maverick: Roger Bacon's Quest for Knowledge and Truth Ancient Origins - Apr 23, 2023

- The Fascinating Life Of Roger Bacon, The 13th-Century ‘Wizard’ Who Helped Pioneer Modern Science All That's Interesting - Mar 7, 2023

Latest podcast episodes about Roger Bacon

David King Dunaway, "A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See" (Bloomsbury, 2026)

Eyeglasses have become so commonplace we hardly think about them—unless we can't find them. Yet glasses have been controversial throughout history. Roger Bacon pioneered using lenses to see and then spent a decade in a medieval prison for advocating that he could fix" God's creations by improving our eyesight. Even today, people take off their glasses before having their picture taken, despite how necessary they are. A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See (Bloomsbury, 2026) is the first book to investigate the experience of wearing glasses and contacts and their role in culture. Dr. David King Dunaway encourages readers to take a look at how they literally see the world through what they wear. He explores everything from the history of deficient eyesight and how glasses are made to portrayals of those who wear glasses in media, the stigma surrounding them, and the future of augmented and virtual reality glasses, highlighting how glasses have shaped, and continue to shape, who we are. Interwoven is Dr. Dunaway's own experience of spending a week without his glasses, which he has used since childhood, to see the world around him and his newfound appreciation for his visual aids. This is the story of how we see the world and how our ability to see things has evolved, ultimately asking: How have two cloudy, quarter-sized discs of crystal or glass originally riveted together become so essential to human existence? Shakespeare famously said eyes are windows to the soul, but what about people who see only by covering theirs with glasses? Readers will find out together through this fascinating and insightful cultural history of one of humanity's greatest inventions. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. You can find Miranda's interviews on New Books with Miranda Melcher, wherever you get your podcasts. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/new-books-network

David King Dunaway, "A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See" (Bloomsbury, 2026)

Eyeglasses have become so commonplace we hardly think about them—unless we can't find them. Yet glasses have been controversial throughout history. Roger Bacon pioneered using lenses to see and then spent a decade in a medieval prison for advocating that he could fix" God's creations by improving our eyesight. Even today, people take off their glasses before having their picture taken, despite how necessary they are. A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See (Bloomsbury, 2026) is the first book to investigate the experience of wearing glasses and contacts and their role in culture. Dr. David King Dunaway encourages readers to take a look at how they literally see the world through what they wear. He explores everything from the history of deficient eyesight and how glasses are made to portrayals of those who wear glasses in media, the stigma surrounding them, and the future of augmented and virtual reality glasses, highlighting how glasses have shaped, and continue to shape, who we are. Interwoven is Dr. Dunaway's own experience of spending a week without his glasses, which he has used since childhood, to see the world around him and his newfound appreciation for his visual aids. This is the story of how we see the world and how our ability to see things has evolved, ultimately asking: How have two cloudy, quarter-sized discs of crystal or glass originally riveted together become so essential to human existence? Shakespeare famously said eyes are windows to the soul, but what about people who see only by covering theirs with glasses? Readers will find out together through this fascinating and insightful cultural history of one of humanity's greatest inventions. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. You can find Miranda's interviews on New Books with Miranda Melcher, wherever you get your podcasts. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/history

David King Dunaway, "A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See" (Bloomsbury, 2026)

Eyeglasses have become so commonplace we hardly think about them—unless we can't find them. Yet glasses have been controversial throughout history. Roger Bacon pioneered using lenses to see and then spent a decade in a medieval prison for advocating that he could fix" God's creations by improving our eyesight. Even today, people take off their glasses before having their picture taken, despite how necessary they are. A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See (Bloomsbury, 2026) is the first book to investigate the experience of wearing glasses and contacts and their role in culture. Dr. David King Dunaway encourages readers to take a look at how they literally see the world through what they wear. He explores everything from the history of deficient eyesight and how glasses are made to portrayals of those who wear glasses in media, the stigma surrounding them, and the future of augmented and virtual reality glasses, highlighting how glasses have shaped, and continue to shape, who we are. Interwoven is Dr. Dunaway's own experience of spending a week without his glasses, which he has used since childhood, to see the world around him and his newfound appreciation for his visual aids. This is the story of how we see the world and how our ability to see things has evolved, ultimately asking: How have two cloudy, quarter-sized discs of crystal or glass originally riveted together become so essential to human existence? Shakespeare famously said eyes are windows to the soul, but what about people who see only by covering theirs with glasses? Readers will find out together through this fascinating and insightful cultural history of one of humanity's greatest inventions. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. You can find Miranda's interviews on New Books with Miranda Melcher, wherever you get your podcasts. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

David King Dunaway, "A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See" (Bloomsbury, 2026)

Eyeglasses have become so commonplace we hardly think about them—unless we can't find them. Yet glasses have been controversial throughout history. Roger Bacon pioneered using lenses to see and then spent a decade in a medieval prison for advocating that he could fix" God's creations by improving our eyesight. Even today, people take off their glasses before having their picture taken, despite how necessary they are. A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See (Bloomsbury, 2026) is the first book to investigate the experience of wearing glasses and contacts and their role in culture. Dr. David King Dunaway encourages readers to take a look at how they literally see the world through what they wear. He explores everything from the history of deficient eyesight and how glasses are made to portrayals of those who wear glasses in media, the stigma surrounding them, and the future of augmented and virtual reality glasses, highlighting how glasses have shaped, and continue to shape, who we are. Interwoven is Dr. Dunaway's own experience of spending a week without his glasses, which he has used since childhood, to see the world around him and his newfound appreciation for his visual aids. This is the story of how we see the world and how our ability to see things has evolved, ultimately asking: How have two cloudy, quarter-sized discs of crystal or glass originally riveted together become so essential to human existence? Shakespeare famously said eyes are windows to the soul, but what about people who see only by covering theirs with glasses? Readers will find out together through this fascinating and insightful cultural history of one of humanity's greatest inventions. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. You can find Miranda's interviews on New Books with Miranda Melcher, wherever you get your podcasts. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/science-technology-and-society

David King Dunaway, "A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See" (Bloomsbury, 2026)

