Podcasts about Abbasid Caliphate

Third Islamic caliphate

- 67PODCASTS

- 88EPISODES

- 38mAVG DURATION

- 1MONTHLY NEW EPISODE

- Jan 15, 2026LATEST

POPULARITY

Best podcasts about Abbasid Caliphate

Latest news about Abbasid Caliphate

- Enslaved Africans, an uprising and an ancient farming system in Iraq: study sheds light on timelines English – The Conversation - Aug 21, 2025

- Can Iraq’s Development Road project become its gateway to prosperity? Middle-East - May 4, 2025

- The Mongol siege that destroyed Baghdad’s House of Wisdom erased CENTURIES of knowledge NaturalNews.com - Jan 24, 2025

- Build a Canal from Kiel, Take Part in a Rising Culture, and Join The Royal Society of Archeology BoardGameGeek News | BoardGameGeek - Jan 15, 2025

- THE GOOD OLD DAYS OF ABBASID CALIPHATE Creativity on Medium - Nov 6, 2024

- New Medieval Books: Tajikistan’s National Epics Medievalists.net - Jun 6, 2024

- Medieval Baghdad: Rise and Fall of the City of Peace (Video) Ancient Origins - Mar 5, 2024

- Renegade Game Studios Unveils “Scholars of the South Tigris” Tabletop Gaming News - Nov 30, 2023

- Iraqis marvel at ancient Iraq in new 'Assassin's Creed' game Al-Monitor: The Pulse of The Middle East - Oct 5, 2023

- Iraqis Marvel At Ancient Iraq In New 'Assassin's Creed' Game IBT US to feedly - Oct 5, 2023

Latest podcast episodes about Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate stood as a vibrant center of commerce, technology, and learning from the 8th to the 13th centuries. At the heart of this Islamic dynasty was the House of Wisdom. It was an extraordinary institute that drew scholars from across the known world, which made Baghdad an unrivaled center of learning. It also preserved much of the knowledge of the ancient world when Europe was in decline. Learn more about the House of Wisdom and how it shaped the world on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily. Sponsors Quince Go to quince.com/daily for 365-day returns, plus free shipping on your order! Mint Mobile Get your 3-month Unlimited wireless plan for just 15 bucks a month at mintmobile.com/eed Chubbies Get 20% off your purchase at Chubbies with the promo code DAILY at checkout! Aura Frames Exclusive $35 off Carver Mat at https://on.auraframes.com/DAILY. Promo Code DAILY DripDrop Go to dripdrop.com and use promo code EVERYTHING for 20% off your first order. Uncommon Goods Go to uncommongoods.com/DAILY for 15% off! Subscribe to the podcast! https://everything-everywhere.com/everything-everywhere-daily-podcast/ -------------------------------- Executive Producer: Charles Daniel Associate Producers: Austin Oetken & Cameron Kieffer Become a supporter on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/everythingeverywhere Discord Server: https://discord.gg/UkRUJFh Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/everythingeverywhere/ Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/everythingeverywheredaily Twitter: https://twitter.com/everywheretrip Website: https://everything-everywhere.com/ Disce aliquid novi cotidie Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

In this episode of History 102, 'WhatIfAltHist' creator Rudyard Lynch and co-host Austin Padgett discuss medieval Islam's decline from the Abbasid collapse through Mongol invasions, exploring the intellectual shift from cosmopolitan rationalism to religious orthodoxy and the rise of Turkic military states. -- FOLLOW ON X: @whatifalthist (Rudyard) @LudwigNverMises (Austin) @TurpentineMedia -- TIMESTAMPS: (00:00) Intro (14:04) Early Islamic Tolerance & Arab Demographic Strategy (24:17) [SPONSOR BREAK] (26:36) The Abbasid Caliphate & Dar al-Islam (37:02) The Islamic Golden Age: Wealth & Intellectual Achievement (52:02) The Fall of the Abbasid Caliphate (1:06:57) Al-Ghazali's Intellectual Counter-Revolution (1:27:13) The Mystic Period: Sufism & Rumi (1:40:19) Umayyad Spain & The Mediterranean Shifts Christian (1:55:25) Seljuk Turks & The Battle of Manzikert (2:01:35) Muslim Conquest of India & The Mamluk Problem (2:10:48) Ibn Khaldun & The 120-Year Dynasty Cycle (2:26:09) Mongol & Tamerlane Devastation (2:32:16) The "Sensitive Warlord" Archetype & Conclusion Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

