Podcast appearances and mentions of Curtis Williams

- 43PODCASTS

- 85EPISODES

- 46mAVG DURATION

- ?INFREQUENT EPISODES

- Oct 29, 2025LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about Curtis Williams

Latest news about Curtis Williams

- Akron vs. Tulane Prediction: Spread, Total Points, Moneyline Picks – Saturday, December 6, 2025 Bleacher Nation | Chicago Sports News, Rumors, and Obsession - Dec 6, 2025

- Williams To Ride Green Wave Yahoo! Sports - Apr 30, 2025

- Digital avatars have arrived: Here’s how real estate pros can use them Inman - Aug 28, 2024

- Black Music Sunday: Revisiting R&B 'one-hit wonders,' decade by decade Daily Kos - Sep 25, 2022

Latest podcast episodes about Curtis Williams

The Current LIVE - Episode 9: Ron Hunter & Curtis Williams; Ashley Langford & Amira Mabry; Jake Retzlaff & Geordan Guidry

Tulane basketball is here! We get ready for the season as Corey Gloor sits down with men's basketball coach Ron Hunter, who discusses his team's journey to opening night after heartbreak in the summer. New forward Curtis Williams breaks down what his skill set will do in his new team's offense. Women's basketball head coach Ashley Langford talks about the differences on starting her second year as opposed to her first, and forward Amira Mabry on her impressive bag of tricks in year four. Then, football gets ready for UTSA as quarterback Jake Retzlaff looks at the offense's step forward in the passing game, and defensive lineman Geordan Guidry on stopping the electrifying Roadrunners' offense.See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Laurie Seymour & Curtis Williams: Getting Stronger in Business and Life with EOS

Better Business Better Life! Helping you live your Ideal Entrepreneurial Life through EOS & Experts

This week on Better Business, Better Life, Debra Chantry-Taylor sits down with Laurie Seymour, an EOS implementer, and Curtis Williams, her very first client and the owner of a thriving personal training studio.Curtis shares how the pandemic forced him to adapt, offering free Zoom classes that eventually evolved into a structured, scalable business model. Laurie, who found EOS after struggling with self-implementation, helped Curtis bring order and accountability into the business through tools like the Level 10 Meeting and the scorecard. Together, they reveal how EOS has transformed Curtis's gym into a model built for growth.The conversation also explores the personal side of their relationship, from Laurie regaining her health and strength through Curtis's training, to Curtis finding clarity and confidence as a leader. With insights on defining core values, staying the course with EOS, and planning for expansion, this episode is a masterclass in how structure and discipline create freedom.Whether you're running a small business or looking to scale, Laurie and Curtis's journey proves that with focus and the right tools, long-term success is well within reach.CONNECT WITH DEBRA: ___________________________________________ ►Debra Chantry-Taylor is a Certified EOS Implementer | Entrepreneurial Leadership & Business Coach | Business Owner►Connect with Debra: debra@businessaction.com.au ►See how she can help you: https://businessaction.co.nz/►Claim Your Free E-Book: https://www.businessaction.co.nz/free-e-book/ ____________________________________________ GUESTS DETAILS: ► Laurie Seymour - LinkedIn ► Laurie Seymour - EOS Worldwide ► Curtis Williams - LinkedIn► Life Techs Fitness Episode 239 Chapters: 00:00 – Introduction 00:53 – Background of the Guests 01:35 – Laurie's Journey to Becoming an EOS Implementer 05:48 – Curtis's Introduction to EOS09:00 – Implementing EOS in a Personal Training Business 12:40 – Challenges and Solutions in Implementing EOS13:37 – Impact of EOS on Business Operations27:16 – Personal and Professional Growth27:47 – Tips for Business Owners41:12 – Final Thoughts and Future Plans

Dawgman.com's Kim Grinolds was at Big Ten Media Days this week and he was able to catch up with current CBS media personality and former Washington Head Coach Rick Neuheisel for a look back at his time on Montlake, including the teams and players that he coached. They talked about the 2000 Rose Bowl season that was filled with what Neuheisel called 'really high highs' and then 'knocked back down to sea level' with Curtis Williams' injury. He also shared stories and anecdotes with Kim on the following UW players, coaches and department personnel: Roc Alexander, Cody Pickett, Jeremiah Pharms, Wil Hooks, Willie Hurst, Hakim and Mikal Akbar, Marques Tuiasosopo, Jerramy Stevens, John Anderson, Todd Elstrom, Paul Arnold, Anthony Vontoure, Derrell Daniels, Jimmy Newell, Chris Massey, Sam Blanche, Nick Olszewski, Ben Mahdavi, Spencer Marona, Pat Conniff, Anthony Kelley, Steve Axman, Claudine Low, and Tank (Terry) Johnson, who was involved in finding a kidney donor for Nate Robinson. And Rick definitely had a story or two about Nate! To learn more about listener data and our privacy practices visit: https://www.audacyinc.com/privacy-policy Learn more about your ad choices. Visit https://podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Clouds In The Sky They Will Always Be There For Me', el nuevo disco de Porridge Radio, es un álbum curioso. Refleja más que ningun otro la fuerza del conjunto; logra capturar la amistad que les une y cómo han aprendido a tocar y crear juntos. Sin embargo, nace del momento de mayor soledad de su líder y vocalista Dana Margolin. Agotada, triste y con el corazón roto enfrentó el proceso de composición como si fuera la primera vez. El resultado es un disco poético, intenso, y perfecto para las tardes grises y cortas del otoño.Playlist:Ducks Ltd. - Grim SymmetryThe Drums - I (Still) Don't Know How To LoveLos Punsetes, Los Planetas - Tu Puto GrupoMk.gee - ROCKMANSaya Gray - SHELL (OF A MAN)Faye Webster, Lil Yachty - Lego RingBenjamin Booker - LWA IN THE TRAILER PARKCurtis Williams, Mura Masa - Here With MeFKA twigs - Perfect StrangerKelly Lee Owens - SunshineConfidence Man - FAR OUTThe Blessed Madonna, Joy Anonymous, Danielle Ponder - Carry Me HigherFred again..,Joy Anonymous - peace u needPorridge Radio - AnybodyBon Iver - THINGS BEHIND THINGS BEHIND THINGSSufjan Stevens, Katia Labèque, Marielle Labèque, David Chalmin, Bryce Dessner - ReflexionEscuchar audio

Eternal Perspective: Prioritizing Spiritual over Temporal

Bro. Curtis Williams

Bro. Curtis Williams

Bro. Curtis Williams

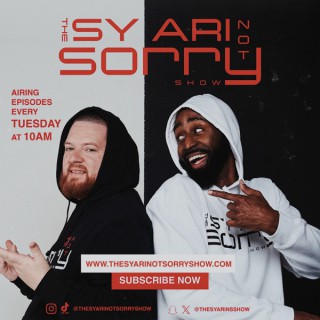

Episode 8 | "Edgewood Ave" (feat. Curtis Williams)

Subscribe - https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCT_JQHVrs_YqEf4nuIy9FBg @thesyarinotsorryshow In episode 8 "Edgewood Avenue" Sy Ari brings along special guest "Curtin Williams" of Two9 to discuss some of the legendary times on the different side of Atlanta and Edgewood avenue. https://linktr.ee/thesyarinotsorryshow To participate in WHYASKSY send your questions in a voice recording or video format from your phone to WHYASKSY@GMAIL.COM and also give us your name and city. Instagram & Tiktok: @TheSyAriNotSorryShow Twitter & Snapchat: @TheSyAriNSShow #SyAri

Louisville basketball: Kenny Payne should play the freshmen significantly this season!