Eyeglasses have become so commonplace we hardly think about them—unless we can't find them. Yet glasses have been controversial throughout history. Roger Bacon pioneered using lenses to see and then spent a decade in a medieval prison for advocating that he could fix" God's creations by improving our eyesight. Even today, people take off their glasses before having their picture taken, despite how necessary they are. A Four-Eyed World: How Glasses Changed the Way We See (Bloomsbury, 2026) is the first book to investigate the experience of wearing glasses and contacts and their role in culture. Dr. David King Dunaway encourages readers to take a look at how they literally see the world through what they wear. He explores everything from the history of deficient eyesight and how glasses are made to portrayals of those who wear glasses in media, the stigma surrounding them, and the future of augmented and virtual reality glasses, highlighting how glasses have shaped, and continue to shape, who we are. Interwoven is Dr. Dunaway's own experience of spending a week without his glasses, which he has used since childhood, to see the world around him and his newfound appreciation for his visual aids. This is the story of how we see the world and how our ability to see things has evolved, ultimately asking: How have two cloudy, quarter-sized discs of crystal or glass originally riveted together become so essential to human existence? Shakespeare famously said eyes are windows to the soul, but what about people who see only by covering theirs with glasses? Readers will find out together through this fascinating and insightful cultural history of one of humanity's greatest inventions. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. You can find Miranda's interviews on New Books with Miranda Melcher, wherever you get your podcasts. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/technology

BİLİMSEL DÜŞÜNCE VE İBN-İ HEYSEM-19 ARALIK 2025-MEVLANA TAKVİMİ

Bilimsel yöntem sayesinde, kozmozdan kuantum, ilmin her alanında büyük buluş-lar yapıldı. Peki bilimsel yöntemi kim buldu derseniz akla Isaac Newton gelir. Galileo ve Descartes diyenler olur. Bilim tarihçilerine so-rarsanız onlar Roger Bacon diyecektir. Ancak konu ile ilgili detaylı araştırma yapanlar, bilim-sel metodun icadını, Roger Bacon'ı da New-ton'u da etkileyen, onlardan 250 yıl önce ya-şamış müslüman bilim adamı İbn-i Heysem'e (965-1040) götürecektir.Bilimsel yöntemin kurucusu İbn-i Heysem şöyle der: “Öğrendiklerini hep eleştiriye tâbi tutacaksın. Yani incelemelerinde, tahkikatında kendi bildiklerinden şüphe edeceksin. Ancak bu sayede önyargı tuzağına düşmekten kur-tulursun.” Ve devam ediyor: “Araştıran kişinin amacı hakikati öğrenmektir. Bunun için öğre-neceklerinin tümünü düşman (yanlış, eksik) göreceksin. Her yönden onu karşına alıp, ona taarruz edeceksin. Bilgiyi ancak bu şekilde fethederek, onu hakikate dönüştürebilirsin.” Heysem'in geliştirdiği bilimsel yöntemin temelinde, yargıları ve bilgileri eleştirmek ve sonuçlar çıkarırken son derece dikkatli olmak vardır. Bildiklerini tekrar tekrar şüphe eleğin-den geçirmek gerekiyor. Burada şüphe ile ilgili Hz. Ali (k.v.)'nin bir sözü aklımıza geliyor. O diyor ki: “Şüphe ikidir. Birinci tür şüphe marazî (şizofrenik) şüphedir. Makbul değildir. Makbul olan, bildiklerini eksik ve yanlış görmekten doğan ikinci tür şüphedir. Seni derin ve etraflı öğrenmeye götürür.”Sadece İbn-i Heysem değil, İbn-i Haldun, Harezmî, er-Razi gibi daha birçok bilim ada-mının bilimsel yöntem tarifine katkıları oldu. Bu zatlar bilim tarihini değiştiren kişilerdir.(Prof. Dr. Osman Çakmak, Zafer Dergisi, 549. Sayı, Eylül 2022)

Roger Bacon "Shank" - Out Of The Frying Pan Wnsdy At 7 "Back Of The Line" www.wnsdyat7.band Fail The Enemy "Paper Dreams" www.failtheenemy.comSirsy "Lot Of Love" - Coming Into Frame www.sirsy.comJoy Buzzer "If You Can Forgive Me" www.joybuzzerband.comMylo Bybee "Time Machine" www.mylobybee.com ************************DVTR "Les Olympiques" - Bonjour www.dvtr.caSadlands "Twin Flame" - Try To Have A Little Fun Calling All Captains "Blood For Blood" The Things That I've Lost www.callingallcaptainsband.comFaraj Risberg Rogefeldt "Rötter" - s/t The Dahmers "Nightmare Of '78" www.dahmers.com Siluett "Blindside" - **********************Scott Sean White "Not The Year"- Even Better On The Bad Days www.scottseanwhite.comKatie Dahl "Both Doors Open" - Seven Stones www.katiedahlmusic.com Julian Taylor (featuring Jim James) "Don't Let 'Em (Get Inside of Your Head) www.juliantaylormuysic.caHelene Cronin "Halfway Back To Knoxville" www.helenecronin.com Switchback "Time Will Have To Wait" - Birds Of Prey www.waygoodmusic.com Closing music: Geoffrey Armes "Vrikshashana (The Tree)" - Spirit Dwelling Running time: 4 hours, 1 minutes. I hold deed to this audio's usage, which is free to share with specific attribution, non-commercial and non-derivation rules.https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Can AI decode the Voynich Manuscript? Part 2/2