The Fall of the Roman Empire Episode 122 "The Vikings"

The Vikings transformed European history, impacted the worlds of both Byzantium and the Abbasid Caliphate, and even, some 500 years before Christopher Columbus, discovered North America. In this episode, I want to look at how and why the Viking diaspora first began, before moving to their initial impact on the world outside Scandinavia, especially on the Carolingians and the establishment of the Viking-Frankish state of Normandy.For a free ebook, maps and blogs check out my website nickholmesauthor.comFind my latest book, Justinian's Empire, on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk. For German listeners, find the German translation of the first book in my series on the 'Fall of the Roman Empire', Die römische Revolution, on Amazon.de. Finally check out my new YouTube videos on the fall of the Roman Empire.

35. Religious extremes and Islamic law in al-Andalus: Martyrs of Córdoba, Ziryab, and more

In episode 35, I talk about the voluntary martyrs of Córdoba, the Jewish convert Bodo, the Black musician Ziryab, the situation of the Abbasid Caliphate from its foundation to the year 861, and how Islamic justice worked. SUPPORT NEW HISTORY OF SPAIN: Patreon: https://patreon.com/newhistoryspain Ko-Fi: https://ko-fi.com/newhistoryspain PayPal: https://paypal.me/lahistoriaespana Bitcoin donation: bc1q64qs58s5c5kp5amhw5hn7vp9fvtekeq96sf4au Ethereum donation: 0xE3C423625953eCDAA8e57D34f5Ce027dd1902374 Join the DISCORD: https://discord.gg/jUvtdRKxUC Follow the show for updates on Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/newhistoryspain.com Or Twitter/X: https://x.com/newhistoryspain YOUTUBE CHANNEL: https://www.youtube.com/@newhistoryspain Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/new-history-of-spain/id1749528700 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7hstfgSYFfFPXhjps08IYi Spotify (video version): https://open.spotify.com/show/2OFZ00DSgMAEle9vngg537 Spanish show 'La Historia de España-Memorias Hispánicas': https://www.youtube.com/@lahistoriaespana TIMESTAMPS: 00:00 Hook 00:25 The Martyrs of Córdoba 08:35 Bodo, the Deacon who Became a Jew 11:25 Ziryab, the Influencer of Abd al-Rahman II's Court 18:01 The Abbasid Caliphate up to 861 25:03 Maliki Islamic Law and the Ulema 36:04 The Verdict: The Danger of Focusing on Exceptions 37:19 Outro

