Podcasts about John Galsworthy

- 44PODCASTS

- 79EPISODES

- 2h 23mAVG DURATION

- 1MONTHLY NEW EPISODE

- Nov 21, 2025LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about John Galsworthy

Latest news about John Galsworthy

- ‘The Forsytes’ Sets Premiere Date At PBS Masterpiece Deadline - Oct 29, 2025

- THE FORSYTES Starring Joshua Orpin and Millie Gibson | First Look Tom + Lorenzo - Aug 11, 2025

- Ambition in Topanga paradise: Anton Chekhov and John Galsworthy at Theatricum Botanicum L.A. Times - Entertainment News - Jul 16, 2025

- Miss Margaret Morris’ Merry Mermaids Flashbak - Jun 2, 2025

- The Forsyte Saga: 'faultless' production with a 'pitch-perfect' cast BizToc - Oct 31, 2024

- The week in theatre: The Forsyte Saga, Parts 1 and 2; Othello – review Theatre | The Guardian - Oct 27, 2024

- Queen of the remakes! After making her name in on-screen adaptions, Eleanor Tomlinson has turned her hand to reworks - as she was snapped filming new version of The Forsyte Saga Daily Mail - May 21, 2024

- TVLine Items: New Forsyte Saga Series, Dwayne Johnson’s WCW Docu and More TVLine - Apr 30, 2024

- RSPB at 120: the forgotten South American pioneer who helped change Victorian attitudes to birds The Conversation – Articles (UK) - Feb 27, 2024

- The Union Jackal, August 2023 Counter-Currents - Aug 29, 2023

Latest podcast episodes about John Galsworthy

This week the TV Gold podcast with Andrew Mercado and James Manning reviews three series and a Netflix movie. Listen to the podcast: https://pod.link/1106441089 Reckless (SBS, 4 episodes)Two feuding siblings are forced to work together to get away with an accidental hit and run murder that spirals wildly out of control in their hometown of Fremantle. Features a memorable performance from Tasma Walton. The Beast in Me (Netflix, 8 episodes)A famous author is pulled into a twisted mind game with her rich, powerful new neighbour — who just might be a murderer. Claire Danes is back with what is arguably her best role since playing Carrie in Homeland. She stars alongside Matthew Rhys and Brittany Snow. The Forsytes (ABC iview, 6 episodes)Inspired by John Galsworthy's Forsyte Saga novels, The Forsytes chronicles the lives, loves, trials and triumphs of a wealthy late Victorian stockbroking family near the turn of the 20th Century. From the makers of Poldark, this series again stars Eleanor Tomlinson with Jack Davenport co-starring. Frankenstein (Netflix movie)Oscar winner Guillermo del Toro reimagines Mary Shelley's classic tale of a brilliant scientist and the creature his monstrous ambition brings to life.See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Class Divides, Revenge Justice, Paris and more: MASTERPIECE Season Preview (Ep. 76)

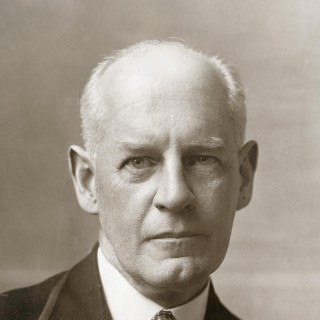

Susanne Simpson, Executive Producer and Head of Scripted Content for MASTERPIECE, the Emmy Award winning PBS drama series, returns to "Historical Drama with The Boston Sisters" for the 5th season preview of MASTERPIECE and MYSTERY! — a podcast annual event since the launch in 2021.In episode 76 Susanne previews new MYSTERY! series coming in the fall 2025 (MAIGRET and THE GOLD), and new historical dramas for MASTERPIECE coming in 2026: THE COUNT OF MONTE CRISTO based on the classic novel by Alexandre Dumas (pere); and THE FORSYTES, a prequel to the THE FORSYTE SAGA, a 2002 MASTERPIECE series based on the trilogy of novels by English author John Galsworthy (1867-1933). TIME STAMPS:0:29 - Podcast summary0:53 - Susanne Simpson intro2:14 - Public media funding and MASTERPIECE4:47 - Previewing 2025 - 20265:00 PBS Passport5:50 - MAIGRET on MYSTERY!10:11 - THE GOLD on MYSTERY!12:26 - THE FORSYTES on MASTERPIECE20:30 - Multiracial casting in THE FORSYTES and historical drama27:30 - THE COUNT OF MONTE CRISTO on MASTERPIECE31:36 - Edmond Dantès, revenge, and justice36:03 - Where to watch MASTERPIECE and MYSTERY!36:37 - Subscribe to Historical Drama with The Boston Sisters37:14 - Disclaimer--------SUBSCRIBE to HISTORICAL DRAMA WITH THE BOSTON SISTERS® on your favorite podcast platformENJOY past podcasts and bonus episodesSIGN UP for our mailing listSUPPORT this podcast SHOP THE PODCAST on our affiliate bookstoreBuy us a Coffee! You can support by buying a coffee ☕ here — buymeacoffee.com/historicaldramasistersThank you for listening!

Ellen Geer (Co-Director of Strife):"You Can Make Cities Out Of Mud"

Dennis is joined via Zoom by actor-director-producer Ellen Geer who is the Producing Artistic Director of one of Dennis's favorite spots in Los Angeles, The Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum in Topange Canyon. Dennis has been going to see plays at the outdoor amphitheater since the early 90's and has seen Ellen perform in scores of shows there as well as seeing just as many that she directed and produced. This season, she co-directed the play Strife by Nobel Prize-winning writer John Galsworthy. The show, about a labor strike in rural Pennsylvania, was written in the early 1900's but feels like it could have been written in 2025. The wealthy board of directors feel like the today's financially insatiable oligarchs and the workers are dealing with the same type of injustices that workers face today. Ellen talks about why she chose Strife for this "Season of Resilience," her own history as an activist and the pleasure of co-directing with her daughter Willow Geer. She also discusses the rich history of her family and the property, which was acquired by her parents in the 1950's when her father, the actor Will Geer, was blacklisted during the McCarthy Era and the entire family was ostracized from Hollywood and their Santa Monica community. In the 1950's-60's, the Botanicum property became a safe place for blacklisted artists to seek refuge and practice their craft. In the 1970's, after Will Geer found fame as Grandpa Walton on The Waltons, the place officially opened to the public as The Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum. Ellen talks about her favorite spot on the property, her encounters with animals like bears, deer, mountain lions and rattlesnakes and the challenges of doing theater in such a unique outdoor place. Other topics include: why her father loved plants, losing all her friends as a child because of the blacklist, Jimmy Stewart being sweet to her on The Jimmy Stewart Show, how the current resistance movement could use some good folk songs, and that time her father taught her that reading Shakespeare could be just as enlightening as going to therapy. www.theatricum.com

One-Act Play Collections - Book 6, Part 2 Title: One-Act Play Collections - Volume 6 Overview: This collection includes ten one-act plays by David Belasco, Arnold Bennett, Hereward Carrington, Lewis Carroll, Lord Dunsany, John Galsworthy, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Maurice Maeterlinck, Anna Bird Stewart, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. The Book Coordinators for this collection were Charlotte Duckett, Michele Eaton, Elizabeth Klett, Loveday, Piotr Nater, Algy Pug, Eden Rea-Hedrick, Todd, and Chuck Williamson. A one-act play is a play that has only one act and is distinct from plays that occur over several acts. One-act plays may consist of one or more scenes. The 20-40 minute play has emerged as a popular subgenre of the one-act play, especially in writing competitions. One-act plays make up the overwhelming majority of Fringe Festival shows including at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The origin of the one-act play may be traced to the very beginning of recorded Western drama: in ancient Greece, Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides, is an early example. The satyr play was a farcical short work that came after a trilogy of multi-act serious drama plays. A few notable examples of one-act plays emerged before the 19th century including various versions of the Everyman play and works by Moliere and Calderon. One act plays became more common in the 19th century and is now a standard part of repertory theatre and fringe festivals. Published: Various Series: One-Act Play Collections List: One-Act Play Collections, Play #13 Author: Various Genre: Plays, Theater, Drama Episode: One-Act Play Collections - Book 6, Part 2 Book: 6 Volume: 6 Part: 2 of 2 Episodes Part: 5 Length Part: 3:02:09 Episodes Volume: 10 Length Volume: 5:52:42 Episodes Book: 10 Length Book: 5:52:42 Narrator: Collaborative Language: English Rated: Guidance Suggested Edition: Unabridged Audiobook Keywords: plays, theater, drama, comedy, hit, musical, opera, performance, show, entertainment, farce, theatrical, tragedy, one-act, stage show Hashtags: #freeaudiobooks #audiobook #mustread #readingbooks #audiblebooks #favoritebooks #free #booklist #audible #freeaudiobook #plays #theater #drama #comedy #hit #musical #opera #performance #show #entertainment #farce #theatrical #tragedy #one-act #StageShow Credits: All LibriVox Recordings are in the Public Domain. Wikipedia (c) Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. WOMBO Dream. Elizabeth Klett.