Watch the PREVIOUS episode on YouTube!Watch THIS episode on YouTube or click below!TIMELINE00:00 AI Computational Approach13:00 Decoding Voynich19:30 Hoax?21:00 Could women have written it?26:15 What to ask the manuscript's producer27:00 How do we know we've cracked the code?30:00 Reconsidering VoynichEgyptian hieroglyphics confounded Egyptologists for centuries until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone.The Voynich Manuscript is another old text that has perplexed experts since its discovery about 600 years ago.Dr. Robert H. Edwards specializes in investigating the biggest mysteries of the 20th century. I interviewed him on the 100th anniversary of George Mallory's death. I interviewed him again after we found Mallory's climbing partner's foot. Spoiler: We still don't know whether they reached Everest's summit.The other mystery Edwards investigated was D. B. Cooper, who stole $200,000 and disappeared after skydiving.Now, Edwards turns his analytical brain to the world's most mysterious manuscript: the Voynich Manuscript.Voynich Reconsidered: The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World is Dr. Edwards's attempt at decoding this headache-producing document. If you think James Joyce's Finnegans Wake is hard to decipher, try the Voynich Manuscript!Excerpts from Voynich ReconsideredThe parchment for these four folios was most probably produced sometime in the first half of the fourteenth century.Who wrote the Voynich Manuscript?Nobody knows. Edwards debunks the idea that Roger Bacon authored it:D'Imperio devoted considerable effort to the study of the supposed link between the manuscript and Roger Bacon. She could not have known that the Voynich parchment would eventually be submitted to radiocarbon technology and that the samples would be dated, with up to 92 percent probability, to periods ranging between 1308 and 1458. Therefore, she could not have known that Bacon, who lived in the thirteenth century, would be excluded as the author of the manuscript, or at least as its producer or as one of its scribes.Is the Voynich Manuscript a hoax?Before we embark on our own voyage of investigation of the Voynich manuscript, we must consider the alarming possibility that it is a journey to nowhere. That is to say: it may be that the manuscript cannot be translated or deciphered because it has no intrinsic meaning. For want of better words, we must consider that the manuscript could be a hoax or a forgery.What's the Voynich Manuscript about?There is an “herbal” section, consisting of 129 pages and thereby comprising more than half of the book.The astronomical, cosmological, and astrological sections are short. Edwards is “tempted to group them together into a ‘cosmic' theme, occupying thirty-one pages.”The Voynich manuscript invites, for those who are so disposed, the insertion of a preconceived narrative. In this respect, it bears comparison with the notorious proliferation of narratives relating to the man who came to be known as D.B. Cooper, and his hijacking of Northwest Airlines Flight 305 on November 24, 1971.Do we know what the Voynich Manuscript's message is?For many years, the mission controllers at NASA resisted demands for another photographic targeting of the “Face. ” Finally, they relented. In 2001, the Mars Global Surveyor took the first new image of the object, at a much higher resolution than that of the Viking. It was revealed to be an eroded mesa with a pleasing symmetry, and certainly with gulleys and hollows that conveyed elements of a human face. Whether that is the end of the story, the reader may decide. This author is content for the mesa to be the product of erosion, by wind or by water, and not the work of ancient Martians, however much we would like it to be so. Likewise, determined researchers of the Voynich manuscript can find, within its cryptic and inscrutable pages, that which they wish to findConclusionI loved Dr. Edwards's other two books (Mallory & Cooper). Although I liked this one about the Voynich manuscript, it's such an inscrutable and inaccessible document that I found it challenging to stay engaged.Moreover, I don't understand why some people believe that old documents are worth much more than their historical value. Religious texts are helpful because they reveal the values and ideas of the past, but are often utterly wrong, especially when it comes to scientific facts. Even when they're not mistaken, they're often incomplete. A modern botanist knows far more about plants than a 14th-century writer.Some fans of the Voynich manuscript seem to believe that if we can somehow decode it, we'll learn a mind-bending revelation. I doubt it.Other fans, including Dr. Edwards, find the Voynich manuscript fascinating for the same reason people are drawn to Sudoku or a crossword puzzle: it's fun to solve a mystery even if it yields little practical benefit.If you're drawn to puzzles and the Voynich manuscript, you must buy the Voynich Manuscript and then read Voynich Reconsidered: The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World. You're guaranteed to learn countless remarkable facts about the manuscript in Dr. Edwards's splendid and thorough analysis.For others, I'd first start by reading Dr. Edwards's other two books, which are more accessible than this one.Verdict: 7 out of 10 stars.ConnectSend me an anonymous voicemail at SpeakPipe.com/FTaponYou can post comments, ask questions, and sign up for my newsletter at https://wanderlearn.comIf you like this podcast, subscribe and share!On social media, my username is always FTapon. Connect with me on:* Facebook* Twitter* YouTube* Instagram* TikTok* LinkedIn* Pinterest* TumblrSponsors1. My Patrons sponsored this show! Claim your monthly reward by becoming a patron for as little as $2/month at https://Patreon.com/FTapon2. For the best travel credit card, get one of the Chase Sapphire cards and get 75-100k bonus miles!3. Get $5 when you sign up for Roamless, my favorite global eSIM with its unlimited hotspot & data that never expires! Use code LR32K4. Or get 5% off when you sign up with Saily, another global eSIM with a built-in VPN & ad blocker.5. Get 25% off when you sign up for Trusted Housesitters, a site that helps you find sitters or homes to sit in.6. Start your podcast with my company, Podbean, and get one month free!7. In the United States, I recommend trading cryptocurrency with Kraken. 8. Outside the USA, trade crypto with Binance and get 5% off your trading fees!9. For backpacking gear, buy from Gossamer Gear. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit ftapon.substack.com