A Casa de Sabedoria, epicentro do saber no Império Abássida, nos ensina que a civilização é o mosaico de um tapete tecido por vozes diversas, desafiando a noção de que o progresso seja um privilégio ocidental-europeu, e nos convida a recriar seu espírito de tradução, escutar e colaborar em um mundo fragmentado, onde o futuro depende de nossa capacidade de unir línguas, lógicas e sonhos, como fizeram os sábios de Bagdá há mais de mil anos. Venha conosco numa jornada incrível pela história! Patronato do SciCast: 1. Patreon SciCast 2. Apoia.se/Scicast 3. Nos ajude via Pix também, chave: contato@scicast.com.br ou acesse o QRcode: Sua pequena contribuição ajuda o Portal Deviante a continuar divulgando Ciência! Contatos: contato@scicast.com.br https://twitter.com/scicastpodcast https://www.facebook.com/scicastpodcast https://instagram.com/scicastpodcast Fale conosco! E não esqueça de deixar o seu comentário na postagem desse episódio! Expediente: Produção Geral: Tarik Fernandes e André Trapani Equipe de Gravação: Citação ABNT: Imagem de capa: Freepik Para apoiar o Pirulla, use o Pix abaixo: pirula1408@gmail.com Em nome de Marcos Siqueira (primo do Pirulla) [caption id="attachment_65160" align="aligncenter" width="300"] QR code PIX[/caption] Site: https://www.pirulla.com.br/ Expotea: https://expotea.com.br/https://www.instagram.com/expoteabrasil/ Referências e Indicações Sugestões de literatura: Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society. Routledge, 1998. Al-Khalili, Jim. The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance. Penguin Books, 2011. Kennedy, Hugh. When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World: The Rise and Fall of Islam's Greatest Dynasty. Da Capo Press, 2005. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, “Abbasids,” Brill, 2012. Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates. Routledge, 2016. O’Leary, De Lacy. How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs. Routledge, 1949. Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. Science and Civilization in Islam. Harvard University Press, 1968. Fahd, Toufic. “Botany and Agriculture.” In Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, edited by Roshdi Rashed. Routledge, 1996. Morgan, Michael Hamilton. Lost History: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Scientists, Thinkers, and Artists. National Geographic, 2007. Said, Edward W. Orientalism. Penguin Books, 1978 (para crítica ao eurocentrismo). Saliba, George. Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. MIT Press, 2007. Sugestões de filmes: Documentário: "Science and Islam" (BBC, 2009 mas disponível em plataformas como YouTube (com legendas em inglês) apresentada pelo físico Jim Al-Khalili cujo trabalho serviu de fonte, ver acima) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W_1RSVo3dLg&ab_channel=BanijayScience O Físico (2013) tem na Amazon Prime, filme segue um jovem cristão europeu que viaja ao mundo islâmico no século XI para estudar medicina com Ibn Sina (Avicena) em Isfahan (Irã). Sugestões de vídeos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SxJ2OC7iXo0 1001 Inventions and the Library of Secrets Sugestões de links: Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Abbasid Caliphate,” disponível em: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/abbasid-caliphate. Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Bayt al-Ḥekma,” disponível em: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/bayt-al-hekma. Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Mathematics in Islam,” “Astronomy,” e “Cartography,” disponível em: https://iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Dinawari,” disponível em: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/dinawari. Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Baghdad,” disponível em: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/baghdad. Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Bayt al-Ḥekma,” disponível em: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/bayt-al-hekma. Sugestões de games: Assassin´s Creed: Mirage Prince of Persia Age of Empires 2 Crusader Kings 2/3 See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Abd al-Rahman was supposed to die with the rest of his family. When the Abbasid Caliphate overthrew the Umayyads in a brutal coup, they made sure to slaughter every last male heir—except one. Abd al-Rahman, barely twenty, escaped across the Middle East and North Africa with assassins hot on his trail. He swam rivers, crossed deserts, and vanished into legend. And just when the world thought his dynasty was gone, he returned—on horseback, sword in hand, to conquer a new kingdom at the edge of the known world. In tody's episode Ben and Pat tell the true story of the prince who fled a massacre and became a king. Of the founder of Muslim Spain. Of a man who turned exile into empire—and earned his name as The Falcon of Al-Andalus.