One-Act Play Collections - Book 6, Part 1 Title: One-Act Play Collections - Volume 6 Overview: This collection includes ten one-act plays by David Belasco, Arnold Bennett, Hereward Carrington, Lewis Carroll, Lord Dunsany, John Galsworthy, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Maurice Maeterlinck, Anna Bird Stewart, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. The Book Coordinators for this collection were Charlotte Duckett, Michele Eaton, Elizabeth Klett, Loveday, Piotr Nater, Algy Pug, Eden Rea-Hedrick, Todd, and Chuck Williamson. A one-act play is a play that has only one act and is distinct from plays that occur over several acts. One-act plays may consist of one or more scenes. The 20-40 minute play has emerged as a popular subgenre of the one-act play, especially in writing competitions. One-act plays make up the overwhelming majority of Fringe Festival shows including at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The origin of the one-act play may be traced to the very beginning of recorded Western drama: in ancient Greece, Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides, is an early example. The satyr play was a farcical short work that came after a trilogy of multi-act serious drama plays. A few notable examples of one-act plays emerged before the 19th century including various versions of the Everyman play and works by Moliere and Calderon. One act plays became more common in the 19th century and is now a standard part of repertory theatre and fringe festivals. Published: Various Series: One-Act Play Collections List: One-Act Play Collections, Play #12 Author: Various Genre: Plays, Theater, Drama Episode: One-Act Play Collections - Book 6, Part 1 Book: 6 Volume: 6 Part: 1 of 2 Episodes Part: 5 Length Part: 2:50:33 Episodes Volume: 10 Length Volume: 5:52:42 Episodes Book: 10 Length Book: 5:52:42 Narrator: Collaborative Language: English Rated: Guidance Suggested Edition: Unabridged Audiobook Keywords: plays, theater, drama, comedy, hit, musical, opera, performance, show, entertainment, farce, theatrical, tragedy, one-act, stage show Hashtags: #freeaudiobooks #audiobook #mustread #readingbooks #audiblebooks #favoritebooks #free #booklist #audible #freeaudiobook #plays #theater #drama #comedy #hit #musical #opera #performance #show #entertainment #farce #theatrical #tragedy #one-act #StageShow Credits: All LibriVox Recordings are in the Public Domain. Wikipedia (c) Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. WOMBO Dream. Elizabeth Klett.

One-Act Play Collections - Book 3, Part 2 Title: One-Act Play Collections - Volume 3 Overview: This collection of ten one-act dramas features plays by Edward Goodman, Alice Gerstenberg, Arnold Bennett, John Galsworthy, Anton Chekhov, Frank Wedekind, Moliere, Theresa Helburn, John Kendrick Bangs, and Harold Brighouse. A one-act play is a play that has only one act and is distinct from plays that occur over several acts. One-act plays may consist of one or more scenes. The 20-40 minute play has emerged as a popular subgenre of the one-act play, especially in writing competitions. One-act plays make up the overwhelming majority of Fringe Festival shows including at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The origin of the one-act play may be traced to the very beginning of recorded Western drama: in ancient Greece, Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides, is an early example. The satyr play was a farcical short work that came after a trilogy of multi-act serious drama plays. A few notable examples of one-act plays emerged before the 19th century including various versions of the Everyman play and works by Moliere and Calderon. One act plays became more common in the 19th century and is now a standard part of repertory theatre and fringe festivals. Published: Various Series: One-Act Play Collections List: One-Act Play Collections, Play #6 Author: Various Genre: Plays, Theater, Drama Episode: One-Act Play Collections - Book 3, Part 2 Book: 3 Volume: 3 Part: 2 of 2 Episodes Part: 5 Length Part: 3:27:06 Episodes Volume: 10 Length Volume: 5:45:58 Episodes Book: 10 Length Book: 5:45:58 Narrator: Collaborative Language: English Rated: Guidance Suggested Edition: Unabridged Audiobook Keywords: plays, theater, drama, comedy, hit, musical, opera, performance, show, entertainment, farce, theatrical, tragedy, one-act, stage show Hashtags: #freeaudiobooks #audiobook #mustread #readingbooks #audiblebooks #favoritebooks #free #booklist #audible #freeaudiobook #plays #theater #drama #comedy #hit #musical #opera #performance #show #entertainment #farce #theatrical #tragedy #one-act #StageShow Credits: All LibriVox Recordings are in the Public Domain. Wikipedia (c) Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. WOMBO Dream. Arielle Lipshaw.

One-Act Play Collections - Book 3, Part 1 Title: One-Act Play Collections - Volume 3 Overview: This collection of ten one-act dramas features plays by Edward Goodman, Alice Gerstenberg, Arnold Bennett, John Galsworthy, Anton Chekhov, Frank Wedekind, Moliere, Theresa Helburn, John Kendrick Bangs, and Harold Brighouse. A one-act play is a play that has only one act and is distinct from plays that occur over several acts. One-act plays may consist of one or more scenes. The 20-40 minute play has emerged as a popular subgenre of the one-act play, especially in writing competitions. One-act plays make up the overwhelming majority of Fringe Festival shows including at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The origin of the one-act play may be traced to the very beginning of recorded Western drama: in ancient Greece, Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides, is an early example. The satyr play was a farcical short work that came after a trilogy of multi-act serious drama plays. A few notable examples of one-act plays emerged before the 19th century including various versions of the Everyman play and works by Moliere and Calderon. One act plays became more common in the 19th century and is now a standard part of repertory theatre and fringe festivals. Published: Various Series: One-Act Play Collections List: One-Act Play Collections, Play #5 Author: Various Genre: Plays, Theater, Drama Episode: One-Act Play Collections - Book 3, Part 1 Book: 3 Volume: 3 Part: 1 of 2 Episodes Part: 5 Length Part: 2:18:56 Episodes Volume: 10 Length Volume: 5:45:58 Episodes Book: 10 Length Book: 5:45:58 Narrator: Collaborative Language: English Rated: Guidance Suggested Edition: Unabridged Audiobook Keywords: plays, theater, drama, comedy, hit, musical, opera, performance, show, entertainment, farce, theatrical, tragedy, one-act, stage show Hashtags: #freeaudiobooks #audiobook #mustread #readingbooks #audiblebooks #favoritebooks #free #booklist #audible #freeaudiobook #plays #theater #drama #comedy #hit #musical #opera #performance #show #entertainment #farce #theatrical #tragedy #one-act #StageShow Credits: All LibriVox Recordings are in the Public Domain. Wikipedia (c) Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. WOMBO Dream. Arielle Lipshaw.