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

Dalton discusses the Louisville basketball team's 91-50 win over Simmons College in the first exhibition game, and what head coach Kenny Payne said in his postgame press conference. He also explains why each of the four freshmen (Dennis Evans, Curtis Williams, Kaleb Glenn, Ty-Laur Johnson) should play significant roles for the Cardinals this season. Title Sponsor- PrizePicks Go to PrizePicks.com/lockedoncollege and use code lockedoncollege for a first deposit match up to $100! Daily Fantasy Sports Made Easy! Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors! Nutrafol Take the first step to visibly thicker, healthier hair. For a limited time, Nutrafol is offering our listeners ten dollars off your first month's subscription and free shipping when you go to Nutrafol.com/men and enter the promo code LOCKEDONCOLLEGE. DoorDash Get fifty percent off your first DoorDash order up to a twenty-dollar value when you use code lockedoncollege at checkout. Limited time offer, terms apply. PrizePicks Go to PrizePicks.com/lockedoncollege and use code lockedoncollege for a first deposit match up to $100! Daily Fantasy Sports Made Easy! Jase Medical Save more than $360 by getting these lifesaving antibiotics with Jase Medical plus an additional $20 off by using code LOCKEDON at checkout on jasemedical.com. Athletic Brewing Go to AthleticBrewing.com and enter code LOCKEDON to get 15% off your first online order or find a store near you! Athletic Brewing. Milford, CT and San Diego, CA. Near Beer. Gametime Download the Gametime app, create an account, and use code LOCKEDONCOLLEGE for $20 off your first purchase. LinkedIn LinkedIn Jobs helps you find the qualified candidates you want to talk to, faster. Post your job for free at LinkedIn.com/LOCKEDONCOLLEGE. Terms and conditions apply. FanDuel Make Every Moment More. Right now, NEW customers can bet FIVE DOLLARS and get TWO HUNDRED in BONUS BETS – GUARANTEED. Visit FanDuel.com/LOCKEDON to get started. FANDUEL DISCLAIMER: 21+ in select states. First online real money wager only. Bonus issued as nonwithdrawable free bets that expires in 14 days. Restrictions apply. See terms at sportsbook.fanduel.com. Gambling Problem? Call 1-800-GAMBLER or visit FanDuel.com/RG (CO, IA, MD, MI, NJ, PA, IL, VA, WV), 1-800-NEXT-STEP or text NEXTSTEP to 53342 (AZ), 1-888-789-7777 or visit ccpg.org/chat (CT), 1-800-9-WITH-IT (IN), 1-800-522-4700 (WY, KS) or visit ksgamblinghelp.com (KS), 1-877-770-STOP (LA), 1-877-8-HOPENY or text HOPENY (467369) (NY), TN REDLINE 1-800-889-9789 (TN) eBay Motors A championship team is about each player being a perfect fit. Same with your vehicle. So, for parts that fit, head to eBay Motors and look for the green check. Stay in the game with eBay Guaranteed Fit. eBay Motors dot com. Let's ride. eBay Guaranteed Fit only available to US customers. Eligible items only. Exclusions apply. Follow & Subscribe on all Podcast platforms…

Louisville basketball: Kenny Payne should play the freshmen significantly this season!

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

Dalton discusses the Louisville basketball team's 91-50 win over Simmons College in the first exhibition game, and what head coach Kenny Payne said in his postgame press conference. He also explains why each of the four freshmen (Dennis Evans, Curtis Williams, Kaleb Glenn, Ty-Laur Johnson) should play significant roles for the Cardinals this season.Title Sponsor-PrizePicksGo to PrizePicks.com/lockedoncollege and use code lockedoncollege for a first deposit match up to $100! Daily Fantasy Sports Made Easy!Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors!NutrafolTake the first step to visibly thicker, healthier hair. For a limited time, Nutrafol is offering our listeners ten dollars off your first month's subscription and free shipping when you go to Nutrafol.com/men and enter the promo code LOCKEDONCOLLEGE.DoorDashGet fifty percent off your first DoorDash order up to a twenty-dollar value when you use code lockedoncollege at checkout. Limited time offer, terms apply.PrizePicksGo to PrizePicks.com/lockedoncollege and use code lockedoncollege for a first deposit match up to $100! Daily Fantasy Sports Made Easy!Jase MedicalSave more than $360 by getting these lifesaving antibiotics with Jase Medical plus an additional $20 off by using code LOCKEDON at checkout on jasemedical.com.Athletic BrewingGo to AthleticBrewing.com and enter code LOCKEDON to get 15% off your first online order or find a store near you! Athletic Brewing. Milford, CT and San Diego, CA. Near Beer.GametimeDownload the Gametime app, create an account, and use code LOCKEDONCOLLEGE for $20 off your first purchase.LinkedInLinkedIn Jobs helps you find the qualified candidates you want to talk to, faster. Post your job for free at LinkedIn.com/LOCKEDONCOLLEGE. Terms and conditions apply.FanDuelMake Every Moment More. Right now, NEW customers can bet FIVE DOLLARS and get TWO HUNDRED in BONUS BETS – GUARANTEED. Visit FanDuel.com/LOCKEDON to get started.FANDUEL DISCLAIMER: 21+ in select states. First online real money wager only. Bonus issued as nonwithdrawable free bets that expires in 14 days. Restrictions apply. See terms at sportsbook.fanduel.com. Gambling Problem? Call 1-800-GAMBLER or visit FanDuel.com/RG (CO, IA, MD, MI, NJ, PA, IL, VA, WV), 1-800-NEXT-STEP or text NEXTSTEP to 53342 (AZ), 1-888-789-7777 or visit ccpg.org/chat (CT), 1-800-9-WITH-IT (IN), 1-800-522-4700 (WY, KS) or visit ksgamblinghelp.com (KS), 1-877-770-STOP (LA), 1-877-8-HOPENY or text HOPENY (467369) (NY), TN REDLINE 1-800-889-9789 (TN)eBay MotorsA championship team is about each player being a perfect fit. Same with your vehicle. So, for parts that fit, head to eBay Motors and look for the green check. Stay in the game with eBay Guaranteed Fit. eBay Motors dot com. Let's ride. eBay Guaranteed Fit only available to US customers. Eligible items only. Exclusions apply.Follow & Subscribe on all Podcast platforms…

Is Louisville finally getting the message? + Recruiting heating up

- What Kenny Payne can take from Jeff Walz- A quick disclaimer for the debbie downers- Louisville is definitely improving- What Manny Okorafor is bringing to the table- Key El Ellis stats- Jae'Lyn Withers showing improvements- Shoutout to UofL fans- Giving Kamari Lands his flowers- What we learned from FSU and GT- Where can UofL win to finish the season?- Recruiting is heating up- Names to watch in the transfer portal?- On comments from Trentyn Flowers and Curtis Williams+ much moreSubscribe to be the first to listen!Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brandsPrivacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Is Louisville finally getting the message? + Recruiting heating up

- What Kenny Payne can take from Jeff Walz- A quick disclaimer for the debbie downers- Louisville is definitely improving- What Manny Okorafor is bringing to the table- Key El Ellis stats- Jae'Lyn Withers showing improvements- Shoutout to UofL fans- Giving Kamari Lands his flowers- What we learned from FSU and GT- Where can UofL win to finish the season?- Recruiting is heating up- Names to watch in the transfer portal?- On comments from Trentyn Flowers and Curtis Williams+ much moreSubscribe to be the first to listen!

MLK Justice For Jayland Symposium Part II

Eight Akron police officers are currently under investigation for the June 27, 2022 killing of Jayland Walker, a 25-year-old African American young man. Officers fired more than 90 times at Jayland and his body was hit by 46 bullets.On Jan. 14, 2023 during MLK JFJ (#JusticeForJayland) weekend in Akron, OH, Rev. Mark moderated two panels on Where Do We Go From Here with Justice for Jayland Walker, Police Accountability, Police Violence, Black-on-Black Nonviolence, Trauma, Loss and Healing? The second panel included Bishop William J. Barber, founder of Repairers of the Breach ad the Poor People's Campaign; Dr. Lathardus Goggins, Principal Consultant at Applied Academic Solutions; Dr. Curtis Williams, II of the Minority Behavioral Health Group; Pastor Lori Porter of Love Akron; Pastor Kyle Early of the Cleveland Police Commission; Rev. Raymond Greene of Freeodom BLOC; Bishop Joey Johnson of Love and Justice Akron; Margo Sommerville, Akron City Council President; and Kenneth Brooks, youth activistAdvertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brandsPrivacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Monday Night Football: Bills/Bengals PPD after Damar Hamlin's collapse

HOUR 3: The latest on the condition of Damar Hamlin. Plus, Rick Neuheisel of CBS Sports joins DA to reflect on the Damar Hamlin collapse as well as his memories of seeing Curtis Williams injured first hand in 2000.

Bills/Bengals postponed after Damar Hamlin's collapse. Donovan Mitchell scores 70. Plus, Rick Neuheisel of CBS Sports joins DA to reflect on the Damar Hamlin collapse as well as his memories of seeing Curtis Williams injured first hand in 2000.

The Take 9-19-22 Hour 2 - The Show Feuds with Issel…

Andy and James discuss UK fans whining over the Ole Miss Kickoff time, Issel is mad at the show and there's a feud brewing, Stoops sound, UK football offense talk, the guys argue over Florida football, Emoni Bates talk, and Curtis Williams commits. See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Four-star small forward Curtis Williams Jr is a Louisville Cardinal! What's next for the 2023 class?