רס"ג והמשיח - The Reasons for Saadia Gaon's Messianic Speculation in the 10th Century Abbasid Caliphate

What was the historical context for Saadia's prediction that משיח would come in 965 CE

Letizia Osti, "History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature" (I. B. Tauris, 2024)

Abu Bakr al-Suli was an Abbasid polymath and table companion, as well as a legendary chess player. He was perhaps best known for his work on poetry and chancery, which would have a long-lasting influence on Arabic literature. His decades of service at the court of at least three caliphs give him a unique perspective as an historian of his own time, although he is often valued as an observer rather than an interpreter of events for posterity. In History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature (I. B. Tauris, 2024), Letizia Osti provides the first full-length English-language study devoted to al-Suli, illustrating how investigating the life, times and works of such a complex individual can serve as a fil rouge for tackling broader, contested concepts, such as biography, autobiography, court culture, and written culture. The result is an exploration of the ways in which the Abbasid court made sense of the past and, in general, of what 'historiography' means in a medieval Arabic context. Letizia Osti is Professor of Arabic Literature and Language at the University of Milan, where she has taught since 2007. She earned her PhD in Arabic Studies from the University of St. Andrews, and is a member of the School of Abbasid Studies and other scholarly societies. Her research has been published widely in journals such as the Journal of Abbasid Studies, the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Literatures, and she is the co-author of the 2013 study Crisis and Continuity at the Abbasid Court. Samuel Thrope is Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library of Israel. He earned his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. He is the translator of Iranian author Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 1963 Israel travelogue The Israeli Republic (Restless Books, 2017) and, with Dr. Domenico Agostini, of the ancient Iranian Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation (Oxford University Press, 2021). Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/intellectual-history

Letizia Osti, "History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature" (I. B. Tauris, 2024)

Abu Bakr al-Suli was an Abbasid polymath and table companion, as well as a legendary chess player. He was perhaps best known for his work on poetry and chancery, which would have a long-lasting influence on Arabic literature. His decades of service at the court of at least three caliphs give him a unique perspective as an historian of his own time, although he is often valued as an observer rather than an interpreter of events for posterity. In History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature (I. B. Tauris, 2024), Letizia Osti provides the first full-length English-language study devoted to al-Suli, illustrating how investigating the life, times and works of such a complex individual can serve as a fil rouge for tackling broader, contested concepts, such as biography, autobiography, court culture, and written culture. The result is an exploration of the ways in which the Abbasid court made sense of the past and, in general, of what 'historiography' means in a medieval Arabic context. Letizia Osti is Professor of Arabic Literature and Language at the University of Milan, where she has taught since 2007. She earned her PhD in Arabic Studies from the University of St. Andrews, and is a member of the School of Abbasid Studies and other scholarly societies. Her research has been published widely in journals such as the Journal of Abbasid Studies, the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Literatures, and she is the co-author of the 2013 study Crisis and Continuity at the Abbasid Court. Samuel Thrope is Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library of Israel. He earned his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. He is the translator of Iranian author Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 1963 Israel travelogue The Israeli Republic (Restless Books, 2017) and, with Dr. Domenico Agostini, of the ancient Iranian Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation (Oxford University Press, 2021). Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/literary-studies

Letizia Osti, "History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature" (I. B. Tauris, 2024)

Abu Bakr al-Suli was an Abbasid polymath and table companion, as well as a legendary chess player. He was perhaps best known for his work on poetry and chancery, which would have a long-lasting influence on Arabic literature. His decades of service at the court of at least three caliphs give him a unique perspective as an historian of his own time, although he is often valued as an observer rather than an interpreter of events for posterity. In History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature (I. B. Tauris, 2024), Letizia Osti provides the first full-length English-language study devoted to al-Suli, illustrating how investigating the life, times and works of such a complex individual can serve as a fil rouge for tackling broader, contested concepts, such as biography, autobiography, court culture, and written culture. The result is an exploration of the ways in which the Abbasid court made sense of the past and, in general, of what 'historiography' means in a medieval Arabic context. Letizia Osti is Professor of Arabic Literature and Language at the University of Milan, where she has taught since 2007. She earned her PhD in Arabic Studies from the University of St. Andrews, and is a member of the School of Abbasid Studies and other scholarly societies. Her research has been published widely in journals such as the Journal of Abbasid Studies, the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Literatures, and she is the co-author of the 2013 study Crisis and Continuity at the Abbasid Court. Samuel Thrope is Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library of Israel. He earned his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. He is the translator of Iranian author Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 1963 Israel travelogue The Israeli Republic (Restless Books, 2017) and, with Dr. Domenico Agostini, of the ancient Iranian Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation (Oxford University Press, 2021). Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/middle-eastern-studies