Mysterious Voynich Manuscript Reconsidered - Part 1/2

Egyptian hieroglyphics confounded Egyptologists for centuries until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone.The Voynich Manuscript is another old text that has perplexed experts since its discovery about 600 years ago.Watch this episode on YouTube to see nonstop images of the book itself!Dr. Robert H. Edwards specializes in investigating the biggest mysteries of the 20th century. I interviewed him on the 100th anniversary of George Mallory's death. I interviewed him again after we found Mallory's climbing partner's foot. Spoiler: We still don't know whether they reached Everest's summit.The other mystery Edwards investigated was D. B. Cooper, who stole $200,000 and disappeared after skydiving.Now, Edwards turns his analytical brain to the world's most mysterious manuscript: the Voynich Manuscript.Voynich Reconsidered: The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World is Dr. Edwards's attempt at decoding this headache-producing document. If you think James Joyce's Finnegans Wake is hard to decipher, try the Voynich Manuscript! Here is my interview about the Voynich Manuscript with Dr. Edwards:Video Excerpts from Voynich ReconsideredThe parchment for these four folios was most probably produced sometime in the first half of the fourteenth century.Who wrote the Voynich Manuscript? Nobody knows. Edwards debunks the idea that Roger Bacon authored it:D'Imperio devoted considerable effort to the study of the supposed link between the manuscript and Roger Bacon. She could not have known that the Voynich parchment would eventually be submitted to radiocarbon technology and that the samples would be dated, with up to 92 percent probability, to periods ranging between 1308 and 1458. Therefore, she could not have known that Bacon, who lived in the thirteenth century, would be excluded as the author of the manuscript, or at least as its producer or as one of its scribes.Is the Voynich Manuscript a hoax?Before we embark on our own voyage of investigation of the Voynich manuscript, we must consider the alarming possibility that it is a journey to nowhere. That is to say: it may be that the manuscript cannot be translated or deciphered because it has no intrinsic meaning. For want of better words, we must consider that the manuscript could be a hoax or a forgery.What's the Voynich Manuscript about?There is an “herbal” section, consisting of 129 pages and thereby comprising more than half of the book.The astronomical, cosmological, and astrological sections are short. Edwards is "tempted to group them together into a 'cosmic' theme, occupying thirty-one pages."The Voynich manuscript invites, for those who are so disposed, the insertion of a preconceived narrative. In this respect, it bears comparison with the notorious proliferation of narratives relating to the man who came to be known as D.B. Cooper, and his hijacking of Northwest Airlines Flight 305 on November 24, 1971.Do we know what the Voynich Manuscript's message is?For many years, the mission controllers at NASA resisted demands for another photographic targeting of the “Face. ” Finally, they relented. In 2001, the Mars Global Surveyor took the first new image of the object, at a much higher resolution than that of the Viking. It was revealed to be an eroded mesa with a pleasing symmetry, and certainly with gulleys and hollows that conveyed elements of a human face. Whether that is the end of the story, the reader may decide. This author is content for the mesa to be the product of erosion, by wind or by water, and not the work of ancient Martians, however much we would like it to be so. Likewise, determined researchers of the Voynich manuscript can find, within its cryptic and inscrutable pages, that which they wish to findConclusionI loved Dr. Edwards's other two books (Mallory & Cooper). Although I liked this one about the Voynich manuscript, it's such an inscrutable and inaccessible document that I found it challenging to stay engaged.Moreover, I don't understand why some people believe that old documents are worth much more than their historical value. Religious texts are helpful because they reveal the values and ideas of the past, but are often utterly wrong, especially when it comes to scientific facts. Even when they're not mistaken, they're often incomplete. A modern botanist knows far more about plants than a 14th-century writer. Some fans of the Voynich manuscript seem to believe that if we can somehow decode it, we'll learn a mind-bending revelation. I doubt it.Other fans, including Dr. Edwards, find the Voynich manuscript fascinating for the same reason people are drawn to Sudoku or a crossword puzzle: it's fun to solve a mystery even if it yields little practical benefit.If you're drawn to puzzles and the Voynich manuscript, you must buy the Voynich Manuscript and then read Voynich Reconsidered: The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World. You're guaranteed to learn countless remarkable facts about the manuscript in Dr. Edwards's splendid and thorough analysis.For others, I'd first start by reading Dr. Edwards's other two books, which are more accessible than this one.Verdict: 7 out of 10 stars.ConnectSend me an anonymous voicemail at SpeakPipe.com/FTaponYou can post comments, ask questions, and sign up for my newsletter at https://wanderlearn.com.If you like this podcast, subscribe and share! On social media, my username is always FTapon. Connect with me on:FacebookTwitterYouTubeInstagramTikTokLinkedInPinterestTumblr Sponsors1. My Patrons sponsored this show! Claim your monthly reward by becoming a patron for as little as $2/month at https://Patreon.com/FTapon2. For the best travel credit card, get one of the Chase Sapphire cards and get 75-100k bonus miles!3. Get $5 when you sign up for Roamless, my favorite global eSIM! Use code LR32K4. Get 25% off when you sign up for Trusted Housesitters, a site that helps you find sitters or homes to sit in.5. Start your podcast with my company, Podbean, and get one month free!6. In the United States, I recommend trading cryptocurrency with Kraken. 7. Outside the USA, trade crypto with Binance and get 5% off your trading fees!8. For backpacking gear, buy from Gossamer Gear. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit ftapon.substack.com

The Magus Book 3 – Biographia Antiqua by Francis Barrett F.R.C.

In this third and final book of The Magus, Francis Barrett turns from magical practice to magical history—presenting a rare and invaluable compendium of the great minds who shaped Western occult philosophy. Book III offers concise biographical accounts of dozens of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance adepts, including Zoroaster, Hermes Trismegistus, Pythagoras, Paracelsus, Roger Bacon, Agrippa,...

05/31/2025 Springfield Shawnee vs Roger Bacon (High School Baseball)

The Division 4 District Final game between the Springfield Shawnee Braves and the Roger Bacon Spartans is now available on demand at no charge!

The saint who ripped reality and rose like a sun. Francis and the apocalyptic fears of chaotic times

Saint Francis was born into a world in a panic. The stabilities of the feudal world had collapsed with the rise of mercantilism. The gap between rich and poor was unsustainable and a new underclass was tearing apart the fabric of society. Then, there were the looming presence of the Mongols to the east and the transformative impact of the Islamic empire to the south - both conquerors plunging Christian Europe into an existential crisis.Doomster prophets, ferocious disputes, wild hopes and messianic saviours were commonplace.So what did the man from Assisi constellate in the extremities of his way of life? Who was this figure, beyond the sentimental portrayal that can so easily eclipse his intense radicalism? This talk explores the discoveries made by his followers - the scientia experimentalist of Roger Bacon, William of Ockham and Duns Scotus whose Franciscanism embraced Aristotelianism. It asks how the contraries embraced by Francis and the impossible path he traced might much matter now.For more on Mark see - www.markvernon.comHis new book is Awake! William Blake and the Power of the Imagination