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

2023 four-star small forward Curtis Williams Jr committed to the Louisville Cardinals on Monday over Alabama, Xavier, Providence, and others. Dalton explains why Williams' skill set fits Kenny Payne's scheme and how his perimeter shooting will be a breath of fresh air for this program. With Kaleb Glenn and Curtis Williams Jr committed in the 2023 cycle, Dalton explains that the next spots will likely be given to a lead guard and a big man. DJ Wagner, AJ Johnson, Aaron Bradshaw, and Isaiah Miranda are four of the top options on Louisville‘s radar. in the final segment, Dalton discusses the Cardinals offering the top combo-guard in the 2024 class, Boogie Fland. The five-star holds offers from North Carolina, Duke, Kansas, Kentucky, and others. Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors! BetOnline BetOnline.net has you covered this season with more props, odds and lines than ever before. BetOnline – Where The Game Starts! Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Four-star small forward Curtis Williams Jr is a Louisville Cardinal! What's next for the 2023 class?

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

2023 four-star small forward Curtis Williams Jr committed to the Louisville Cardinals on Monday over Alabama, Xavier, Providence, and others. Dalton explains why Williams' skill set fits Kenny Payne's scheme and how his perimeter shooting will be a breath of fresh air for this program.With Kaleb Glenn and Curtis Williams Jr committed in the 2023 cycle, Dalton explains that the next spots will likely be given to a lead guard and a big man. DJ Wagner, AJ Johnson, Aaron Bradshaw, and Isaiah Miranda are four of the top options on Louisville‘s radar.in the final segment, Dalton discusses the Cardinals offering the top combo-guard in the 2024 class, Boogie Fland. The five-star holds offers from North Carolina, Duke, Kansas, Kentucky, and others.Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors!BetOnlineBetOnline.net has you covered this season with more props, odds and lines than ever before. BetOnline – Where The Game Starts! Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Cards Cast: Louisville basketball lands 4-star Curtis Williams

Cards Cast: A Louisville Cardinals football and basketball podcast

Cardinal Authority's Jody Demling and Michael McCammon discuss the commitment of four-star forward Curtis Williams to Louisville To learn more about listener data and our privacy practices visit: https://www.audacyinc.com/privacy-policy Learn more about your ad choices. Visit https://podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Could Curtis Williams Jr be the next Louisville basketball commit? Jamari Phillips, Gorgui Dieng

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

2023 four-star prospect Curtis Williams Jr has cut his list to four, with Louisville making the list alongside Florida State, Xavier, and Providence. He will be visiting the program in September ahead of his decision next month; the Cardinals' program is sitting in a great position in the recruitment.The Cardinals were also listed in the top-six for 2024 five-star Jamari Phillips. Kenny Payne and company have their work cut out for them in this recruitment, and the next step will be getting Phillips to visit.In the final segment, Dalton explains why he loves the San Antonio Spurs signing former Louisville star Gorgui Dieng to a one-year deal.Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors!BetOnlineBetOnline.net has you covered this season with more props, odds and lines than ever before. BetOnline – Where The Game Starts! Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Could Curtis Williams Jr be the next Louisville basketball commit? Jamari Phillips, Gorgui Dieng

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

2023 four-star prospect Curtis Williams Jr has cut his list to four, with Louisville making the list alongside Florida State, Xavier, and Providence. He will be visiting the program in September ahead of his decision next month; the Cardinals' program is sitting in a great position in the recruitment. The Cardinals were also listed in the top-six for 2024 five-star Jamari Phillips. Kenny Payne and company have their work cut out for them in this recruitment, and the next step will be getting Phillips to visit. In the final segment, Dalton explains why he loves the San Antonio Spurs signing former Louisville star Gorgui Dieng to a one-year deal. Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors! BetOnline BetOnline.net has you covered this season with more props, odds and lines than ever before. BetOnline – Where The Game Starts! Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Episode 119 - Kevin Brennan; Runner, Father, CPA, and Creator of the High Desert Dirt Blog

This week I had the pleasure to speak with Kevin Brennan. He is the creator of the High Desert Dirt Blog. He is also a father, a runner, and a CPA. Kevin is someone I've been wanting to talk to for a while. When I started this podcast and would do my research, his blog would constantly come up. He did much of the leg work work that I have relied on when researching many of the New Mexican Runners that came before our current crop. He talked about his early days running and we both reminisced about high school running. He talks about the great Gallup teams and their coach, Curtis Williams. He talks about having fun running in the arroyos of Santa Fe. Kevin also turns the table on me and asks me about getting into the podcast and my build up to Houston last year. It was fun to hear the things he thought about and where his mind went when creating content. It all felt very familiar. So check out the blog and perhaps he will get the creative bug again and produce some more content. I hope you enjoy our talk. Cross Country season is officially a week away. I hope you are able to support your local school and kids. It is also almost marathon season. I hope all your training is going well. So listen to your body, be smart, be safe, and keep running, New Mexico.

In this episode we sat down with artist, Curtis Williams, for an exclusive 1 on 1 conversation. We discussed everything from his collective, TWO-9, to hanging around legends like Kanye West, Asap Rocky, Virgil Abloh and so much more. Follow Curtis on all major platforms @thatboycurtis and stream his music everywhere! PATREON LINK: patreon.com/ogsessions FOLLOW US Instagram: @ogsessionspod Twitter: @ogsessionspod TikTok: @ogsessions

Can Louisville land 4-star Curtis Williams Jr? Cards offer 2024 5stars Elliot Cadeau & Carter Bryant

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

2023 four-star small forward Curtis Williams Jr recently told zagsblog.com that Louisville was recruiting him the hardest; the Cardinals have been prioritizing Williams ahead of his planned September decision. The program also recently offered two 2024 five-star prospects: PG Elliot Cadeau and SF Carter Bryant. Decision timelines are unclear, but Kenny Payne and staff will look to get both players on campus for visits in the respective future. At the end, Dalton conducts the weekly mailbag segment. Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors! BetOnline BetOnline.net has you covered this season with more props, odds and lines than ever before. BetOnline – Where The Game Starts! Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Can Louisville land 4-star Curtis Williams Jr? Cards offer 2024 5stars Elliot Cadeau & Carter Bryant

Locked On Louisville - Daily Podcast On Louisville Cardinals Football & Basketball

2023 four-star small forward Curtis Williams Jr recently told zagsblog.com that Louisville was recruiting him the hardest; the Cardinals have been prioritizing Williams ahead of his planned September decision.The program also recently offered two 2024 five-star prospects: PG Elliot Cadeau and SF Carter Bryant. Decision timelines are unclear, but Kenny Payne and staff will look to get both players on campus for visits in the respective future.At the end, Dalton conducts the weekly mailbag segment.Support Us By Supporting Our Sponsors!BetOnlineBetOnline.net has you covered this season with more props, odds and lines than ever before. BetOnline – Where The Game Starts! Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Working People: The fight to organize dollar store workers

From Dollar General and Dollar Tree to Family Dollar, dollar stores are spreading rapidly throughout Louisiana and across the country, often strategically located in low-income communities and “food deserts.” But dollar store workers notoriously have to endure low pay, understaffing, and hazardous working conditions; some workers report frequently working alone in stores and having their air conditioning controlled from corporate headquarters in another state. That's why Step Up Louisiana, "a community based organization committed to building power to win education and economic justice for all," is organizing employees, customers, and community members to fight for safer stores and better pay and working conditions for dollar store workers. In this episode, TRNN Editor-in-Chief Maximillian Alvarez speaks with Kenya Slaughter, who has been an organizer and frontline worker at Dollar General for a number of years, and Curtis Williams, a dollar store customer who has gotten involved in Step Up Louisiana's campaign.To read the transcript of this episode and read show notes, visit: https://therealnews.com/louisiana-dollar-store-workers-cant-control-air-conditioning-in-their-own-storesFeatured Music (all songs sourced from the Free Music Archive at freemusicarchive.org):Jules Taylor, "Working People Theme Song:Pre-Production/Studio: Maximillian AlvarezPost-Production: Jules TaylorHelp us continue producing radically independent news and in-depth analysis by following us and becoming a monthly sustainer: Donate: https://therealnews.com/donate-podSign up for our newsletter: https://therealnews.com/newsletter-podLike us on Facebook: https://facebook.com/therealnewsFollow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/therealnews

Dollar Store Workers Deserve Better (w/ Kenya Slaughter & Curtis Williams)