Letizia Osti, "History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature" (I. B. Tauris, 2024)

Abu Bakr al-Suli was an Abbasid polymath and table companion, as well as a legendary chess player. He was perhaps best known for his work on poetry and chancery, which would have a long-lasting influence on Arabic literature. His decades of service at the court of at least three caliphs give him a unique perspective as an historian of his own time, although he is often valued as an observer rather than an interpreter of events for posterity. In History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature (I. B. Tauris, 2024), Letizia Osti provides the first full-length English-language study devoted to al-Suli, illustrating how investigating the life, times and works of such a complex individual can serve as a fil rouge for tackling broader, contested concepts, such as biography, autobiography, court culture, and written culture. The result is an exploration of the ways in which the Abbasid court made sense of the past and, in general, of what 'historiography' means in a medieval Arabic context. Letizia Osti is Professor of Arabic Literature and Language at the University of Milan, where she has taught since 2007. She earned her PhD in Arabic Studies from the University of St. Andrews, and is a member of the School of Abbasid Studies and other scholarly societies. Her research has been published widely in journals such as the Journal of Abbasid Studies, the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Literatures, and she is the co-author of the 2013 study Crisis and Continuity at the Abbasid Court. Samuel Thrope is Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library of Israel. He earned his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. He is the translator of Iranian author Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 1963 Israel travelogue The Israeli Republic (Restless Books, 2017) and, with Dr. Domenico Agostini, of the ancient Iranian Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation (Oxford University Press, 2021). Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/new-books-network

Letizia Osti, "History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature" (I. B. Tauris, 2024)

Abu Bakr al-Suli was an Abbasid polymath and table companion, as well as a legendary chess player. He was perhaps best known for his work on poetry and chancery, which would have a long-lasting influence on Arabic literature. His decades of service at the court of at least three caliphs give him a unique perspective as an historian of his own time, although he is often valued as an observer rather than an interpreter of events for posterity. In History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature (I. B. Tauris, 2024), Letizia Osti provides the first full-length English-language study devoted to al-Suli, illustrating how investigating the life, times and works of such a complex individual can serve as a fil rouge for tackling broader, contested concepts, such as biography, autobiography, court culture, and written culture. The result is an exploration of the ways in which the Abbasid court made sense of the past and, in general, of what 'historiography' means in a medieval Arabic context. Letizia Osti is Professor of Arabic Literature and Language at the University of Milan, where she has taught since 2007. She earned her PhD in Arabic Studies from the University of St. Andrews, and is a member of the School of Abbasid Studies and other scholarly societies. Her research has been published widely in journals such as the Journal of Abbasid Studies, the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Literatures, and she is the co-author of the 2013 study Crisis and Continuity at the Abbasid Court. Samuel Thrope is Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library of Israel. He earned his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. He is the translator of Iranian author Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 1963 Israel travelogue The Israeli Republic (Restless Books, 2017) and, with Dr. Domenico Agostini, of the ancient Iranian Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation (Oxford University Press, 2021). Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/islamic-studies

Letizia Osti, "History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature" (I. B. Tauris, 2024)