ASTRONOMİYE YÖN VEREN BİLİM ADAMI: BİTRÛCÎ-23 MAYIS 2025-MEVLANA TAKVİMİ

XII. yüzyılda astronomi alanında öne çıkan Bitrûcî, Kurtuba'nın kuzeyinde bulunan Bîtrûc (Pedroche) şehrinde doğmuştur. Avrupa edebiyatında ise “Alpetragius” adıyla tanınmaktadır. Bitrûcî'nin doğum tarihi kesin olarak bilinmemekle birlikte 13. yüzyılın hemen başlarında vefât ettiği görüşü ağır basmaktadır. Bitrûcî, Klasik Dönem'den başlayarak XIII. yüzyıla kadar tartışmasız bir biçimde egemen olan Batlamyûs astronomisini eleştirmiş, bu doğrultuda hocası İbn-i Tufeyl'in de telkinleriyle “Kitâbü'l-Hey'e (Astronomi Kitâbı)” adlı meşhur eserini kaleme almış ve kendisi de bir sistem kurmuştur. Bitrûcî, İbn-i Bâcce ile başlayan ezZerkâlî, Câbir b. Eflâh ve İbn-i Tufeyl ile devam eden Batlamyûs astronomisinin eleştirilmesi konusunda Endülüs'ün en olgun ismi olmuştur.Batlamyûs, yer merkezli âlem modelini savunmaktaydı. Ona göre yedi gezegen (Ay, Güneş, Merkür, Venüs, Mars, Jüpiter, Satürn), sabit durumda olan yerin çevresinde düzgün ve dairevi bir biçimde hareket ediyordu. Bitrûcî ise gök küreyi dokuz tane kâbul ederek, göğün iç içe duran bütün kürelerinin en üstteki dokuzuncu kürenin etkisiyle hareket ettiğini savunmuştur. Bitrûci'nin bu Aristoteles fiziğine uygun sistemi özellikle İslâm astronomları tarafından kâbul görmüştür. Eseri, 1217'de Michael Scott tarafından Latince'ye çevrilmiştir ve böylece Endülüs dışı Avrupa'ya ulaşma imkânı bulmuştur. Bitrûcî'nin astronomi sistemi 13. Yüzyıl Avrupası'nda büyük yakınlar uyandırmıştır. Bununla birlikte Grosseteste, Albetus Magnus, Roger Bacon ve Nikolas Kopernik gibi isimler de Bitrûcî'nin eserinden ve kullandığı sisteminden faydalanmışlardır.(Erol Çetindal, Endülüs'te YetişenMüslüman Bilim Adamları ve Bilim Dünyasına Katkıları, s.34-36)

Episode 314 - The Book No One Can Read: The Voynich Manuscript Mystery

Episode 314 - The Book No One Can Read: The Voynich Manuscript Mystery A 600-year-old book written in an unknown language, bizarre botanical illustrations that don't exist on Earth, and a possible wizard on the run—this episode dives into the biggest literary mystery of all time. This is the unreadable book, the Voynich Manuscript. We explore its enigmatic origins, the life of rare book collector Wilfred Voynich, and the theories surrounding its possible author, Roger Bacon—a medieval friar with a suspiciously wizard-like reputation. But this isn't just a history lesson—things get personal. Has Corinne been hexed? Could crystals be the answer? And how exactly does the Squonk, the world's saddest cryptid, fit into all of this? From CIA codebreakers and AI decryption attempts to extraterrestrial connections and secret societies, we explore the theories, hoaxes, and paranormal possibilities. Is this a centuries old prank? A journal dropped by an alien (obviously it's this one)? Tune in to find out what is going on with the Voynich Manuscript. Watch the Video Version Here Have ghost stories of your own? E-mail them to us at twogirlsoneghostpodcast@gmail.com New Episodes are released every Sunday at 12am PST/3am EST (the witching hour, of course). Corinne and Sabrina hand select a couple of paranormal encounters from our inbox to read in each episode, from demons, to cryptids, to aliens, to creepy kids... the list goes on and on. If you have a story of your own that you'd like us to share on an upcoming episode, we invite you to email them to us! This episode is sponsored by Thrive Causemetics and Boll & Branch. Celebrate the women in your life with Thrive Causemetics. Luxury beauty that gives back. Right now, you can get an exclusive 20% off your first order at thrivecausemetics.com/TGOG. Now's your chance to change the way you sleep with Boll & Branch. Get 15% off, plus free shipping on your first set of sheets at Bollandbranch.com/tgog. If you enjoy our show, please consider joining our Patreon, rating and reviewing on iTunes & Spotify and following us on social media! Youtube, Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and Discord. Edited and produced by Jaimi Ryan, original music by Arms Akimbo! Disclaimer: the use of white sage and smudging is a closed practice. If you're looking to cleanse your space, here are some great alternatives! Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Salvador García trabajaba de cargador para una compañía de transportes en Madrid, España. Su oficio consistía en descargar los camiones y almacenar la mercancía en grandes bodegas. Con eso tenía para el sustento de su familia. Esa mañana Salvador comenzó temprano su trabajo. Pero era un cargamento descomunal. Se trataba de cajas llenas de monedas. Lamentablemente, por un mal movimiento, se le vino encima una pila de éstas. El hombre maniobró para esquivarla, pero no con suficiente rapidez para librarlo del golpe. Por lo pequeño y flaco que era, Salvador no soportó el peso de tantas monedas encima, en total 410 kilos. El que a un hombre lo aplaste el peso del dinero no es nada fuera de lo común. Al contrario, es algo que sucede todos los días. Lo extraordinario del caso es que lo que aplastó al hombre fue el peso físico del dinero y no el peso mental. ¿Por qué será que hay tanta gente que muere bajo el peso de la obsesión con el dinero? «¡Dinero, dinero! —exclamó Eca de Queiroz, escritor portugués—. ¿Qué no hacen los hombres por el dinero? ¡De todo! Aun vender su alma inmortal.» El apóstol Pablo, en una carta a su discípulo Timoteo, le dice: «Los que quieren enriquecerse caen en la tentación y se vuelven esclavos de sus muchos deseos. Estos afanes insensatos y dañinos hunden a la gente en la ruina y en la destrucción. Porque el amor al dinero es la raíz de toda clase de males. Por codiciarlo, algunos se han desviado de la fe y se han causado muchísimos sinsabores» (1 Timoteo 6:10). Es interesante notar cómo el apóstol describe el peligro del dinero: el amarlo «es la raíz de toda clase de males». ¿Qué es el amor al dinero? Es la pasión obsesionante y enfermiza de querer más y más, de nunca tener lo suficiente. A algunos la obsesión los hace ahorrar y ahorrar sin saber ni para qué. A otros la obsesión los hace gastar y gastar, y de lo que obtienen nunca hay fin. El dinero que en forma desmedida obtenemos, y todo lo que conseguimos que va más allá de nuestras necesidades, nunca bastarán para satisfacer nuestra avaricia. Si sólo anhelamos lo material, viviremos ansiosos toda la vida. De los labios de Roger Bacon, monje inglés de la edad media, salieron las siguientes palabras, que son oro: «El dinero es como el estiércol. Amontonado, apesta, pero desparramado por el mundo, fertiliza.» Sólo cuando Jesucristo es nuestro Señor podemos ser libres de la pasión por el dinero y del peso mortal de la avaricia. Porque Cristo nos da el equilibrio necesario para saber usar el dinero, sin dejarnos dominar por él. Hermano PabloUn Mensaje a la Concienciawww.conciencia.net