From Dollar General and Dollar Tree to Family Dollar, dollar stores are spreading rapidly throughout Louisiana and across the country, but dollar store workers notoriously have to endure low pay, understaffing, and hazardous working conditions. That's why Step Up Louisiana, "a community based organization committed to building power to win education and economic justice for all," is organizing employees, customers, and community members to fight for safer stores and better pay and working conditions for dollar store workers. In this episode, we speak with Kenya Slaughter, who has been an organizer and frontline worker at Dollar General for a number of years, and Curtis Williams, a dollar store customer who has gotten involved in Step Up Louisiana's campaign. Additional links/info below... Step Up Louisiana's website and Twitter page Kenya Slaughter, The New York Times, "I Never Planned to Be a Front-Line Worker at Dollar General" Permanent links below... Working People Patreon page Leave us a voicemail and we might play it on the show! Labor Radio / Podcast Network website, Facebook page, and Twitter page In These Times website, Facebook page, and Twitter page The Real News Network website, YouTube channel, podcast feeds, Facebook page, and Twitter page Featured Music (all songs sourced from the Free Music Archive: freemusicarchive.org) Jules Taylor, "Working People Theme Song

I walked the Camino for this special 3 part Camino podcast series this year where I interviewed many interesting people including fellow walkers, pilgrims, guides and historians.The Camino is over 800kms from the Spanish border in the Pyrenees to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia and it typically takes a walker between 30 to 35 to complete.In part 2 today I talk to Catharine Murphy who has walked the Camino many times and she gives us a great guide to the many ways to do the Camino. We then hear from my guides Fran and Ursula and then we finish off with an insightful interview with the American writer Curtis Williams on the history of the Camino.The Camino is a truly magical pilgrimage and I hope these 3 episodes convey in some small way why the Camino is so special to so many people around the world. We will have the final 3rd part of this special next Tuesday. For more information on the Camino go to the website https://www.spain.info .I flew with Aer Lingus from Dublin to Bilbao and then from Santiago to Dublin. If you haven't already I'd ask you to give me a follow on whichever platform you listen to your podcasts and you will be the first to get a new episode every Tuesday for the rest of the year.Fergal O'Keeffe is the host of Ireland's No.1 Travel Podcast Travel Tales with Fergal which is now listened to in 90 countries. The podcast aims to share soul-lifting travel memoirs about daydream worthy destinations. To find out who is on every Tuesday please follow me onWebsite www.https://www.traveltaleswithfergal.ieInstagram @traveltaleswithfergalFacebook @traveltaleswithfergalTwitter @FergalTravelYouTube @traveltaleswithfergal See acast.com/privacy for privacy and opt-out information.

I was fortunate to walk on the Camino in Spain in September for this special episode.The full Camino is over 800kms from the Spanish border in the Pyrenees to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia and it typically takes a walker between 30 to 35 days, walking around 25 km a day, to do the full Camino.The Camino is a truly magical experience that I would recommend to everyone but especially lovers of walking and history enthusiasts. The Camino brings you through four very different regions of Spain with four very distinct landscapes, culture, architecture, people, cuisine, weather and even language.The Camino is one of Christianity's most venerated and ancient pilgrimage walks and goes to the tomb of St James at the magnificent world heritage listed cathedral in Santiago de Compostela, which is the third most holy site in Christianity after Rome and Jerusalem.Today you will hear an interview from Fergal O'Keeffe on his Camino experiences, then Fergal interviews three writers John Connell, Mark O'Halloran and Curtis Williams about their Camino journeys.I hope these episodes convey in some small way why the Camino is so special to so many people around the world.There is an openness and camaraderie amongst fellow walkers, who share a passing “Buen Camino” greeting and they will often chat and exchange stories with you. Next Tuesday I will share those fascinating interviews with you and we will go a little deeper in the history and mystique of the Camino. For more information on the Camino go to the website https://www.spain.info.I flew with Aer Lingus from Dublin to Bilbao and then from Santiago to Dublin. If you haven't already I'd ask you to give me a follow on whichever platform you listen to your podcasts and you will be the first to get a new episode every Tuesday for the rest of the year.Fergal O'Keeffe is the host of Ireland's No.1 Travel Podcast Travel Tales with Fergal which is now listened to in 90 countries. The podcast aims to share soul-lifting travel memoirs about day-dream worthy destinations. To find out who is on every Tuesday please follow me onWebsite www.https://www.traveltaleswithfergal.ieInstagram @traveltaleswithfergalFacebook @traveltaleswithfergalTwitter @FergalTravelYouTube @traveltaleswithfergal See acast.com/privacy for privacy and opt-out information.

Stevie B. Acappella Gospel Music Blast - (Episode 231)

[2018 NACAMA National Academy Christian Acapella Music Artist Award] Stevie B. is playing the world's greatest acappella gospel music artists; the sweet sounds of voices. On tonight's show my special guest is Curtis Williams from Nashville, Tennessee. Curtis will be debuting some NEW Singles on the show tonight. "Song of the Week" featuring,... September (Monthly Triple Spin) featuring,... "Funny Bones" .... "Shout Outs" .... "Old One Hundreds" DATE: September 10, 2021

Taking a look at MSU's early Big Board for the 2023 class including prospects Braelon Green, Jeremy Fears, Jr., Jalen Hooks, Cam Christie, Curtis Williams, and Owen Freeman (among others).

SD Access For All

In this episode, Bob hangs out with Curtis Williams, SDPL's Technology Resources Manager and Sam Cerrato, the Circulation Supervisor at the Central Library. They discuss the new city-wide initiative, SD Access for All and the City of San Diego's efforts to address digital equity by getting the community connected via computer labs, devices, and various Wi-Fi hotspots. SD Access for AllInternet Services @SDPL Outdoor Computer LabsMobile Hotspot User GuideInternet Access Services @SDPL Wireless Computing @SDPL

Oklahoma County jail hostage situation leads to inmate death

Curtis Williams, an inmate at the Oklahoma County jail was fatally shot after a hostage situation on Saturday, March 27. Since then, the jail has faced backlash. The Oklahoman's reporters discuss. See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Oklahoma County jail hostage situation leads to inmate death

Curtis Williams, an inmate at the Oklahoma County jail was fatally shot after a hostage situation on Saturday, March 27. Since then, the jail has faced backlash. The Oklahoman's reporters discuss. See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

In this review, Kinge and Feefo discuss former Two-9 member Curtis Williams's 'Lightning McQueen' EP. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoicesSee omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

In this review, Kinge and Feefo discuss former Two-9 member Curtis Williams's 'Lightning McQueen' EP. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Astrology and Sign of the Times with Professional Astrology, Reiki Master, Shaman and Dream Analyst

Curtis Williams has been a practicing Humanistic Astrologer for over 28 years. He has received formal astrological training and certifications through Glenn Perry’s Academy of Astro Psychology and Noel Tyl’s Master’s Degree Course. His life experience and personal growth are what brought him to Astrology. Having suffered a life-changing injury as a young man, he continued on the path of self-discovery and healing through Astrology. Curtis has local, national, as well as international clientele and has expertise in many of the different levels of astrology such as Natal Astrology, Relocation Astrology, Horary Astrology, Couples Synastry, Mundane Astrology, and Rectification Astrology. As a supplement to his other healing modalities Curtis is also a Certified Medical Astrologer, a Shamanic Practitioner, Ecstatic Body Posture Instructor, Subtle Energy Artist and Dream Analyst. Curtis has been a Reiki practitioner since 2002. He holds Master/Teacher certifications in both Usui and Karuna Reiki®. He is a volunteer Reiki facilitator at the Hearst Cancer Research Center and the Homeless Shelter in San Luis Obispo, California. He participates in healing days and various clinics as well as being involved with several Reiki circles on a regular basis. He received his Master certifications for both Usui and Karuna Reiki® through the International Center for Reiki Training, which was founded by William Lee Rand. He received his first two levels in Usui Shiki Ryoho through the late Charlie Iron Eyes along with his wife Fe’ Iron Eyes. Curtis has completed and received his certification in E3 in May of 2009 from Dr William Mehring. E3 is a psychological and energy healing modality that specifically relates to and helps redirect physical, emotional, and traumatic events through personal transformation. E3 is a highly personalized approach to readdressing and examining past events that we all have experienced in our lives through the use of muscle testing, and finding resolution to problematic episodes that have been holding us back from successful relationships, and jobs. Curtis uses E3 as a transactional tool to finding core issues that directly relate to the health and diet such as allergies or overeating.If you are interested in classes or any reading, healing etc... here is Curtis'website https://astrologyreiki.com/about.htmlDon't forget to mention Psychic Babes to get $10 off!!!Support the show (http://www.psychicbabes.com/podcast)

Episode #38 | Squashin' Beefs | RIP Dustin Diamond aka Screech, Gamestop AMC Short Squeeze Drama