Abu Bakr al-Suli was an Abbasid polymath and table companion, as well as a legendary chess player. He was perhaps best known for his work on poetry and chancery, which would have a long-lasting influence on Arabic literature. His decades of service at the court of at least three caliphs give him a unique perspective as an historian of his own time, although he is often valued as an observer rather than an interpreter of events for posterity. In History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature (I. B. Tauris, 2024), Letizia Osti provides the first full-length English-language study devoted to al-Suli, illustrating how investigating the life, times and works of such a complex individual can serve as a fil rouge for tackling broader, contested concepts, such as biography, autobiography, court culture, and written culture. The result is an exploration of the ways in which the Abbasid court made sense of the past and, in general, of what 'historiography' means in a medieval Arabic context. Letizia Osti is Professor of Arabic Literature and Language at the University of Milan, where she has taught since 2007. She earned her PhD in Arabic Studies from the University of St. Andrews, and is a member of the School of Abbasid Studies and other scholarly societies. Her research has been published widely in journals such as the Journal of Abbasid Studies, the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Literatures, and she is the co-author of the 2013 study Crisis and Continuity at the Abbasid Court. Samuel Thrope is Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library of Israel. He earned his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. He is the translator of Iranian author Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 1963 Israel travelogue The Israeli Republic (Restless Books, 2017) and, with Dr. Domenico Agostini, of the ancient Iranian Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation (Oxford University Press, 2021). Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices Support our show by becoming a premium member! https://newbooksnetwork.supportingcast.fm/biography

Letizia Osti, "History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature" (I. B. Tauris, 2024)

Abu Bakr al-Suli was an Abbasid polymath and table companion, as well as a legendary chess player. He was perhaps best known for his work on poetry and chancery, which would have a long-lasting influence on Arabic literature. His decades of service at the court of at least three caliphs give him a unique perspective as an historian of his own time, although he is often valued as an observer rather than an interpreter of events for posterity. In History and Memory in the Abbasid Caliphate: Writing the Past in Medieval Arabic Literature (I. B. Tauris, 2024), Letizia Osti provides the first full-length English-language study devoted to al-Suli, illustrating how investigating the life, times and works of such a complex individual can serve as a fil rouge for tackling broader, contested concepts, such as biography, autobiography, court culture, and written culture. The result is an exploration of the ways in which the Abbasid court made sense of the past and, in general, of what 'historiography' means in a medieval Arabic context. Letizia Osti is Professor of Arabic Literature and Language at the University of Milan, where she has taught since 2007. She earned her PhD in Arabic Studies from the University of St. Andrews, and is a member of the School of Abbasid Studies and other scholarly societies. Her research has been published widely in journals such as the Journal of Abbasid Studies, the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Literatures, and she is the co-author of the 2013 study Crisis and Continuity at the Abbasid Court. Samuel Thrope is Curator of the Islam and Middle East Collection at the National Library of Israel. He earned his PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 2012. He is the translator of Iranian author Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 1963 Israel travelogue The Israeli Republic (Restless Books, 2017) and, with Dr. Domenico Agostini, of the ancient Iranian Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation (Oxford University Press, 2021). Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

fWotD Episode 2838: Siege of Baghdad Welcome to Featured Wiki of the Day, your daily dose of knowledge from Wikipedia’s finest articles.The featured article for Monday, 10 February 2025 is Siege of Baghdad.The siege of Baghdad took place in early 1258 at Baghdad, the historic capital of the Abbasid Caliphate. After a series of provocations from its ruler, Caliph al-Musta'sim, a large army under Hulegu, a prince of the Mongol Empire, attacked the city. Within a few weeks, Baghdad fell and was sacked by the Mongol army—al-Musta'sim was killed alongside hundreds of thousands of his subjects. The city's fall has traditionally been seen as marking the end of the Islamic Golden Age; in reality, its ramifications are uncertain.After the accession of his brother Möngke Khan to the Mongol throne in 1251, Hulegu, a grandson of Genghis Khan, was dispatched westwards to Persia to secure the region. His massive army of over 138,000 men took years to reach the region but then quickly attacked and overpowered the Nizari Ismaili Assassins in 1256. The Mongols had expected al-Musta'sim to provide reinforcements for their army—the Caliph's failure to do so, combined with his arrogance in negotiations, convinced Hulegu to overthrow him in late 1257. Invading Mesopotamia from all sides, the Mongol army soon approached Baghdad, routing a sortie on 17 January 1258 by flooding their camp. They then invested Baghdad, which was left with around 30,000 troops.The assault began at the end of January. Mongol siege engines breached Baghdad's fortifications within a couple of days, and Hulegu's highly-trained troops controlled the eastern wall by 4 February. The increasingly desperate al-Musta'sim frantically tried to negotiate, but Hulegu was intent on total victory, even killing soldiers who attempted to surrender. The Caliph eventually surrendered the city on 10 February, and the Mongols began looting three days later. The total number of people who died is unknown, as it was likely increased by subsequent epidemics; Hulegu later estimated the total at around 200,000. After calling an amnesty for the pillaging on 20 February, Hulegu executed the caliph. In contrast to the exaggerations of later Muslim historians, Baghdad prospered under Hulegu's Ilkhanate, although it did decline in comparison to the new capital, Tabriz.This recording reflects the Wikipedia text as of 00:30 UTC on Monday, 10 February 2025.For the full current version of the article, see Siege of Baghdad on Wikipedia.This podcast uses content from Wikipedia under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.Visit our archives at wikioftheday.com and subscribe to stay updated on new episodes.Follow us on Mastodon at @wikioftheday@masto.ai.Also check out Curmudgeon's Corner, a current events podcast.Until next time, I'm neural Justin.