One-Act Play Collections - Book 2, Part 2 Title: One-Act Play Collections - Volume 2 Overview: This collection of eight one-act dramas features plays by Eugene O'Neill, George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy, Susan Glaspell, William Dean Howells, and John Millington Synge. It also includes a dramatic reading of a short story by Frank Richard Stockton. A one-act play is a play that has only one act and is distinct from plays that occur over several acts. One-act plays may consist of one or more scenes. The 20-40 minute play has emerged as a popular subgenre of the one-act play, especially in writing competitions. One-act plays make up the overwhelming majority of Fringe Festival shows including at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The origin of the one-act play may be traced to the very beginning of recorded Western drama: in ancient Greece, Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides, is an early example. The satyr play was a farcical short work that came after a trilogy of multi-act serious drama plays. A few notable examples of one-act plays emerged before the 19th century including various versions of the Everyman play and works by Moliere and Calderon. One act plays became more common in the 19th century and is now a standard part of repertory theatre and fringe festivals. Published: Various Series: One-Act Play Collections List: One-Act Play Collections, Play #4 Author: Various Genre: Plays, Theater, Drama Episode: One-Act Play Collections - Book 2, Part 2 Book: 2 Volume: 2 Part: 2 of 2 Episodes Part: 4 Length Part: 2:03:59 Episodes Volume: 8 Length Volume: 4:22:04 Episodes Book: 8 Length Book: 4:22:04 Narrator: Collaborative Language: English Rated: Guidance Suggested Edition: Unabridged Audiobook Keywords: plays, theater, drama, comedy, hit, musical, opera, performance, show, entertainment, farce, theatrical, tragedy, one-act, stage show Hashtags: #freeaudiobooks #audiobook #mustread #readingbooks #audiblebooks #favoritebooks #free #booklist #audible #freeaudiobook #plays #theater #drama #comedy #hit #musical #opera #performance #show #entertainment #farce #theatrical #tragedy #one-act #StageShow Credits: All LibriVox Recordings are in the Public Domain. Wikipedia (c) Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. WOMBO Dream. Elizabeth Klett.

One-Act Play Collections - Book 2, Part 1 Title: One-Act Play Collections - Volume 2 Overview: This collection of eight one-act dramas features plays by Eugene O'Neill, George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy, Susan Glaspell, William Dean Howells, and John Millington Synge. It also includes a dramatic reading of a short story by Frank Richard Stockton. A one-act play is a play that has only one act and is distinct from plays that occur over several acts. One-act plays may consist of one or more scenes. The 20-40 minute play has emerged as a popular subgenre of the one-act play, especially in writing competitions. One-act plays make up the overwhelming majority of Fringe Festival shows including at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The origin of the one-act play may be traced to the very beginning of recorded Western drama: in ancient Greece, Cyclops, a satyr play by Euripides, is an early example. The satyr play was a farcical short work that came after a trilogy of multi-act serious drama plays. A few notable examples of one-act plays emerged before the 19th century including various versions of the Everyman play and works by Moliere and Calderon. One act plays became more common in the 19th century and is now a standard part of repertory theatre and fringe festivals. Published: Various Series: One-Act Play Collections List: One-Act Play Collections, Play #3 Author: Various Genre: Plays, Theater, Drama Episode: One-Act Play Collections - Book 2, Part 1 Book: 2 Volume: 2 Part: 1 of 2 Episodes Part: 4 Length Part: 2:18:08 Episodes Volume: 8 Length Volume: 4:22:04 Episodes Book: 8 Length Book: 4:22:04 Narrator: Collaborative Language: English Rated: Guidance Suggested Edition: Unabridged Audiobook Keywords: plays, theater, drama, comedy, hit, musical, opera, performance, show, entertainment, farce, theatrical, tragedy, one-act, stage show Hashtags: #freeaudiobooks #audiobook #mustread #readingbooks #audiblebooks #favoritebooks #free #booklist #audible #freeaudiobook #plays #theater #drama #comedy #hit #musical #opera #performance #show #entertainment #farce #theatrical #tragedy #one-act #StageShow Credits: All LibriVox Recordings are in the Public Domain. Wikipedia (c) Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. WOMBO Dream. Elizabeth Klett.

In this episode we discuss Hitchcock's early talkie, The Skin Game. Based on a popular play at the time, this 1931 drama deals with the feud between two wealthy families in England. Details: The Skin Game was released in 1931 by British International Pictures. Produced by John Maxwell. Script was written by Alfred Hitchcock and Alma Reville based on John Galsworthy's play. Starring Edmund Gwenn, Helen Haye, C.V. France, Jill Esmond, and Phyllis Konstam. Cinematography by John M. Cox. Ranking: 46 out of 52. Ranking movies is a reductive parlor game. It's also fun. And it's a good way to frame a discussion. We aggregated over 70 ranking lists from critics, fans, and magazines, and will be going through Alfred Hitchcock's films from “worst” to “best.” The Skin Game got 411 ranking points.