With a bunch of drama going down in the past week, including the Gamestop x AMC x Robinhood Short Squeeze issue, Dustin Diamond, who played Screech in Saved By The Bell, passed away, and Elon Musk hit Clubhouse, to name a few, we had to break it down for y'all. WhatD'YaReckon? received the first passes we've ever had, so clearly the questions are getting hectic. For the tunes, it was a big week. We got into new new from Sevana, M1llions, Westside Gunn x Armani Caesar, PartyNextDoor, Deanté Hitchcock x 6lack, Meek Mill x Leslie Grace x Boi-1da, Pink Sweat$ x Kehlani, Brent Faiyaz x DJ Dahi x Tyler, The Creator, 2 Eleven x Freddie Gibbs x Quincey White, Highup x Aryue x Snoop Dogg, Fredo x Dave, Eric Bellinger x Hitmaka, Curtis Williams x Sango x Palette, Michael Brun x Shay Lia, Rel McCoy, Ocean Wisdom x Maverick Sabre, FKA Twigs x Headie One x Fred Again, Jah Cure, Khurangbin x Knxwledge, Fat Joe x DJ Khaled x Amorphous, Lil' Wayne, Dave Hollister, Devin The Dude, and th1rt3en x Pharaohe Monch. Bam bam. ARTISTS: Contact info@illnotestudios.com for the production/mixing/mastering opportunity. Theme tune produced by Notion. Purchase beats: notionbeats.com Follow the team everywhere: @TheMovementFam @CeeFor @Notionbaby @iDahnJohnson

Louis The Child drops the last #PlaygroundRadio of 2020 featuring some amazing music from Kid Cudi, Machinedrum, Alison Wonderland & Valentino Khan, Whethan, Mia Gladstone and many more! 01. MIA GLADSTONE - GO [WEEKEND TRACK] 02. Louis The Child, COIN - Self Care 03. Death Cab for Cutie - I Dreamt We Spoke Again (Louis The Child Remix) 04. thomfjord - Interstellar 05. Alison Wonderland & Valentino Khan - Anything 06. Machinedrum - Kane Train (feat. Freddie Gibbs) 07. Kid Cudi - The Void 08. Amine, Unknown Mortal Orchestra - Buzzin 09. Jack Harlow - Funny Seeing You Here 10. Petit Biscuit - Parachute 11. Goth Babe - Moments / Tides 12. Curtis Williams, Palette, Mura Masa - A Rap About A Girl 13. Machinedrum - Wait 4 U (feat. Jesse Boykins III) 14. Whethan - In The Summer (feat. Jaymes Young) 15. Kid Cudi - Elsie's Baby Boy 16. Louis The Child - It's Strange (LeMarquis Remix) 17. Jim-E Stack - Be Long 2 18. Kid Cudi - Solo Dolo Pt III [PLAYGROUND PICK]