Ep #581 - Steve Rossi, CAA and AD at Roger Bacon HS (Ohio)

We're back in Ohio and this time we sit down with Steve Rossi, CAA who is the AD at Roger Bacon H.S. one of the most storied programs in the state! Steve shares his journey along with some Best Practices for ADs on this episode of The Educational AD Podcast! --- Support this podcast: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/educational-ad-podcast/support

The Voynich Manuscript. Dubbed as one of the most mysterious books in the world, the manuscript is a 15th-century codex written in an unknown script and adorned with bizarre and bewildering illustrations. As the boys unpack the manuscript's history, they trace its origins back to the early 1400s, when it was believed to be crafted in Northern Italy during the Italian Renaissance. The episode starts with an exploration of the manuscript's physical attributes. The Voynich Manuscript is famous for its peculiar botanical illustrations that do not match any known plants, astrological diagrams, and surreal scenes. This bizarre content fuels the central mystery: the meaning and purpose of the manuscript, which remains undeciphered despite the efforts of numerous cryptographers and scholars throughout the centuries, including those during both World Wars. The boys discuss various theories about the creator of the Voynich Manuscript. Was it the work of an alchemist? A secret communication between spies? Or perhaps a hoax meant to baffle and mislead? They entertain the idea that it might have been created by Roger Bacon, a medieval philosopher known for his works in the fields of mathematics, astronomy, and languages. This theory intertwines with speculative narratives about the manuscript being intended as a pharmacopeia or a treatise on nature from another world. The boys also discuss more fantastical theories, such as the manuscript being a guidebook from another dimension or an alien artifact left for human discovery. They bring on a linguistics expert to discuss the structure and patterns within the text, examining whether the language could be a cipher, an invented script, or simply gibberish designed to confuse. scientific analyses conducted on the manuscript's parchment and ink, revealing carbon dating results and details about the materials used. This scientific perspective grounds the discussion, bringing a tangible touch to the otherwise mystifying narrative. To conclude, the hosts reflect on the cultural and historical significance of the Voynich Manuscript. They debate its place in history and the possibility that its code might one day be cracked, providing insights into medieval European thought and the human penchant for creating and solving puzzles. Whether a seasoned cryptographer or a casual enthusiast of historical mysteries, listeners will find themselves drawn into the labyrinthine twists and turns of the Voynich Manuscript's story. The episode is not only a journey through a peculiar artifact but also a meditation on the human desire to explore, understand, and, perhaps, ultimately remain baffled by the unknown. Patreon -- https://www.patreon.com/theconspiracypodcast Our Website - www.theconspiracypodcast.com Our Email - info@theconspiracypodcast.com

Ep #566 - David Olson, RAA - Assistant AD at Roger Bacon HS

We visit one of our FAVORITE States today as David Olson, the Assistant AD at Roger Bacon H.S. in Ohio shares his story + Best Practices on The Educational AD Podcast! --- Send in a voice message: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/educational-ad-podcast/message Support this podcast: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/educational-ad-podcast/support

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/new-books-network

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/history

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/medicine

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/european-studies

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/science-technology-and-society

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/christian-studies

Peter Murray Jones, "The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England" (Boydell & Brewer, 2024)

Friars are often overlooked in the picture of health care in late mediaeval England. Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, barbers, midwives - these are the people we think of immediately as agents of healing; whilst we identify university teachers as authorities on medical writings. Yet from their first appearance in England in the 1220s to the dispersal of the friaries in the 1530s, four orders of friars were active as healers of every type. Their care extended beyond the circle of their own brethren: patients included royalty, nobles and bishops, and they also provided charitable aid and relief to the poor. They wrote about medicine too. Bartholomew the Englishman and Roger Bacon were arguably the most influential authors, alongside the Dominican Henry Daniel. Nor should we forget the anonymous Franciscan compilers of the Tabula medicine, a handbook of cures, which, amongst other items, contains case histories of friars practising medicine. Even after the Reformation, these texts continued to circulate and find new readers amongst practitioners and householders. The Medicine of the Friars in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) by Peter Murray Jones restores friars to their rightful place in the history of English health care, exploring the complex, productive entanglement between care of the soul and healing of the body, in both theoretical and practical terms. Drawing upon the surprising wealth of evidence found in the surviving manuscripts, it brings to light individuals such as William Holme (c. 1400), and his patient the duke of York (d. 1402), who suffered from swollen legs. Holme also wrote about medicinal simples and gave instructions for dealing with eye and voice problems experienced by his brother Franciscans. Friars from the thirteenth century onwards wrote their medicine differently, reflecting their religious vocation as preachers and confessors. This interview was conducted by Dr. Miranda Melcher whose new book focuses on post-conflict military integration, understanding treaty negotiation and implementation in civil war contexts, with qualitative analysis of the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/british-studies

Lance recaps the Reds' 1-0 loss to the Pirates today, FC Cincinnati with Pat Brennan of the Enquirer, Roger Bacon underwater hockey head coach Paul Wittekind, Grayson Hodges about his son Burrow Hodges and their gift from the Bengals and Lance takes your calls about who the best living MLB player is after the passing of Willie Mays.