FOOTPRINTS ON THE CEILING A SHERLOCK HOLMES PASTICHE by JULWS CASTIER

1001 Sherlock Holmes Stories & The Best of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

There are hundreds of Sherlock Holmes stories written by other authors, but only a handful are in the public domain. This one was written by Jules Castier wile in a German prison during WWI and published in 1920. The story was a part of a collection of pastiches Castier wrote mimicking famous authors of the time- and the publisher wrote to each author asking for a foreword- many responded. The book is rare- it is titled 'Rather Like....Some Endeavors to Assume the Mantle of the Great . In this podcast I ask anyone who gets the book to let us know which authors wrote forewards and to share a few with us- my email: 1001storiespodcast@gmail.com. Authors parodied are : F. Anstey, Arnold Bennett, Hall Caine, G. K. Chesterton, Joseph Conrad, Marie Corelli, Arthur Conan Doyle, John Galsworthy, Charles Garvice, Sir H. Rider Haggard, Henry Harland, Maurice Hewlett, Robert Hichens, E. W. Hornung, W. W. Jacobs, Henry James, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling, William Le Queux, W. J. Locke, Jack London, Leonard Merrick, Henry Seton Merriman, Henry Newbolt, Eden Philpotts, R. W. Service, George Bernard Shaw, Robert Louis Stevenson, Elizabeth von Arnim, E. Temple Thurston, Horace A. Vachell, H. G. Wells, Oscar Wilde and C. N. & A. M. Williamson. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Joyce, Proust, Woolf och Eliot präglar modernismens gyllene år 1922. Men allt fokus på detta år har varit skadligt och gjort litteraturen mindre än vad den är, menar litteraturvetaren Paul Tenngart. ESSÄ: Detta är en text där skribenten reflekterar över ett ämne eller ett verk. Åsikter som uttrycks är skribentens egna.Det är ett välkänt faktum att flera av huvudfigurerna under modernismens viktigaste år, 1922, aldrig fick Nobelpriset i litteratur: James Joyce, Marcel Proust och Virginia Woolf – alla saknas de på listan över stockholmsprisade världsförfattare. Det är väl egentligen bara T.S. Eliot som både bidrog till de legendariska litterära experimenten 1922 och belönades av Svenska Akademien, även om han fick vänta i tjugofem år efter det att The Waste Land publicerades innan han fick priset 1948.Dessa luckor har gett upphov till stark kritik genom årens lopp, ibland rentav föraktfullt hån. Oförmågan att belöna Joyce, Proust och Woolf har setts som belägg för att Svenska Akademien är en inskränkt och obsolet sammanslutning långt ute – eller långt uppe – i den kulturella och geografiska periferin som aldrig borde ha fått uppdraget att dela ut världens viktigaste litterära pris.Vem var det då som fick Nobelpriset 1922? Jo, det gick förstås inte till någon modernist, utan till ett av de idag allra mest bortglömda författarskapen i prisets historia, den spanske dramatikern Jacinto Benavente. Benaventes realistiska dramatik förhåller sig på ett direkt sätt till samtidens sociala frågor och strävar efter en naturlig, icke-teatral dialog. Författarskapet ligger med andra ord långt ifrån högmodernismens eruption av formella experiment.Den litteraturhistoria som Nobelpriserna tecknar är en annan än den vanliga. Men det innebär inte att den är felaktig eller destruktiv. Tvärtom: Nobelprisets parallella historia ger ett lika uppfriskande som konstruktivt – ja, kanske rentav nödvändigt relativiserande – alternativ till den litteraturhistoriska normen.Det är ju faktiskt inte givet att den litteratur som Joyce, Proust, Woolf och Eliot producerade 1922 är bättre än all annan litteratur. Litterära värden är ju knappast naturgivna. Det blir inte minst tydligt när man tittar på vilka Nobelpris som har hyllats och vilka som har kritiserats genom åren. Beslutet att ge schweizaren Carl Spitteler 1919 års pris har i efterhand kritiserats i flera omgångar av internationella bedömare. Men på åttiotalet framstod detta överraskande val som ett av Svenska Akademiens allra bästa. Ett av de pris som de flesta har tyckt om men som enstaka kritiker har fnyst åt är T.S. Eliots. ”Framtiden kommer att skratta”, menade litteraturprofessorn Henri Peyre från Yale University 1951, ”åt det brist på perspektiv i vår tid som gör att vi uppfattar Eliot som en litterär talang av högsta rang.”Den västeuropeiska modernismen – med året 1922 som kronologiskt epicentrum – har under en lång tid lagt sig som en gigantisk blöt filt över hela den internationella litteraturhistorieskrivningen. Vad som hände under det tidiga 20-talet i Paris och London har blivit en grundmurad norm: då och där skrevs det bästa av det bästa. Aldrig tidigare och aldrig senare har litteraturen varit så modern. Hmm.Som inget annat år i världshistorien har universitetskurser och läroböcker tjatat sönder 1922 och dess litterära utgivning. Denna historieskrivning är inte bara slö och slentrianmässig, den är också ordentligt förminskande av en hel modern världshistoria där det skrivits litteratur på alla platser, på alla språk och i alla genrer.Denna kronologiska normativitet har också med all önskvärd tydlighet hjälpt till att gång på gång bekräfta och upprätthålla den västerländska kulturella hegemonin. Som den franska världslitteraturforskaren Pascale Casanova skriver: Västeuropa och USA har kommit att äga det moderna. Moderniteten har kommit att definieras som västerländsk, och det som definierats som modernt har betraktats som per definition bra. De få texter och författarskap som lyfts in i den moderna världslitteraturen från andra delar av världen har fått sin plats där för att de påminner om fransk, brittisk eller amerikansk modernism.Den här normativa litteraturhistorieskrivningen ger också en väldigt sned uppfattning om hur litteratur existerar i världen, och hur den utvecklas och förändras. Det var ju knappast så att läsarna 1922 hängde på låsen till bokhandlarna för att skaffa Joyces nya 900-sidiga experiment Ulysses och T.S. Eliots notförsedda friversdikt The Waste Land så fort dessa texter anlände från trycket. Nä, 1922 var de flesta läsande människor upptagna med andra författare, till exempel sådana som fick Nobelpriset under den perioden: den franske sedesskildraren Anatole France, den norska författaren till historiska romaner Sigrid Undset eller den italienska skildraren av sardiniskt folkliv Grazia Deledda.Än mer brett tilltalande var den litteratur som prisades på trettiotalet, då många kritiker i efterhand har tyckt att Svenska Akademien borde ha kunnat ha vett och tidskänsla nog att ge de inte helt lättillgängliga modernisterna Paul Valéry eller John Dos Passos priset. Då belönades istället Forsythe-sagans skapare John Galsworthy, då fick Roger Martin du Gard priset för sin stora realistiska romansvit om familjen Thibault, och då belönades Erik Axel Karlfeldt – som inte var någon gigant ute i världen, det medges, men mycket omtyckt av många svenska läsare.Det är också under den här tiden som det mest hånade av alla litterära Nobelpris delas ut, till Pearl S. Buck. Men Buck har fått en renässans på senare år. Hon var visserligen från USA, men levde stora delar av sitt liv i Kina och förde med sina lantlivsskildringar in det stora landet i öster i den prisvinnande litteraturen. Och i sin motivering lyfte Nobelkommittéen fram just dessa världsvidgande egenskaper: den amerikanska författarens romaner är ”avgjort märkliga genom äkthet och rikedom i skildringen och sällsynt kunskap och insikt i en för västerländska läsare föga känd och mycket svårtillgänglig värld”. Buck ger inblick i nya kulturella sammanhang, berikar den kulturellt sett högst begränsade västerländska litteraturen med motiv och tematik från en mångtusenårig kultur med en minst lika gedigen litterär tradition som den europeiska.Vad hade hänt om Nobelpriset istället hade gett postuma pris till Rainer Maria Rilke och Marcel Proust, och hunnit belöna Joyce och Woolf innan de dog i början av fyrtiotalet? Rilke, Proust, Joyce och Woolf hade ju knappast kunnat vara större och mer centrala än de redan är. Ingen skillnad där alltså. Men det hade varit mycket svårare för oss att hitta fram till Buck, du Gard, Galsworthy, Deledda, France – och till 1922 års stora litterära namn när det begav sig: Jacinto Benavente. Utan pris hade de alla varit helt undanskymda, osynliga, bortglömda. Nu ser vi dem fortfarande, tack vare den alternativa historieskrivning som Nobelprisets löpande och oåterkalleliga kanonisering skapar. Paul Tenngart, litteraturvetare och författareModernismåret 192227.1 Kafka påbörjar "Slottet".2.2 James Joyces "Ulysses" publiceras.Rainer Maria Rilke får feeling. På tre veckor skriver han hela "Sonetterna till Orfeus" samt avslutar "Duino-elegierna".18.5 Proust, Joyce, Stravinsky, Picasso, Satie med flera äter middag.18.10 BBC Startar26.10 Virginia Woolfs "Jacob's room" publiceras.18.11 Proust dör.15.12 T S Eliots "The waste land" utkommer i bokform.Andra händelser: Karin Boyes debutdiktsamling "Moln" utkommer; Katherine Mansfields "The garden party and other stories" publiceras; Birger Sjöbergs "Fridas bok" utkommer; F Scott Fitzgerald har ett produktivt år (det är också under 1922 som "Den store Gatsby", publicerad 1925, utspelar sig); Prousts "På spaning efter den tid som flytt" börjar publiceras på engelska; i december blir Hemingways portfölj med flera års skrivande stulen på Gare de Lyon.FototVirginina Woolf: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Virginia_Woolf_1927.jpgJame Joyce: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_Joyce_by_Alex_Ehrenzweig,_1915_cropped.jpgT S Eliot:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:T_S_Elliot_-_Mar_1923_Shadowland.jpg

Abril Si te gusta lo que escuchas y deseas apoyarnos puedes dejar tu donación en PayPal, ahí nos encuentras como @IrvingSun 1. Los Buddenbrook – Thomas Mann 2. El sabueso de los Baskerville – Arthur Conan Doyle 3. El corazón de las tinieblas – Joseph Conrad 4. Cañas y barro – Vicente Blasco Ibáñez 5. El inmoralista – André Gide 6. Los embajadores – Henry James 7. El enigma de las arenas – Erskine Childers 8. La llama de la selva – Jack London 9. Sucesos memorables de un enfermo de los nervios – Daniel P. Shreber 10. Sonatas – Ramón María del Valle Inclán 11. Adriano VII – Frederick Rolfe 12. Nostromo – Joseph Conrad 13. La casa de la alegría – Edith Wharton 14. El profesor Unrat – Heinrich Mann 15. Solitud – Víctor Catalá 16. Los extravíos del colega Törless – Robert Musil 17. La saga de los Forsyle – John Galeworthy --- Send in a voice message: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/irving-sun/message

Beyond

Four Short Plays by John Galsworthy

Four Short Plays

A Family Man : in three acts by John Galsworthy

A Family Man : in three acts

The Forsyte Saga, Volume I. by John Galsworthy

The Forsyte Saga, Volume I. The Man Of Property

The Country House by John Galsworthy

The Country House

The Complete Essays of John Galsworthy

The Complete Essays of John Galsworthy

The Island Pharisees by John Galsworthy

The Island Pharisees

Strife: A Drama in Three Acts by John Galsworthy

Strife: A Drama in Three Acts

The Skin Game (A Tragi-Comedy) by John Galsworthy

The Skin Game (A Tragi-Comedy)

Joy: A Play on the Letter "I" by John Galsworthy

Joy: A Play on the Letter "I"

The Mob: A Play in Four Acts by John Galsworthy

The Mob: A Play in Four Acts

The Forsyte Saga, Volume III. by John Galsworthy

The Forsyte Saga, Volume III. Awakening To Let

The Forsyte Saga, Volume II. by John Galsworthy

The Forsyte Saga, Volume II. Indian Summer of a Forsyte In Chancery

The Forsyte Saga by John Galsworthy

Tonight's sleep story is The Forsyte Saga by John Galsworthy. Published between 1906 and 1921, the books follow the Forsyte family, a "new money" upper middle class family navigating London society in the late 1870s to the early 20th century. In this episode, members of the Forsyte family gather to meet (and inspect) a possible new addition to the family.Interested in more sleepy content or just want to support the show? Join Just Sleep Premium here: https://justsleeppodcast.com/supportAs a Just Sleep Premium member you will receive:Ad-free and Intro-free episodesThe entire back catalogue of the podcast, ad and intro-freeThe entire audiobook of the Wizard of OzA collection of short fairy tales including Rapunzel and the Frog PrinceThe chance to vote on the next story that you hearThe chance to win readings just for youThanks for your support!Sweet Dreams...Intro Music by the Psychedelic Squirrel Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