Episode 106:”Louie Louie” by the Kingsmen

Episode 106 of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs looks at “Louie Louie” by the Kingsmen, and the story of how a band that had already split up accidentally had one of the biggest hits of the sixties and sparked a two-year FBI investigation. Click the full post to read liner notes, links to more information, and a transcript of the episode. Patreon backers also have an eight-minute bonus episode available, on “It’s My Party” by Lesley Gore. Tilt Araiza has assisted invaluably by doing a first-pass edit, and will hopefully be doing so from now on. Check out Tilt’s irregular podcasts at http://www.podnose.com/jaffa-cakes-for-proust and http://sitcomclub.com/ —-more—- Resources As always, I’ve created a Mixcloud streaming playlist with full versions of all the songs in the episode. The single biggest resource I used in this episode was Dave Marsh’s book on Louie Louie. Information on Richard Berry also came from Marv Goldberg’s page, specifically his articles on the Flairs and Arthur Lee Maye and the Crowns. This academic paper on the song is where I learned what the chord Richard Berry uses instead of the V is. The Coasters by Bill Millar also had some information about Berry. Love That Louie: The Louie Louie Files has the versions of the song by the Kingsmen, Berry, Rockin’ Robin Roberts, and Paul Revere and the Raiders, plus many more, and also has the pre-“Louie” “Havana Moon” and “El Loco Cha Cha Cha” The Ultimate Flairs has twenty-nine tracks by the Flairs under various names. Yama Yama! The Modern Recordings 1954-56 contains twenty-eight tracks Richard Berry recorded for Modern Records in the mid-fifties, including the Etta James duets. And Have “Louie” Will Travel collects Berry’s post-Modern recordings, including “Louie Louie” itself. Patreon This podcast is brought to you by the generosity of my backers on Patreon. Why not join them? Transcript Today we’re going to look at what is arguably the most important three-chord rock and roll record ever made, a song written by someone who’s been a bit-part player in many episodes so far, but who never had any success with it himself, and performed by a band that had split up before the record started to chart. We’re going to look at how a minor LA R&B hit was picked up by garage rock bands in the Pacific Northwest and sparked a two-and-a-half-year FBI investigation, and was recorded by everyone from Barry White to Iggy Pop, from Motorhead to the Beach Boys, from Julie London to Frank Zappa. We’re going to look at “Louie Louie” by the Kingsmen: [Excerpt: The Kingsmen, “Louie Louie”] The story of “Louie Louie” begins with Richard Berry. We’ve seen Berry pop up here and there in several episodes — most recently in the episode on the Crystals, where we looked at how he’d been involved in the early career of the Blossoms, but the only time he’s been a signficant part of the story was in the episode on “The Wallflower”, back in March 2019, and even there he wasn’t the focus of the episode, so I should start by talking about his career. Some of this will be familiar from other episodes from a year or two ago, but here we’re looking at Berry specifically. Richard Berry was one of the many, many, great musicians of the fifties to go to Jefferson High School in Los Angeles, and was very involved in music at that school. When he arrived in the school, he had an aggressive attitude, formed by a need to defend himself — he walked with a limp, and had first started playing music at a camp for disabled kids, and he didn’t want people to think he was soft because of his disability. But as soon as he found out that you had to behave well in order to join the school a capella choir he became a changed character — he needed to be involved in music. And he soon was. He joined a group named The Flamingos, who were all students at Jefferson and proteges of Jesse Belvin, who was a couple of years older than them. That group consisted of Cornell Gunter on lead vocals, Gaynel Hodge on first tenor, Joe Jefferson on second tenor, Curtis Williams on baritone, and Berry on bass — though Berry was one of those rare vocalists who could sing equally well in the bass and tenor ranges, and in every style from gritty blues to Jesse Belvin style crooning. But as we’ve seen before, the membership of these groups was ever changing, and soon Curtis Williams left, first to join the Hollywood Flames, and then to join the Penguins. He was replaced, but Gunter and Berry left soon afterwards, and the remaining members of the band renamed themselves to The Platters. Berry and Gunter joined another group, the Debonairs, which was originally led by Arthur Lee Maye, with whom Berry would make many records over the years in the off-season — Maye was a major-league baseball player, and couldn’t record in the months his main career was taking up his time. Maye soon left the group, and in 1952 The Debonairs, with a lineup of Berry, Gunter, Young Jessie, Thomas Fox and Beverly Thompson, visited John Dolphin and made their first record, for Dolphins of Hollywood. The A-side featured Gunter on lead: [Excerpt: The Hollywood Blue Jays, “I Had a Love”] While the B-side featured Berry: [Excerpt: The Hollywood Blue Jays, “Tell Me You Love Me”] The group were disappointed when the record came out to discover that it wasn’t credited to the Debonairs, but instead to the Hollywood Blue Jays, a name Dolphin had also used for other groups. The record didn’t have any success, and so the group started looking for other labels that might record them. Cornell Gunter sat down with a pile of records and looked for ones with a label in LA. They decided to go with Modern Records, and ended up signed to Flair records, one of Modern’s subsidiaries. The label suggested they change their name to The Flairs, and they eagerly agreed, thinking that if their band had the same name as the label, the label would be more likely to promote them. Their first single for their new label was produced by Leiber and Stoller. One side was a remake of their first single, in better quality, with Gunter again singing lead, while the B-side was another Richard Berry song, “She Wants to Rock”: [Excerpt: The Flairs, “She Wants to Rock”] Apparently in 1953, when that came out, the title was still considered racy enough that the DJ Hunter Hancock insisted on them going on his radio show and explaining that by “rock” they merely meant to dance, and not anything more suggestive. Over the next couple of years, the Flairs would record and release tracks under all sorts of names — as well as many Flairs records they also released tracks as by The Hunters: [Excerpt: The Hunters, “Rabbit on a Log”] as Young Jessie solo records: [Excerpt: Young Jessie, “Lonesome Desert”] And as the Chimes. Several of these records were produced by Ike Turner, who by this point had moved on from working with Sam Phillips and was now working for the Bihari brothers, who owned Modern Records. Berry also released solo recordings, and recorded with a group led by Arthur Lee Maye, first as the Five Hearts (though there were only three of them at the time), then as the Rams, before the group settled down to become Arthur Lee Maye and the Crowns: [Excerpt: Arthur Lee Maye and the Crowns, “Set My Heart Free”] At one point in 1954, Berry was in three groups at the same time. He was in the Flairs, the Crowns, and the Dreamers — the group who became the Blossoms, who we talked about two weeks ago. And on top of that he was also recording a lot of sessions both as a solo singer, and as a duo with Jenell Hawkins, who also sometimes sang with the Dreamers: [Excerpt: Rickey and Jenelle, “Each Step”] The reason Berry was working on so many records wasn’t just that he loved singing, though he did, but because he’d learned from Jesse Belvin that it didn’t matter what the contract said, you were never going to get any royalties when you made records. So he sang on as many sessions as he could, pocketed his fifty-dollar fee, and then tried to get on another session. The Flairs eventually got sick of Berry working on so many other people’s records and singing with so many groups, and so he was out of the group — but he just formed his own new group, the Pharaohs, and carried on. The Flairs continued for years, though one at a time they left for other groups — Thomas Fox joined the Cadets, who had a hit with “Stranded in the Jungle”, and most famously, Cornell Gunter went on to join the classic lineup of the Coasters. But Berry actually sang on a Coasters record even before Gunter. As we saw, the first Coasters album was padded out with several singles by the Robins, credited to the Coasters, and one of the sessions that Berry had sung on was the Robins’ “Riot in Cell Block #9”, where Leiber and Stoller had asked him to sing lead, subbing for the Robins’ normal bass singer Bobby Nunn: [Excerpt: The Robins, “Riot in Cell Block #9”] The Bihari brothers were annoyed when they recognised Berry’s voice on that record — he was meant to be under contract to them, and even though he protested that it wasn’t him, they knew better. But they got Berry to start a solo career with a sequel to “Riot”, “The Big Break”, which he wrote himself: [Excerpt: Richard Berry, “The Big Break”] And for the next few years, Berry was promoted as a solo artist, recording songs like the Little Richard knockoff “Yama Yama Pretty Mama”: [Excerpt: Richard Berry, “Yama Yama Pretty Mama”] But of course that didn’t stop him from working with everyone else he could. Most famously, he was Henry on Etta James’ “The Wallflower”, which we looked at eighteen months ago: [Excerpt: Etta James and the Peaches, “The Wallflower”] Berry collaborated with James on the sequel, “Hey! Henry”, which was less successful: [Excerpt: Etta James, “Hey! Henry”] And he wrote “Good Rockin’ Daddy” for her, which made the R&B top ten: [Excerpt: Etta James, “Good Rockin’ Daddy”] This is all just scratching the surface. Between 1952 and the early sixties, Berry was on literally hundreds of records, under many names, and it’s likely we will never accurately know all of them. A fair number of them were classics of the genre, many more were derivative hackwork — quick knockoffs of the latest hit by Chuck Berry or Fats Domino, with the serial numbers not filed off all that well — and more than a few managed to be derivative hackwork *and* classics of the genre. Berry’s most famous song, “Louie Louie”, was both. There is nothing original about “Louie Louie”, yet it had an incalculable effect on popular music history, and Berry’s original version is a genuinely great record. The song had its genesis in a piece that Berry heard played as an instrumental by a group he was singing with at a gig one night, the Rhythm Rockers. When he asked them what the song was, he found out it was “El Loco Cha Cha Cha”, originally recorded by Rene Touzet. Berry loved the intro for the song, and immediately decided to rip it off: [Excerpt: Rene Touzet, “El Loco Cha Cha Cha”] That song is based around the same three-chord Latin groove as “La Bamba”, “Twist and Shout”, and roughly a million other songs, and so in keeping with the Latin feel of the song, Berry turned to another record as a model for his song. “Havana Moon” by Chuck Berry was the B-side to “You Can’t Catch Me”, and Richard Berry took its vocal melody, its lyrical theme of someone drinking while waiting for a ship to arrive and missing a girl who the narrator will see at the end of the boat journey, and its attempt at imitating Caribbean speech patterns by saying things like “Me stand and wait for boat to come”: [Excerpt: Chuck Berry, “Havana Moon”] Of course, nothing is original, and the Chuck Berry track itself was almost certainly inspired by Nat “King” Cole’s “Calypso Blues”: [Excerpt: Nat “King” Cole, “Calypso Blues”] Richard Berry took these influences, and turned them into “Louie Louie”, which he originally intended to have a Latin feel. But the owners of his record label wanted something more straight-ahead R&B, so that’s what they got: [Excerpt: Richard Berry and the Pharaohs, “Louie Louie”] While Berry’s inspiration had been based on the I-IV-V-IV chord sequence that you get in “La Bamba”, “Louie Louie” didn’t actually use that precise sequence. I’m going to get into some music-theory stuff here, which I know some of you like and some of you detest, and so if you dislike that stuff skip forward a couple of minutes. If you take just the “Louie Louie” riff, and play it with the standard I-IV-V-IV chords, you get “Wild Thing”: [Excerpt: “Wild Thing” riff, piano] But Berry, in his arrangement, incorporated a second melody part, a little standard motif you get in a lot of