Lance recaps the Reds' 1-0 loss to the Pirates today, FC Cincinnati with Pat Brennan of the Enquirer, Roger Bacon underwater hockey head coach Paul Wittekind, Grayson Hodges about his son Burrow Hodges and their gift from the Bengals and Lance takes your calls about who the best living MLB player is after the passing of Willie Mays.

Lance talks with the head coach of Roger Bacon's underwater hockey team Paul Wittekind

Lance talks with the head coach of Roger Bacon's underwater hockey team Paul Wittekind

04/22/2024 Roger Bacon at Cincinnati Christian (High School Baseball)

The high school baseball game between Roger Bacon and Cincinnati Christian is now available on demand at no charge!

Engines of Our Ingenuity 1153: Grosseteste and Bacon

Episode: 1153 Grosseteste, Bacon, and the rise of realism. Today, Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, and cyberspace.

Father Len explains why we need a Savior now more than ever and why many of us don't know it. Support Wrestling with God Productions: https://www.GiveSendGo.com/WWGProductions Highlights, Ideas, and Wisdom “Now that we have science, we no longer need religion.” – Chris Hayes, MSNBC Host “God of the Gaps” theory: People invented God and religion began because there was a lack of scientific knowledge to explain things like lightning and wind. Science wouldn't exist without the Catholic Church. For the Catholic Church science has always been a way of studying and understanding God. All early major scientists believed in God including Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Roger Bacon, Louis Pasteur, Nicholas Copernicus and Blaise Pascal. They came to God because of science. Many were Catholic priests. Religion began out of gratitude and awe for God. Those who believe there is no greater power in the universe than the human person must ignore humanity's long history of ignorance, violence and shocking denials of the truth. Those who believe science can answer every question won't be able to find God or recognize the need for a Savior because they have too much ego. Our country has a depression and suicide crisis. Our society has become narcissistic. Narcissism steals our joy. Narcissists believe they have no need for a Savior. Much of our country no longer trusts in God. It trusts in science, technology, and government programs. If God doesn't exist and life on earth is all there is, why not cheat, be cruel, or commit suicide? There is a difference between joy and pleasure. Meth addicts have plenty of pleasure, but no joy. Even with all the knowledge of science and the power of technology, we do not have the power to overcome death. “Our country has the highest standard of living in human history and the greatest technological inventions. So, why do we have such high suicide and depression rates? That just proves humanity needs a Savior.” – Father Len We welcome your questions and comments: Email: irish@wwgproductions.org Text or voicemail: 208-391-3738 Links to More Podcasts from Wrestling with God Productions Life Lessons from Jesus and the Church He Founded: http://LifeLessonsfromJesus.org A Priest's Life: https://idahovocations.com/resources/video-podcasts/

In this episode we delve into the life and legacy of the enigmatic Roger Bacon. Once considered a magician with fantastical abilities, Bacon's reputation transformed over the centuries, oscillating between mystical figure and scientific pioneer. Born in 1220, Bacon's journey through Oxford, Paris, and his unexpected entry into the Franciscan order unfolds against the backdrop of a changing Europe. Join us as we explore Bacon's intricate blend of philosophy, optics, and experimental science, shedding light on his revolutionary contributions to the pursuit of knowledge.Contact: thecompletehistoryofscience@gmail.comTwitter: @complete_sciMusic Credit: Folk Round Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License

El más importante científico medieval, promulgaba que la experiencia debía reemplazar a la lógica y predijo que la ciencia iba a toparse con dificultades morales en el futuro.

Comprehensive history of AI episode w/ Max Foley (Reality Gamer) (Harmless AI / Anti-Yudkowski) Original release 8/28/23 the stupidity of E/ACC, RAND corporation 4.0, Van Neumann / Robert Oppenheimer, Game Theory, Corporate Surrealism, Andy Warhol: Cyborg, AI Alignment scam, Bayesian probability, Roger Bacon's Brazen Head, “There is no natural religion”, #BRG, scientific realism, and more... Full episodes, research series, and more here

Fast-Track British English Fluency With News Stories Ep 651

Supercharge Your English Language Fluency: Learn with Trending UK News

Book your astrology readings at: www.jilljardineastrology.com/shopSupport Cosmic Scene with Jill Jardine by becoming a Subscriber!ttps://www.buzzsprout.com/958528/supportWould you like more wealth, prosperity, and love in your life? Would you like to develop your intuition, so you can make better decisions in life? Check out Jill's New on-line courses on Sanskrit Mantras for Wealth, Prosperity, Love and to Develop your intuition!https://jilljardineastrology.com/MCSThis episode is on the Powerful Violet Flame Meditation which begins at 13 minutes into the episode. For the first 13 minutes, Jill explains the significance of the Violet Flame and St. Germain.Also called the “Flame of Transmutation,” the “Flame of Mercy,” the “Flame of Freedom,” and the “Flame of Forgiveness,” the Violet Flame is a sacred fire that transforms and purifies negative “karma” or blockages.The violet flame is a powerful symbol and form of imagery that can be used as a catalyst for our spiritual journeys. The reason for this is that it creates the space necessary for healing any soul blockages.St. Germain is an ascended Master. Ascended Masters are spiritual beings or guides who have ascended to the Higher Dimensions to assist Humanity's evolution from the higher spheres or lokas. They have incarnated on earth previously and now exist in higher realms to help humans. Jesus Christ, Buddha and Krishna are all considered ascended Masters. According to Theosophy and other esoteric spiritual teachings, such as those taught by the late Elizabeth Clare Prophet, there are seven Ascended Masters responsible for the Seven Rays of Evolution, or the Seven Paths to God. According to Elizabeth Clare Prophet “The Seven Color rays are the natural division of the pure white light emanating from the heart of God as it descends through the prism of manifestation. The Seven Rays present seven paths to individual or personal spiritual evolution. Seven masters have mastered identity by walking these paths. These seven masters are called the Chohans of the rays, which mean lord of the rays. Chohan is a Sanskrit term for lord.ST. GERMAIN, the Chohan of the 7th Ray, is the Ascended Master of the Aquarian Age. 7th Ray rules freedom, mercy transmutation and ritual. The pulsations of the violet flame can be felt from his retreat of the House of Rakocsy and Transylvania and from the Cave of Symbols in the United States. St. Germain had many Earthly incarnations including Merlin, the famed magician of Arthurian times in the 5th century, Roger Bacon, Christopher Columbus and Francis Bacon. He was best known as the“le Comte de Saint Germain,” a miraculous gentleman who dazzled the courts of 18th and 19th century Europe, where they called him “The Wonderman.” In that incarnation he was an alchemist, scholar, linguist, poet, musician, and diplomat admired throughout the courts of Europe. In her book, Saint Germain: Mystery of the Violet Flame, Elizabeth Claire Prophet gives this message from St. Germain:"Allow for the Violet Flame that I have released this night to move through your bodies, to transmute all of the tensions of the solar plexus, and allow for the integration of your heart with your own SOUL Presence. And be of Joy and Happiness to know that you have a SOUL Presence that looks after you, that adores you, that is who you are. . . . “Support the show