March 20 2023 The Witch Daily Show (https://www.witchdailyshow.com) is talking Eostre Our sponsor today Is Witch Way Magazine (https://www.witchwaymag.com/) and ( Want to buy me a cup of coffee? Venmo: TonyaWitch - Last 4: 9226 Our quote of the day Is: ― “It was such a spring day as breathes into a man an ineffable yearning, a painful sweetness, a longing that makes him stand motionless, looking at the leaves or grass, and fling out his arms to embrace he knows not what.” ― John Galsworthy, The Forsyte Saga Headlines: (https://ny.eater.com/2023/1/23/23566279/foul-witch-robertas-opening-review) Other Sources: (https://www.tragicbeautiful.com/en-us/products/peppermint-herbal-alchemy) Thank you so much for joining me this morning, if you have any witch tips, questions, witch fails, or you know of news I missed, visit https://www.witchdailyshow.com or email me at thewitchdailypodcast@gmail.com If you want to support The Witch Daily Show please visit our patreon page https://www.patreon.com/witchdailyshow Mailing Address (must be addressed as shown below) Tonya Brown 3436 Magazine St #460 New Orleans, LA 70115

‘The Descent of Money: Literature, Inheritance, and Trust in Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth (1905) and John Galsworthy's The Man of Property (1906)'Rob Hawkes' paper argues that Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth (1905) and John Galsworthy's The Man of Property (1906) foreground, interrogate and enact questions of trust, both in their engagements with and departures from literary realism/naturalism and in their preoccupations with the value and power of money. Wharton's novel is saturated with the language of costs, payments, investments, and debts, while the first of Galsworthy's Forsyte novels presents ‘Forsyteism' as an inescapable set of hereditary traits. Both texts, furthermore, implicitly associate money with nature and imagine a ‘sense of property' as inherited in more ways than one, whilst simultaneously offering glimpses of a different understanding of money altogether: one that reveals surprising connections between literature, money, and trust.Visit our Patreon page here: https://www.patreon.com/MoLsuperstructure

Virginia Woolfs "Jacob's Room" betraktas ofta som en förstudie till hennes verkliga storverk. Det är dags att ändra på den uppfattningen, säger litteraturvetaren Karin Nykvist. ESSÄ: Detta är en text där skribenten reflekterar över ett ämne eller ett verk. Åsikter som uttrycks är skribentens egna.Vem är Jacob? Var är Jacob? Jag läser Virginia Woolfs roman Jacobs Room och frågorna kommer till mig, gång på gång. För jag får liksom inte kläm på honom, han glider hela tiden undan.Jag är inte ensam om att känna så. Redan på romanens första sida frågar sig hans mamma: var är den där besvärlige lille pojken? och skickar iväg hans bror för att leta. Ja-cob! Ja-cob! ropar brodern så som så många fler ska göra innan den korta berättelsen är slut.För inte är det mycket vi reda på om Jacob. Istället får vi veta vad andra tänker: när de betraktar honom, förälskar sig i honom, skriver brev om honom och skvallrar om honom. Huvudpersonen själv förblir ett slags gäckande frånvaro, även om vi följer tätt i hans spår: från en dag på stranden i den tidiga barndomen, till studierna i Cambridge, till rummet i London, till le grand tour i Italien och Grekland, och sist till det slutgiltiga försvinnandet, i det första världskrigets stora anonyma död.Så blir romanen till ett slag antibiografi: den tecknar fram ett liv som förblir preludier och skisser; den är en bildningsroman som inte går i mål.Och just däri ligger förstås dess storhet. För vad kan vi veta om en annan människa, eller ens om oss själva? Och hur kan vi fånga det där som är människans mest grundläggande begränsning och samtidigt hennes största och enda möjlighet: livet självt?Romanen är Virginia Woolfs tredje. Den kom ut under det år som ofta blir kallat vidunderligt när litteraturhistoria ska skrivas: 1922. Ur ett engelskspråkigt perspektiv är det nästan Året med stort Å. I februari gav James Joyce ut sin tegelsten Ulysses med hjälp av den modiga Sylvia Beach i Paris. I oktober publicerade T.S Eliot The Waste Land i sin egen tidskrift The Criterion. Och senare samma månad lät paret Woolf trycka upp Jacobs Room på det egna förlaget Hogarth Press.Virginia Woolf kallade själv Jacobs Room för ett experiment, och möjligen är det detta uttalande som får författaren Lawrence Norfolk att i förordet till min engelska utgåva utbrista att romanen saknar det självförtroende som kännetecknar Joyces och Eliots böcker. Självklart har han fel. För det första har en roman inga känslor alls. För det andra och så klart är detta viktigare kräver experimentet en stark och trygg självkänsla. Och det verkar inte som om Woolf skulle darrat på pennan någonstans eller på något sätt valt en försiktig väg här. Några år tidigare - 1919 hade hon skrivit så här om litteraturens nya uppgift: Låt oss skriva ner atomerna så som de dyker upp i vårt sinne, i den ordning de kommer, låt oss följa mönstret, hur osammanhängande och motsägelsefullt det än ter sig, som varje syn eller händelse ristar på medvetandet.Om Virginia Woolfs romaner saknade intrig var det för att livet självt saknar det: bättre då att registrera sinnenas intryck, som bildkonstnären.Woolf menade att litteraturen befann sig vid en skiljeväg, då, i början av tjugotalet. Själv stod hon för det nya, det som mer autentiskt och ärligt förmådde gestalta tillvaron. På andra sidan placerade hon författare som John Galsworthy han som skrev Forsytesagan och som snart skulle få Nobelpriset eller den framgångsrika Arnold Bennett, som skrev böcker i en traditionellt realistisk stil med tydliga huvudpersoner och en allvetande berättare och som till skillnad från Woolf sålde i drivor.Bennett var för övrigt en av alla dem som sågade Jacobs Room. Han menade att romanens gestalter omöjligt kunde få liv hos läsaren eftersom författaren, som han syrligt skrev var besatt av originalitet och smarthet.Woolf skulle snart hämnas och formulera sitt förslag på en ny estetik för romanen: i essän Mrs Brown and Mr Bennett från 1923 skriver hon om hur en tänkt kvinna på ett tåg, Mrs Brown, kan skildras litterärt på olika sätt beroende på författarens övertygelser. Woolf låter där den daterade Mr Bennett och hans gelikar tynga ner den stackars Mrs Brown till oigenkännlighet med en omständlig prosa, trots att hon förtjänar att gestaltas på ett helt annat sätt. Vi måste lära oss att stå ut med det krampaktiga, det obscena, det fragmentariska, misslyckandet, skriver Virginia Woolf. Något annat skulle vara att svika Mrs Brown.Här finns alltså en litteratursyn som bygger på en helt ny människosyn. I Virginia Woolfs värld kan ingen kan längre fångas in, paketeras, eller ges prydlig gestaltning. För att lyckas måste litteraturen misslyckas. Så kan världen skildras sant.Många kritiker har i efterhand betraktat Jacobs room som en förövning till de verkligt stora verken i Woolfs författarskap: hon skulle snart komma att skriva Mrs Dalloway och To the Lighthouse, Mot fyren..Men Jacobs Room är en storartad roman i sin egen rätt Och faktiskt är det den enda av Woolfs romaner som översattes till svenska medan hon själv levde bara en sån sak.Romanens grundtes är att även om vi i sällsynta ögonblick kan uppleva att vi verkligen ser och känner någon så är dessa stunder av absolut närvaro oerhört sällsynta. Istället är det frånvaron som kännetecknar våra liv och våra mänskliga mellanhavanden. Vi skriver, ringer, talar med, till och om varandra, utan att riktigt nå fram. Våra intryck av den rikt myllrande världen är flyktiga och övergående, även om de är fyllda av aldrig så mycket akut skönhet och känsla. Så kan de här stunderna skildras litterärt på samma sätt som impressionisterna tecknade solens förflyttningar över vatten: bara ögonblicket kan fångas, det undflyende.Den som vill filmatisera Jacobs Room borde ha ett lätt jobb: texten består av korta scener som avlöser varandra: vi är på stranden, så - klipp -vid Piccadilly, och klipp - på ett tåg på väg till Cambridge. Och så klipp på Akropolis i Aten.Och överallt alla dessa människor. Inte mindre än 156 namngivna personer befolkar Woolfs roman. Flera av dem får inte ens en halv sida. Alla dessa liv, som vi inte vet någonting om. Och där nånstans, ibland, Jacob, med en bok under armen.1922 var ett storartat litterärt år. Men alla de storverk som skrevs då gick de flesta förbi: både Woolf och Eliot ägnade sig ju åt egenutgivning i små upplagor, och Joyces Ulysses kom ut på ett litet och okänt förlag långt från den engelskspråkiga sfären. Jag läser vidare om Jacob. Och tänker på dagens litterära utgivning. Vilka böcker kommer att vara framtidens omistliga klassiker vilka författare den framtida historieskrivningens fixstjärnor? Ges de också ut på egna och obskyra förlag?Det enda vi säkert vet är att vi har absolut ingen aning. Men jag är allt lite avundsjuk på dem som i framtiden får läsa årets bästa böcker. Vår tids Jacobs Room.Karin Nykvist, litteraturvetare och kritikerFotnot: Jacob's Room finns översatt till svenska som Jacobs Rum av Siri Thorngren-Olin.