blues stuff, the fifth, sixth, flattened seventh, and sixth of the scale, repeating: [Excerpt: motif, piano] The problem is that the normal way to use that motif is over a single chord. Berry was using it over three chords, and the flattened seventh note clashes with the V chord — if you’re playing in C, you’ve got a G chord, which is the notes G, B, and D, but that little motif has a B-flat note. So you get a B and a B-flat played together, which doesn’t sound great: [Excerpt: tonal clash, piano] Now, if you’re a rock guitarist from the late sixties onwards, the way you’d resolve that problem is to play power chords — power chords have just the root and fifth note, no third, so in this case you wouldn’t be playing the B. Problem solved. But this was the 1950s, and while there were a handful of records using power chords, when Berry was making his record in 1957, they weren’t particularly common. Also, Berry was a piano player rather than a guitarist, and so he went for a different option. Instead of playing the normal V chord, he used the I chord, with a seventh — so if you were to play it in the key of C, it would be C7 — but he played it in the second inversion, with the dominant in the bass. So if you were playing it in the key of C, the notes would be G-Bflat-C-E. So the bass riff is still the I-IV-V-IV riff, but the chords sound like this: [Excerpt: “Louie Louie” chords, piano] That wouldn’t be the solution that many later cover versions would use, but it worked for Berry’s record, which was released as the B-side to a version of “You Are My Sunshine”, and became a minor local hit: [Excerpt: Richard Berry and the Pharaohs, “Louie Louie”] By this time, Berry had left Modern Records, and “Louie Louie” was on a small label, Flip Records. Berry was twenty-one, he’d been a professional musician since he was sixteen and was thinking of getting married, and he was making so little money from his music that he took a day job, working at a record-pressing plant, smashing returned records. When “Louie Louie” started getting played on local radio, people started giving him a hard time at work, asking why he needed that job when he had a hit record, not understanding that he was making no money from it. He ended up being treated so badly that he quit that job And Flip Records started pressuring him to make follow-ups to “Louie Louie” rather than do anything new. He did come up with a great follow-up, “Have Love Will Travel”, but that wasn’t a hit: [Excerpt: Richard Berry and the Pharaohs, “Have Love Will Travel”] He got a few big gigs for a while off the back of his local hit, but he ended up working at the docks with his father — but he eventually had to quit that because his disability made it impossible for him to do it. In 1959, in order to pay for his wedding, he sold his songwriting rights to “Louie Louie” and several of his other songs to the owner of Flip Records, for $750 — he wanted to hold out for a full thousand, but he ended up settling for a lower amount. From that point on, he would still get paid his BMI royalties when the song was played on the radio — you couldn’t sell those rights — but he wouldn’t receive anything from record sales or sheet music sales, or use in films, or anything like that. But that didn’t matter. A song like “Louie Louie”, a three-chord B-side to a flop single from two years earlier, was hardly going to earn any real money, and seven hundred and fifty dollars was a lot of money. Berry was a working man who needed money, and anyway he was moving into soul music. “Louie Louie” was just another song he’d written, no more important than “Look Out Miss James” or “Rockin’ Man”, and while R&B fans in LA loved it (if you listen to the later version by the Beach Boys, or to Frank Zappa’s riffs on the song, you can tell they grew up listening to Berry’s original, not the later versions) it wasn’t going to ever be heard outside those people. And that would have been true, if it hadn’t been for Ron Holden. We’ve not talked about the Pacific Northwest’s music scene in the podcast so far, but it had one of the most vibrant and interesting music scenes in the US in the late fifties and early sixties, and much of the music that gets labelled garage rock or frat rock comes from that area. The closest parallel I can think of is Liverpool — another place where mostly-white musicians were performing their own versions of music made by Black musicians, and performing it on electric guitars. But anyone who became big from the area immediately moved somewhere else and became “an LA musician” or “a New York musician”, and the scene as a whole has never really had the attention it deserves. Ron Holden was one of the few Black musicians in that scene. In fact, he was a second-generation musician — his father, Oscar Holden, was known as “the father of Seattle jazz”, and had played with both Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton. Ron Holden led the most popular band in the Seattle area, the Thunderbirds, and in 1960, he had a top ten hit with a song called “Love You So”: [Excerpt: Ron Holden, “Love You So”] He didn’t have any follow-up hits, but as every musician from Seattle who had any success did, he moved away. He moved to LA, where he signed to Keen Records, where he recorded an entire album of songs written and produced by Keen’s new staff producer Bruce Johnston, including “Gee, But I’m Lonesome”, a song which was coincidentally also recorded around that time by Richard Berry’s old collaborators the Blossoms: [Excerpt: Ron Holden, “Gee But I’m Lonesome”] Holden was also the MC for the Ritchie Valens Memorial Concert which was the Beach Boys’ first major professional live performance. But before he left Seattle, he had introduced “Louie Louie” to the music scene there — he’d heard it on the radio in 1957 and worked up an arrangement with his band, and it had been a highlight of his shows. Once he left the city, so he wasn’t performing the song there, all the white bands in Seattle, and in nearby Tacoma, picked up on the song and added Holden’s arrangement of the song to their own sets. Holden — or rather his saxophone player Carlos Ward, who did the Thunderbirds’ arrangements — had made a crucial change to “Louie Louie”, one that made it simpler to play on the guitar, and thus suitable for the guitar-heavy music that was starting to predominate in the Pacific Northwest. Remember that Richard Berry had that second-inversion major seventh chord in there? [Excerpt: “Louie Louie” chords, piano] Ward changed that chord for a simpler minor V chord, just flattening the third so there was no clash there: [Excerpt: “Louie Louie” chords, Pacific Northwest version] That would be how almost every version of “Louie Louie” from this point on would be performed, because it was how they played it in the Pacific Northwest, because it was how Ron Holden and the Thunderbirds played it, and few of those bands had heard Richard Berry’s original record, just Ron Holden’s live performances of the song. But one band who based their version on Holden’s did listen to the original record — once Holden had brought the song to their attention. The Wailers — who are often referred to as “the Fabulous Wailers” to distinguish them from Bob Marley’s later, more famous group — were a group from Tacoma, which had a strong instrumental guitar band scene — most famously, the Ventures came from Tacoma, and a lot of the bands in the area sounded like that. In 1959, the Wailers recorded a self-penned instrumental, “Tall Cool One”, which made the top forty: [Excerpt: The Wailers, “Tall Cool One”] They didn’t have any other hits, but soon after recording that, they got in a local singer, Rockin Robin Roberts, who became one of the band’s three lead singers. The group had a residence at a local venue, the Spanish Castle, and a live recording of one of their sets there, released as the “Live at the Castle” album, shows that they were a hugely exciting live band: [Excerpt: The Fabulous Wailers, “Since You Been Gone”] The shows at that venue were so good that several years later one of the regular audience members, Jimi Hendrix, would commemorate them in the song “Spanish Castle Magic”: [Excerpt: The Jimi Hendrix Experience, “Spanish Castle Magic”] But it was their version of “Louie Louie” that became the template for almost every version that ever followed. For contractual reasons, it was released as a Rockin’ Robin Roberts solo record, but it was the full Wailers playing on the track. No-one else in the Pacific Northwest knew what the lyrics were — they’d all learned it from Ron Holden’s live performances, but Roberts had actually tracked down a copy of the Richard Berry record and learned the words. Which, if you look at what happened later, is rather ironic. Their version of the song came out on their own label, and had few sales outside their home area, but it would be one of the most influential records ever, because everyone else in the Pacific Northwest started copying their version, right down to Roberts’ ad-libbed shout as they go into the guitar solo: [Excerpt: Rockin’ Robin Roberts, “Louie Louie”] The Wailers struggled on for a few more years, but never had any more commercial success. Rockin’ Robin Roberts went on to become an associate professor of biochemistry, before dying far too young in a car crash in 1967. But while their version of “Louie Louie” wasn’t a hit, a few copies made their way a couple of hours’ drive south, to Oregon. Here the story becomes a little difficult, because different people had different recollections of what happened. I’m going to tell one version of the story, but there are others. The story goes that one copy made its way into a jukebox at a club called the Pypo Club, in Seaside, Oregon, a club frequented by surfers. And one day in the early sixties — people seem to disagree whether it was summer 1961 or 62, two local bands played that club. During the intermission, the audience danced to the music on the jukebox — indeed, they danced to just one record on the jukebox, over and over. They just kept playing “Louie Louie” by Rockin’ Robin Roberts, no other records. Both bands immediately added the song to their sets, and it became a highlight of both band’s shows. By far the bigger of the two bands was Paul Revere and the Raiders. The Raiders actually came from Idaho, and had had a top forty hit with “Like, Long Hair” a novelty surf-rock version of a Rachmaninoff piece that Kim Fowley had produced: [Excerpt: Paul Revere and the Raiders, “Like, Long Hair”] But their career had stalled and they had moved to Oregon, because Revere, the group’s piano player and leader, had been drafted, and while he was allowed not to serve in the military because of his Mennonite faith, he had to do community service work there for two years instead. The Raiders were undoubtedly the best and most popular band in the Oregon area at the time, and their showmanship was on a whole other level from any other band — they were one of the first bands to smash their instruments on stage, except they weren’t smashing guitars — Revere would buy cheap second-hand pianos and smash *those* on stage. A local DJ, Roger Hart, had become the group’s manager, and he was going to start up his own label, and he wanted them to record “Louie Louie” as the label’s first single. Revere wasn’t keen — he didn’t like the song much, but Roger Hart insisted. He was sure it could be the hit that would restore the Raiders to the charts. So in April 1963, Paul Revere and the Raiders went into Northwest Recorders in Portland and recorded this: [Excerpt: Paul Revere and the Raiders, “Louie Louie”] Hart paid for the recording session and put the single out on his small label, Sande. It was soon picked up by Columbia Records, who put it out nationally. It started to get a bit of airplay, and started rising up the charts — it didn’t break the Hot One Hundred straight away, but it was clearly heading in the right direction. The Raiders signed to Columbia, and with Hart as their manager and occasional songwriter, and Terry Melcher as their producer, they became one of the biggest bands in the US, and had a string of hits stretching from 1965 to 1971. We won’t be doing a full episode on them, but they became an integral part of the LA music scene in the sixties, and they’re sure to turn up as background characters in future episodes. But note that I said their run of hits started in 1965. Because there had been two bands playing the Pypo Club, and they had both added “Louie Louie” to their set. And they’d both recorded versions of it in the same studio, in the same week. The Kingsmen were… not as big as the Raiders. They were a bunch of teenagers