Three Doctors and a Razor: Medieval English Philosophers

A Subcast episode looking at four of the most influential philosophers working in England during the Middle Ages: Anselm of Canterbury, Roger Bacon, John Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham.Support the showPlease like, subscribe, and rate the podcast on Apple, Spotify, Google, or wherever you listen. Thank you!Email: classicenglishliterature@gmail.comFollow me on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Tik Tok, and YouTube.If you enjoy the show, please consider supporting it with a small donation. Click the "Support the Show" button. So grateful!Podcast Theme Music: "Rejoice" by G.F. Handel, perf. The Advent Chamber OrchestraSubcast Theme Music: "Sons of the Brave" by Thomas Bidgood, perf. The Band of the Irish GuardsSound effects and incidental music: Freesounds.org

The Mongol Storm: Making and Breaking Empires in the Medieval Near East

The most disruptive and transformative event in the Middle Ages wasn't the Crusades, the Battle of Agincourt, or even the Black Death. It was the Mongol Conquests. Even after his death, Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire grew to become the largest in history—four times the size of Alexander the Great's and stretching from the Pacific to the Mediterranean. But the extent to which these conquering invasions and subsequent Mongol rule transformed the diverse landscape of the medieval Near East have been understated in our understanding of the modern world.Today's guest is Nicholas Morton, author of “The Mongol Storm: Making and Breaking Empires in the Middle East.” We discuss the overlapping connections of religion, architecture, trade, philosophy and ideas that reformed over a century of Mongol rule. Rather than a Euro- or even Mongol-centric perspective, this history uniquely examines the Mongol invasions from the multiple perspectives of the network of peoples of the Near East and travelers from all directions—including famous figures of this era such as Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta, Ibn Khaldun, and Roger Bacon, who observed and reported on the changing region to their respective cultures—and the impacted peoples of empires—Byzantine, Seljuk and then Ottoman Turks, Ayyubid, Armenian, and more—under the violence of conquest.

Aristóteles, Galeno, Avicena: traducciones de medicina y filosofía. Mariano Gómez Aranda

Ciclos de conferencias: La Escuela de Traductores de Toledo (III). Aristóteles, Galeno, Avicena: traducciones de medicina y filosofía. Mariano Gómez Aranda. En medicina, los traductores en Toledo optaron por los tratados de Galeno, el gran médico griego del siglo II d. C. Estas obras determinarían en gran medida los fundamentos del funcionamiento de la salud y la enfermedad, proporcionando conceptos fundamentales como la teoría de los cuatro humores (sangre, flema, bilis amarilla y bilis negra) y las cuatro cualidades básicas (calor, frío, humedad y sequedad). También contribuyó al desarrollo de la medicina medieval la traducción del Canon del médico persa Avicena, llevada a cabo por Gerardo de Cremona. Esta obra se convertiría en la Edad Media en el manual básico para el tratamiento de los problemas de salud. Las traducciones de las obras filosóficas de Aristóteles se basaron, en varios casos, en los comentarios a las mismas por parte del filósofo cordobés Averroes, que tamizó el pensamiento del sabio griego a través del filtro de la religión. De esta manera, las teorías aristótelicas adquirieron mayor importancia en el Occidente latino, dando lugar a debates y discusiones acerca de aquellos asuntos más controvertidos desde el punto de vista religioso, como la idea de la eternidad del mundo, que entraba en contradicción con el dogma de la creación de la nada, concepto defendido por musulmanes, judíos y cristianos. La traducción del tratado De anima de Avicena contribuyó a desarrollar la filosofía sobre la psicología humana en Occidente. Varios pensadores cristianos de gran relieve, como Alberto Magno o Roger Bacon, harían uso de los textos de Avicena en sus tratados filosóficos. Explore en canal.march.es el archivo completo de Conferencias en la Fundación Juan March: casi 3.000 conferencias, disponibles en audio, impartidas desde 1975.

On Thursday July 26th, 2018 the Hermetic Hour with host Poke Runyon will discuss the Mysterious Voynich Manuscript (Beinecke MS. 408) a late medieval herbal, alchemical and astrological book written in an unknown language and illustrated with pictures of plants and astronomical arrangements that are not of this world. Authorship was originally attributed to Roger Bacon (1214 - 1292) but carbon-dating placed the MS. in the early fifteenth century. John Dee and Edward Kelley have been suggested because of their similar Enochian language creation, but there is no proof of their involvement. The mysterious MS has fascinated both scholars and amateur researchers alike with solutions announced every year since 1943 when the U.S. Government code-breakers attempted to decipher it. A new solution was announced just a week before this broadcast and has already been discredited. The main reason most experts fail seems obvious to a Hermetic scholar. The Voynich MS was not written in cipher. It was written in a language and in an alphabet that has no analog on earth or in this earthly dimension. The key to finding the origin of the Voynich material might be found in another mysterious manuscript published in 1670. We will read this revelation as our contribution toward solving the mystery -- so put on your Indiana Jones fedora and listen in.

Episode 195 - Elijah/Elisha, Roger Bacon, Matthew Hopkins, Ghost Mirrors, Flying Saucers, Tarrare's Hunger

Or Wood/Cuthbert, Pork Pork, Matty Jumpfamilies, Spectre Reflector, Hovering Teacups, Frenchman's Feast.

Talking 25th Skyline Chili Crosstown Showdown. Roger Bacon coach Mike Blaut joined me to preview the season opener Thursday vs Taft.