Un Día Como Hoy 14 de Agosto Nace: 1867: John Galsworthy, novelista y dramaturgo británico, premio Nobel de Literatura en 1932 (f. 1933). Fallece: 1951: William Randolph Hearst, periodista y editor estadounidense (n. 1863). 1981: Karl Böhm, director de orquesta y músico austriaco (n. 1894). 1994: Elías Canetti, escritor búlgaro nacionalizado británico, premio Nobel de Literatura en 1981 (n. 1905).

Joyce, Proust, Woolf och Eliot präglar modernismens gyllene år 1922. Men allt fokus på detta år har varit skadligt och gjort litteraturen mindre än vad den är, menar litteraturvetaren Paul Tenngart. ESSÄ: Detta är en text där skribenten reflekterar över ett ämne eller ett verk. Åsikter som uttrycks är skribentens egna.Det är ett välkänt faktum att flera av huvudfigurerna under modernismens viktigaste år, 1922, aldrig fick Nobelpriset i litteratur: James Joyce, Marcel Proust och Virginia Woolf alla saknas de på listan över stockholmsprisade världsförfattare. Det är väl egentligen bara T.S. Eliot som både bidrog till de legendariska litterära experimenten 1922 och belönades av Svenska Akademien, även om han fick vänta i tjugofem år efter det att The Waste Land publicerades innan han fick priset 1948.Dessa luckor har gett upphov till stark kritik genom årens lopp, ibland rentav föraktfullt hån. Oförmågan att belöna Joyce, Proust och Woolf har setts som belägg för att Svenska Akademien är en inskränkt och obsolet sammanslutning långt ute eller långt uppe i den kulturella och geografiska periferin som aldrig borde ha fått uppdraget att dela ut världens viktigaste litterära pris.Vem var det då som fick Nobelpriset 1922? Jo, det gick förstås inte till någon modernist, utan till ett av de idag allra mest bortglömda författarskapen i prisets historia, den spanske dramatikern Jacinto Benavente. Benaventes realistiska dramatik förhåller sig på ett direkt sätt till samtidens sociala frågor och strävar efter en naturlig, icke-teatral dialog. Författarskapet ligger med andra ord långt ifrån högmodernismens eruption av formella experiment.Den litteraturhistoria som Nobelpriserna tecknar är en annan än den vanliga. Men det innebär inte att den är felaktig eller destruktiv. Tvärtom: Nobelprisets parallella historia ger ett lika uppfriskande som konstruktivt ja, kanske rentav nödvändigt relativiserande alternativ till den litteraturhistoriska normen.Det är ju faktiskt inte givet att den litteratur som Joyce, Proust, Woolf och Eliot producerade 1922 är bättre än all annan litteratur. Litterära värden är ju knappast naturgivna. Det blir inte minst tydligt när man tittar på vilka Nobelpris som har hyllats och vilka som har kritiserats genom åren. Beslutet att ge schweizaren Carl Spitteler 1919 års pris har i efterhand kritiserats i flera omgångar av internationella bedömare. Men på åttiotalet framstod detta överraskande val som ett av Svenska Akademiens allra bästa. Ett av de pris som de flesta har tyckt om men som enstaka kritiker har fnyst åt är T.S. Eliots. Framtiden kommer att skratta, menade litteraturprofessorn Henri Peyre från Yale University 1951, åt det brist på perspektiv i vår tid som gör att vi uppfattar Eliot som en litterär talang av högsta rang.Den västeuropeiska modernismen med året 1922 som kronologiskt epicentrum har under en lång tid lagt sig som en gigantisk blöt filt över hela den internationella litteraturhistorieskrivningen. Vad som hände under det tidiga 20-talet i Paris och London har blivit en grundmurad norm: då och där skrevs det bästa av det bästa. Aldrig tidigare och aldrig senare har litteraturen varit så modern. Hmm.Som inget annat år i världshistorien har universitetskurser och läroböcker tjatat sönder 1922 och dess litterära utgivning. Denna historieskrivning är inte bara slö och slentrianmässig, den är också ordentligt förminskande av en hel modern världshistoria där det skrivits litteratur på alla platser, på alla språk och i alla genrer.Denna kronologiska normativitet har också med all önskvärd tydlighet hjälpt till att gång på gång bekräfta och upprätthålla den västerländska kulturella hegemonin. Som den franska världslitteraturforskaren Pascale Casanova skriver: Västeuropa och USA har kommit att äga det moderna. Moderniteten har kommit att definieras som västerländsk, och det som definierats som modernt har betraktats som per definition bra. De få texter och författarskap som lyfts in i den moderna världslitteraturen från andra delar av världen har fått sin plats där för att de påminner om fransk, brittisk eller amerikansk modernism.Den här normativa litteraturhistorieskrivningen ger också en väldigt sned uppfattning om hur litteratur existerar i världen, och hur den utvecklas och förändras. Det var ju knappast så att läsarna 1922 hängde på låsen till bokhandlarna för att skaffa Joyces nya 900-sidiga experiment Ulysses och T.S. Eliots notförsedda friversdikt The Waste Land så fort dessa texter anlände från trycket. Nä, 1922 var de flesta läsande människor upptagna med andra författare, till exempel sådana som fick Nobelpriset under den perioden: den franske sedesskildraren Anatole France, den norska författaren till historiska romaner Sigrid Undset eller den italienska skildraren av sardiniskt folkliv Grazia Deledda.Än mer brett tilltalande var den litteratur som prisades på trettiotalet, då många kritiker i efterhand har tyckt att Svenska Akademien borde ha kunnat ha vett och tidskänsla nog att ge de inte helt lättillgängliga modernisterna Paul Valéry eller John Dos Passos priset. Då belönades istället Forsythe-sagans skapare John Galsworthy, då fick Roger Martin du Gard priset för sin stora realistiska romansvit om familjen Thibault, och då belönades Erik Axel Karlfeldt som inte var någon gigant ute i världen, det medges, men mycket omtyckt av många svenska läsare.Det är också under den här tiden som det mest hånade av alla litterära Nobelpris delas ut, till Pearl S. Buck. Men Buck har fått en renässans på senare år. Hon var visserligen från USA, men levde stora delar av sitt liv i Kina och förde med sina lantlivsskildringar in det stora landet i öster i den prisvinnande litteraturen. Och i sin motivering lyfte Nobelkommittéen fram just dessa världsvidgande egenskaper: den amerikanska författarens romaner är avgjort märkliga genom äkthet och rikedom i skildringen och sällsynt kunskap och insikt i en för västerländska läsare föga känd och mycket svårtillgänglig värld. Buck ger inblick i nya kulturella sammanhang, berikar den kulturellt sett högst begränsade västerländska litteraturen med motiv och tematik från en mångtusenårig kultur med en minst lika gedigen litterär tradition som den europeiska.Vad hade hänt om Nobelpriset istället hade gett postuma pris till Rainer Maria Rilke och Marcel Proust, och hunnit belöna Joyce och Woolf innan de dog i början av fyrtiotalet? Rilke, Proust, Joyce och Woolf hade ju knappast kunnat vara större och mer centrala än de redan är. Ingen skillnad där alltså. Men det hade varit mycket svårare för oss att hitta fram till Buck, du Gard, Galsworthy, Deledda, France och till 1922 års stora litterära namn när det begav sig: Jacinto Benavente. Utan pris hade de alla varit helt undanskymda, osynliga, bortglömda. Nu ser vi dem fortfarande, tack vare den alternativa historieskrivning som Nobelprisets löpande och oåterkalleliga kanonisering skapar. Paul Tenngart, litteraturvetare och författareModernismåret 192227.1 Kafka påbörjar "Slottet".2.2 James Joyces "Ulysses" publiceras.Rainer Maria Rilke får feeling. På tre veckor skriver han hela "Sonetterna till Orfeus" samt avslutar "Duino-elegierna".18.5 Proust, Joyce, Stravinsky, Picasso, Satie med flera äter middag.18.10 BBC Startar26.10 Virginia Woolfs "Jacob's room" publiceras.18.11 Proust dör.15.12 T S Eliots "The waste land" utkommer i bokform.Andra händelser: Karin Boyes debutdiktsamling "Moln" utkommer; Katherine Mansfields "The garden party and other stories" publiceras; Birger Sjöbergs "Fridas bok" utkommer; F Scott Fitzgerald har ett produktivt år (det är också under 1922 som "Den store Gatsby", publicerad 1925, utspelar sig); Prousts "På spaning efter den tid som flytt" börjar publiceras på engelska; i december blir Hemingways portfölj med flera års skrivande stulen på Gare de Lyon.FototVirginina Woolf: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Virginia_Woolf_1927.jpgJame Joyce: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_Joyce_by_Alex_Ehrenzweig,_1915_cropped.jpgT S Eliot: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:T_S_Elliot_-_Mar_1923_Shadowland.jpg