who had formed a group a few years earlier, and even on a good day they were at best the second-best band in Portland, with the Raiders far, far, ahead. The core of the group was based around the friendship of Jack Ely, the group’s lead singer, and Lynn Easton, the drummer, whose parents were friends — both families were Christian Scientists and actively involved in their local church — and they had grown up together. Ely’s parents didn’t encourage the duo’s music — Ely’s biological father had been a professional singer, but when the father died and Ely’s mother remarried, his stepfather didn’t want him to have anything to do with music — but Easton’s did, and Easton’s father became the group’s manager. Easton’s mother even went to the local courthouse to register the group’s name for them. Easton’s father was replaced as their manager by Ken Chase, the owner of the radio station where Roger Hart was the most popular DJ, and they started pressuring him to make a record with them. Eventually he did — and he booked them into the same studio as the Raiders, the same week. Different people have different stories about which was first and which was second, but there is no doubt that they were only two days or so apart. And there’s also no doubt that they were very different in terms of professionalism. The Kingsmen did their best to copy the Rockin’ Robin Roberts version, right down to his shout of “Let’s give it to them right now!” but it was shockingly amateurish. The night before, they’d done a live show which consisted of a single ninety-minute-long performance of “Louie Louie” with no breaks, and Ely’s voice was shot. The mic was positioned too high for him and he had to strain his throat, and his braces were also making him slur the words. At one point early in the song, Easton clicks his drumsticks together by accident, and yells an obscenity loud enough to be captured on the tape: [Excerpt: The Kingsmen, “Louie Louie”] After the solo, Ely comes back in, wrongly thinks he’s come in in the wrong place, and stops, leaving Easton to quickly improvise a drum fill before they pick up again: [Excerpt: The Kingsmen, “Louie Louie”] The difference with the Raiders can be summed up most succinctly by what happened next — the Raiders’ manager paid for their session, but when the engineer at this session asked who was paying, and the Kingsmen pointed to their manager, he said “No, I’m not. I’ve not got any money”, and the members of the group had to dig through their pockets to get together the fifty dollars themselves. It’s incompetent teenagers, who have no idea what they’re doing, and it would become one of the most important records of all time. But when it was released… well, it was the second-best version of “Louie Louie” recorded in Portland that week, so while the Raiders were selling thousands, the Kingsmen only sold a couple of hundred copies. Jerry Dennon, the owner of the tiny label that released it, tried to get it picked up by Capitol Records, who rejected it saying it was the worst garbage they’d ever heard. He also sent it out to bigger indie labels, like Scepter, who stuck it in a drawer and forgot about it. And that was basically the end of the Kingsmen. In August, Easton decided that he was going to stop being the drummer and be the lead singer instead — he told Ely that Ely was going to be the drummer now. The other band members were astonished, because Easton couldn’t sing and Ely couldn’t play the drums, and they said that wasn’t going to happen. Easton then played his trump card — when his mother had registered the band name, she’d registered it just in his name. If they didn’t do things his way, they weren’t going to be in the Kingsmen any more, and he was going to find new Kingsmen to replace them. Ely and a couple of other members quit, and that was the end of the group. And then, in October, as the Raiders’ record was still slowly making some national progress, Arnie “Woo Woo” Ginsburg heard the Kingsmen’s version. This Arnie Ginsburg isn’t the Arnie Ginsburg we heard about in the episode on “LSD-25”, and who we’ll be meeting again briefly next week. This one was a DJ in Boston, and the most popular DJ in the area. And he *hated* the record. He hated it so much, he played it on his show, because he had a slot called The Worst Record Of The Week. He played it twice, and the next day, he had fifty calls from record shops — customers had been coming in wanting to know where they could get “Louie Louie”. Marv Schlachter at Scepter heard from the distributors how well the record was doing and picked it up for national distribution on their Wand subsidiary. In its first week on Wand, the single sold twenty-one thousand copies in Boston. [Excerpt: The Kingsmen, “Louie Louie”] For a few weeks, the Raiders and the Kingsmen both hung around the “bubbling under” section of the charts — the Raiders selling and being played on the West Coast, and the Kingsmen on the East. By the ninth of November, the Kingsmen were at eighty-three in the charts, while the Raiders were at 108. By December the fourteenth, the Kingsmen were at number two, behind “Dominique” by the Singing Nun, a Belgian nun singing in French: [Excerpt: The Singing Nun, “Dominique”] You might think that there could not be two more different records at the top of the charts, and you’d mostly be right, but there was one thing that linked them — the Singing Nun’s song had a chorus that went “Dominique, nique, nique”, and one of the reasons it had become popular was that in France, but not in Belgium where she lived, “nique” was a swear word, an expletive meaning “to fornicate”, roughly the French equivalent of the word that Lynn Easton shouted when he clicked his drumsticks together. So a big part of its initial popularity was because of people finding an obscene meaning in the lyrics that simply wasn’t there. And that was true of “Louie Louie” as well. Jack Ely had slurred the lyrics so badly that people started imagining that there must be dirty words in there, because otherwise why wouldn’t he be singing it clearly? People started passing notes in schools and colleges, saying what the lyrics “really” were — apparently you had to play the single at 33RPM to hear them properly. These lyrics never made any actual sense, but they were things like “We’ll take her and park all alone/She’s never a girl I lay at home/At night at ten I lay her again” and “on that chair I’ll lay her there/I felt my boner in her hair” — the kind of thing, in short, that kids make up all the time. So obviously, they were reported to the FBI. And obviously the FBI spent two years investigating the song: [Excerpt: The Kingsmen, “Louie Louie”] They checked it anyway, of course, and reported “A comparison was made of the recording on the tape described above as specimen K1 with the recording on the disk, submitted by the Detroit Office and described as specimen Q3 in this case and no audible differences were noted.” On the FBI website, you can read 119 pages of memos from FBI agents (with various bits blacked out for security reasons), and read about them shipping copies of “Louie Louie” to labs (under special seal, in case they’d be violating laws about transferring obscene material across state lines and breaking the very law they were investigating), listening to the record at 33, 45, and 78 RPM and trying to see if they could make out the lyrics, comparing them to the published words, to the various samizdat versions being shared by kids, and to Berry’s record, and destroying the records after listening. They interviewed members of the Kingsmen and DJs, and they went to Scepter Records to get a copy of the original master tape, which they were surprised to discover was mono so left them no way of isolating the vocals. Meanwhile they were getting letters from concerned citizens doing things like playing the single at 78 RPM, making a tape recording of that at double speed, and then slowing it down, saying “at that speed the obscene articulation is clearer”. This went on for two years. At no point does any of these highly trained FBI agents listening over and over to “Louie Louie” at different speeds appear to have heard Lynn Easton’s yelled expletive, which unlike all these other things is actually on the record. Meanwhile, the Kingsmen went on to have one more top twenty hit, with only Easton and the lead guitarist left of the original lineup, and then continued to tour playing their hit. Jack Ely toured solo playing his one hit. The most successful member of the group was Don Gallucci, the keyboard player, who formed Don and the Goodtimes, who had a minor hit with “I Could Be So Good To You”: [Excerpt: Don and the Goodtimes, “I Could Be So Good To You”] Gallucci went on to produce Fun House for the Stooges, who would also of course later record their own version of “Louie Louie”, in which they sung those dirty lyrics: [Excerpt: the Stooges, “Louie Louie”] But then, nearly everyone did a version of the song — there are at least two thousand recordings of it. But, other than from radio play, Richard Berry was receiving no money from any of these. After his marriage ended, he’d quit working as a musician to raise his daughter, gone back to school, and taken a day job — but then he’d been further disabled in an accident and had ended up on welfare, while his song was making millions for the people who’d bought it from him for seven hundred and fifty dollars. He didn’t even understand why the song was popular — the only version that sounded like the record he’d wanted to make was the one by Barry White, another ex-Jefferson High student, who’d added the Latin percussion Berry had wanted to put on before he’d been told to make it more R&B. But in the eighties, things started to change. Some radio stations started doing all-Louie weekends, where for a whole weekend they’d just play different versions of the song, never repeating one. One of those stations invited Berry to do a live performance of the song with Jack Ely, backed by Bo Diddley’s former rhythm player Lady Bo and her band: [Excerpt: Richard Berry and Jack Ely, “Louie Louie”] That was the first time Berry ever met the man who’d made his song famous. Soon after that, Berry’s old friend Darlene Love, who had been one of the Dreamers who’d sung with Berry back in the fifties, introduced him to the man who would change his life — Chuck Rubin. Rubin had, in the seventies, been the manager of the blues singer Wilbur Harrison, and had realised that not only was Harrison not getting any money from his old recordings, nor were many other Black musicians. He’d seen a business opportunity, and had started a company that helped get those artists what they deserved — along with giving himself fifty percent of whatever they made. Which seems like a lot, but many people, including Berry, figured that fifty percent of a fortune was better than the hundred percent of nothing they were currently getting. Most of these artists had signed legally valid bad deals, which meant that while they were morally entitled to something, they weren’t legally entitled. But Rubin had a way of getting round that, and he did the same thing with Berry that he did with many other people. He kept starting lawsuits that put off potential business partners, and in 1986 a company wanted to use “Louie Louie” in a TV advertising campaign that would earn huge amounts of money for its owners — but they didn’t want to use a song that was tied up in litigation. If the legal problems weren’t sorted, they’d just use “Wild Thing” instead. In order to make sure the commercials used “Louie Louie”, the song’s owner gave Berry half the publishing rights and full songwriting rights (which Berry then split with Rubin). He didn’t get any back payment from what the song had already earned, but he went from getting $240 a month on welfare in 1985, to making $160,000 from “Louie Louie” in 1989 alone. Richard Berry died in 1997, happy, respected, and wealthy. In the last decade of his life people started to explore his music again, and give him some of the credit he was due. Jack Ely continued performing “Louie Louie” until his death in 2015. Lynn Easton quit music in 1968, giving the Kingsmen’s name to the lead guitarist Mike Mitchell, the only other original member still in the band. Easton died in April this year — no-one’s sure what of, as his religious beliefs meant he never saw a doctor. Mitchell’s lineup of Kingsmen continued to perform until covid happened, and will presumably do so again once the pandemic is over. And somewhere out there, whenever you’re listening to this, someone will be playing “duh-duh-duh, duh-duh, duh-duh-duh”

Episode 106:"Louie Louie" by the Kingsmen