Episode 384 - English Lit - Ancient Vip's - Beatles Songs - Play This - Mtv Movie Awards: Best Kiss

Welcome to the Instant Trivia podcast episode 384, where we ask the best trivia on the Internet. Round 1. Category: English Lit 1: During his "Travels" , he visited the flying island of Laputa. Gulliver. 2: This Bronte sister died 1 year after the publication of her second novel, "The Tenant of Wildfell Hall". Anne Bronte. 3: She introduced Mr. and Mrs. Dalloway in her first novel, "The Voyage Out". Virginia Woolf. 4: On this fictional Sir Thomas More island, the interests of the individual are subordinate to those of society. Utopia. 5: This author of "The Forsyte Saga" published his first novel, "Jocelyn", under the pen name John Sinjohn. John Galsworthy. Round 2. Category: Ancient Vip's 1: Books about him were written by Plato and Xenophon, both students of his. Socrates. 2: This Hebrew king taxed his people into rebellion, which may not have been too wise. Solomon. 3: The period during which he ruled is often referred to as "The Golden Age of Athens". Pericles. 4: Uncle of Caligula and stepfather of Nero, this Roman emperor was poisoned by his wife, Nero's mother. Claudius. 5: In the 6th century B.C., he conquered Babylon and made Persia the greatest empire in the world. Cyrus the Great. Round 3. Category: Beatles Songs 1: Originally, this title woman was called Miss Daisy Hawkins, but that didn't sound lonely enough. Eleanor Rigby. 2: For Paul McCartney, this Beatles song title will become true on June 18, 2006. "When I'm Sixty-Four". 3: (Alex: Alright, let's go to Cheryl at the Santa Monica Pier for this) Today, we're all living in a yellow submarine; the Beatles found this colorful body of water in the song. Sea of Green. 4: "Let me hear your balalaikas ringing out, come and keep your comrade warm" here, the title of a '68 song. "Back in the U.S.S.R.". 5: He's "As blind as he can be, just sees what he wants to see". "Nowhere Man". Round 4. Category: Play This 1: This "avian" skateboarding legend has produced several high-flying video games for Activision. Tony Hawk. 2: It's off to Skull Island for Peter Jackson's official video game adaptation of this ape movie. King Kong. 3: In New Super Mario Bros., Mario can go head-to-head against this brother of his. Luigi. 4: Advent Children and Chains of Promethia are just 2 of the many episodes in this popular role-playing game. Final Fantasy. 5: DDR for short, this groovy game can help keep you in shape. Dance Dance Revolution. Round 5. Category: Mtv Movie Awards: Best Kiss 1: Gwyneth Paltrow and Joseph Fiennes won for this movie in 1999. Shakespeare in Love. 2: For a 2003 win, she locked lips with an upside-down Tobey Maguire in "Spider-Man". Kirsten Dunst. 3: (Hi, I'm Vivica Fox) In 1997 this actor and I won the MTV Movie Award for "Best Kiss" for the kiss we shared in "Independence Day". Will Smith. 4: 1998's winner's were Adam Sandler and Drew Barrymore for this film. The Wedding Singer. 5: Woody Harrelson and Demi Moore won for this 1994 film. Indecent Proposal. Thanks for listening! Come back tomorrow for more exciting trivia!

DESCRIPCIÓN LIBROS 00:02:20 La diosa blanca (Robert Graves) 00:06:15 Where the drowned girls go (Seanan McGuire) 00:09:40 El ascenso de la sombra. La rueda del tiempo #4 (Robert Jordan) 00:13:00 A la caza del amor (Nancy Mitford) 00:16:45 Fin de capítulo. Crónicas de de los Forsyte 7-9 (John Galsworthy) 00:22:35 El ocupante (Sarah Waters) DEL PAPEL A LA PANTALLA 00:25:45 Umbrella Academy PELÍCULAS 00:32:15 Death to 2021 00:35:30 Harry Potter 20th anniversary: return to Hogwarts 00:41:25 West Side Story (1961) 00:45:00 Silent night (2021) 00:49:45 The tender bar 00:51:50 Ghostbuster: Afterlife (2021) 00:54:00 No matarás 00:57:35 El poder del perro 01:00:15 El otro guardaespaldas 2 SERIES 01:06:00 Dexter: new blood 01:11:45 Landscapers 00:16:05 Whatt happened, Brittany Murphy 01:21:00 Raphaelismo 01:24:50 Yellowjackets (T1) 01:30:15 Un escándalo muy británico (T2) 01:33:45 Venga Juan (T3) 01:36:10 After life (T3) 01:39;40 A discovery of witches (T3) 01:41:30 Deberes: ACS Impeatchment 01:45:50 DESPEDIDA En este programa suenan: Radical Opinion (Archers) / Siesta (Jahzzar) / From the Back (Pat Lock & Party Pupils) / Place on Fire (Creo) / I saw you on TV (Jahzzar) / Bicycle Waltz (Goodbye Kumiko)

Poem of the Day To Winter William Blake Beauty of Words Evolution John Galsworthy

Daily Quote If you are working on something that you really care about, you don't have to be pushed. The vision pulls you. (Steve Jobs) Poem of the Day To Winter William Blake Beauty of Words Evolution John Galsworthy

PRESENTACIÓN LIBROS 00:02:20 Por si las voces vuelven (Angel Martín) 00:04:50 La broma infinita (David Foster Wallace) 00:10:45 Las piñas de la ira (Cathon) 00:12:00 Tiempos Precarios (Flavia Blondi) 00:15:00 Cassandra Darke (Posy Simmonds) 00:17:25 El fantasma de Anya (Vera Brosgoi) 00:19:00 Hay algo matando niños vol 1 & 2 (James Tynion & Werther Dell'Edera) 00:20:45 Nada. Novela gráfica (Claudio Stassi) 00:22:25 ¡Prepárate! (Vera Brosgoi) 00:24:50 Berlín, 1, 2 & 3 (Jason Lutes) 00:27:00 Strange Planet: The Sneaking, Hiding, Vibrating Creature (Nathan W Pyle) 00:29:15 Blue Lust. Vol 1-3 (Hinako) 00:31:45 La conferencia de los pájaros (miss Peregrine #5) 00:34:40 El canto del cisne. Crónicas de los Forsyte #6 (John Galsworthy) 00:36:50 Little moments of love - Snug - In love and pajamas (Catana Chetwynd) 00:38:50 Los límites de la Fundación. Fundación #6 (Isaac Asimov) 00:43:50 Deberes: Enseñanza Mágica Obligatoria. Vol 1-6 PELÍCULAS 00:46:00 Earwig y la bruja 00:48:50 Zoey's extraordinary Christmas 00:51:35 El caballero verde 00:54:20 The last duel 00:58:30 Madres paralelas 01:02:05 Orgullo y prejuicio y zombies 01:04:05 Spencer 01:07:15 Harold y Maude 01:09:05 Qué duro es el amor 01:10:25 Last night in Soho 01:12:50 Donde caben dos SERIES 01:15:15 Amor con fianza 01:18:40 El juego del calamar 01:21:20 ¿Dónde está Marta? 01:23:35 La vida sexual de las universitarias (T1) 01:26:25 Tiger King (T2) 01:28:15 The walking dead world beyond (T2) 01:32:40 The Great (T2) 01:34:55 La casa de papel (T5.2) 01:38:30 Fear the walking dead (T7) 01:40:40 Deberes: Vida perfecta (T2) / Brooklyn 99 (T8) / American Horror Story (T10) / The bite (T1) En este programa suenan: Radical Opinion (Archers) / Siesta (Jahzzar) / Place on fire (Creo) / I saw you on TV (Jahzzar) / Bicycle Waltz (Goodbye Kumiko)

PRESENTACIÓN LIBROS 00:02:05 Giganta (Jc Deveney & Núria Tamarit) 0:03:30 Una mujer un voto (Alicia Palmer & Montse Mazorriaga) 00:05:05 solas en Berlín (Nicolas Junker) 00:05:25 Laura y Dino (Alberto Mont) 00:09:35 Oryx y Crake & El año del diluvio. MaddAddam #1, #2 (Margaret Atwood) 00:13:25 el fuego nunca se apaga (Noelle Stevenson) 00:15:05 El dragón renacido. La rueda del tiempo #3 (Robert Jordan) 00:18:15 The Avant-Guards (Carly Uslin) 00:19:45 El portal de los obeliscos. La tierra desfragmentada #2 (N.K Jemisin) 00:22:05 Villanueva (Javi de Castro) 00:24:05 El destino del Tearling #3 (Erika Johansen) 00:26:00 La receta de la luna (Suzanne Walker) 00:28:45 La cuchara de plata. Crónicas de los Forsyte #5 (John Galsworthy) 00:30:20 Matemos al tío (Rohan O'Grady) 00:33:00 en un rincón del cielo nocturno & Lluvia al amanecer. Vol #1 & #2 (Nojico Hayakawa) 00:36:25 Agatha Raisin y el veterinario cruel (M.C. Beaton) 00:38:30 Deberes: laura Dean me ha vuelto a dejar (Mariko Tamaki) PELÍCULAS 00:40:55 Eternals 00:47:10 Tick, tick... boom! 00:53:40 Fuimos canciones 00:57:50 Dear Evan Hansen 01:00:30 El cover 01:02:00 The night house 01:03:40 Alerta Roja SERIES 01:06:20 Dolores: La verdad sobre el caso Wanninkhof 01:12:30 The bite 01:15:10 Ana Bolena 01:18:05 Y, the last man 01:21:10 Foundation (T1) 01:26:30 the Morning Show (T2) 01:29:55 Stargirl (T2) 01:31:35 Vida perfecta (T2) 01:34:50 American Crime Story (T3) 01:39:15 What we do in the shadows (T3) 01:42:50 Supergirl (T6) 01:45:45 Last week tonight with John Oliver (T8) COSAS QUE NOS HACEN FELICES 01:49:10 All too well ten minute version, the short film & I bet you think about me (Taylor Swift) 01:56:00 DESPEDIDA En este programa suenan: Radical Opinion (Archers) / Siesta (Jahzzar) / Pace on Fire (Creo) / I saw you on TV (Jahzzar) / Parisian (Kevin MacLeod) / Bicycle Waltz (Goodbye Kumiko)

PRESENTACIÓN LIBROS 00:02:50 How to save a life (Lynette Rice) 00:07:50 La gran cacería. La rueda del tiempo #2 (Robert Jordan) 00:11:00 La quinta estación. La tierra fragmentada #1 (N.K. Jesmin) 00:16:00 La invasión del Tearling #2 (Erika Johansen) 00:18:50 A tumba abierta (Joe Hill) 00:20:50 Billy Summers (Stephen King) 00:23:30 La herencia (Matthew López) 00:28:50 La muerte espera en Herons Park (Christianna Brand) 00:31:00 Canción del ocaso. Trilogía Escocesa #1 (Lewis Grassig Gibbon) 00:35:30 El mono blanco. Crónicas de los Forsyte #4 (John Galsworthy) 00:30:20 Testamento de juventud (Vera Brittain) 00:43:25 Por el bien del comandante (Constance Fenimore Woolson) 00:46:10 Oddball (Sarah Andersen) 00:48:15 Deberes: Carta blanca (Jordi Lafebre) PELÍCULAS 00:50:50 El cuento de la princesa Kaguya 00:54:00 El cuento de Marnie 00:57:40 Everybody's talking about Jamie 01:01:45 Diana: the musical 01:04:20 Britney vs Spears (2021) 01:09:50 Deberes: Old / Free Guy /Cinderella SERIES 01:15:25 La asistenta 01:17:35 Midnight Mass 01:20:10 Insiders 01:23:25 Secretos de un matrimonio 01:26:15 El tiempo que te doy 01:28:05 Only murders in the building (T1) 01:32:10 What if (T1) 01:34:20 Ted Lasso (T2) 01:37:20 The movies that made us (T2) 01:39:25 Evil (T2) 01:44:00 The goes wrong show (T2) 01:46:00 Truth be told (T2) 01:49:00 Locke & Key (T2) 01:51:55 You (3) 01:57:15 Queridos blancos (T4) 01:59:15 Riverdale (T5) 02:01:25 American horror story (T10) 02:05:00 The walking dead (T11A) 02:07:25 Deberes: American horror stories PODCASTS 02:09:45 Otra españolada 02:10:40 La ruina 02:11:45 Crónicas chulapas 02:13:20 DESPEDIDA En este programa suenan: Radical Opinion (Archers) / Siesta Jahzzar) / Place on fire (Creo / I saw you on TV (Jahzzar) / Parisian (Kevin MacLeod) / Bicycle Waltz (Goodbye Kumiko)

Histoire des sagas de "La Dynastie des Forsyte" au cycle Harry Potter

durée : 00:32:53 - Les Nuits de France Culture - par : Philippe Garbit - Nuit des sagas - Entretien 3/4 avec Anne Besson et Catherine Rihoit qui, pour la première, évoque les sagas dans la littérature jeunesse de fantasy et de science-fiction et, pour la seconde, la quintessence du genre avec "La Dynastie des Forsyte", saga victorienne de John Galsworthy. - invités : Catherine Rihoit auteur.; Anne Besson Professeur en Littérature comparée, UFR Lettres et Arts, Université d'Artois.

Jens Falk kommer äntligen tillbaka efter åtta månaders frånvaro från Poddarnas Podd. John Galsworthy får till sist sin dag i rampljuset och Jens delar med sig av sina bästa investeringstips.

John Galsworthy's satirical discussion between himself and a college chum, now a repressed Church of England minister, on the puzzling definition of "Christian" marriage. If, in male-dominated Victorian society, God particularly rewards "suffering", in a "failed" marriage who is more deserving, the socially unconstrained husband or the narrowly restricted wife? And whose role is it, to judge? Adapted by Lance Davis. Performed by PNT Company members John Rafter Lee (Ken Follett Audiobooks) and Lance Davis. Sound by Dave Bennett. (13 minutes) --- Support this podcast: https://anchor.fm/pntradio/support

George Orwell's The Road To Wigan Pier (1937) On Class & Power