Se'adya Gaon: The Geonic Pillar of Al-Andalus - Jackson Gardner

Se'adya Gaon was a prominent rabbi, gaon, Jewish philosopher, and exegete who was active in the Abbasid Caliphate. Se'adya is the first important rabbinic figure to write extensively in Judeo-Arabic. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

In this episode of History 102, 'WhatIfAltHist' creator Rudyard Lynch and co-host Austin Padgett examine the medieval decline of Asia, analyzing how regions that were once the world's centers of culture, economics, and technology—particularly China, India, and the Islamic world—gradually lost their dominance between 1000-1500 AD. --

THIS WEEK! We are joined by Nicholas Morton, and we discuss his recent book "The Mongol Storm". How did the Mongols help reshape geopolitical area of the 13th Century middle east? How did empires such as the Ayubids, The Seljuk Turks, or the once mighty Abbasid Caliphate fall so easilly to the Mongol storm? And how did the Mongols deal with their recently conquered areas of the middle east? Find out This week on "Well That Aged Well".You can find professor Morton on social media here: Twitter/X: @NicholasMorto11Instagram: @nicholasmorton123Bluesky: @NicholasMorto11Support this show http://supporter.acast.com/well-that-aged-well. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

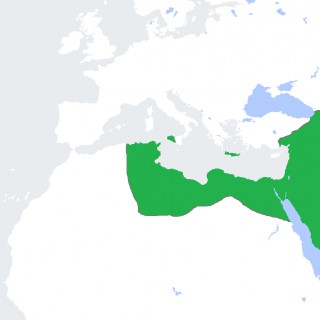

The Abbasid caliphate: everything you wanted to know

The Abbasid caliphs sat at the head of a vast Islamic empire that stretched from Tunisia to the frontiers of India, which they ruled over for several centuries. But how did they first come to power? What tools did they utilise to control such a significant swathe of land? And to what extent were they responsible for a 'Golden Age of Islam'? Speaking to Emily Briffett, Hugh Kennedy charts the rise and fall of a multicultural medieval empire and answers your top questions – on everything from the harem of the strictly structured court to the enormous amount of scholarship that flowed through the caliphate. The HistoryExtra podcast is produced by the team behind BBC History Magazine. Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

On this episode of Unsupervised Learning Razib talks to professor Sean Anthony about his book Muhammad and the Empires of Faith: The Making of the Prophet of Islam. Anthony is a historian in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at The Ohio State University. He earned his Ph.D. with honors in 2009 at the University of Chicago in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, and has a mastery of Arabic, Persian, Syriac, French, and German. Anthony's interests are broadly religion and society in late antiquity and medieval Islam, early canonical literatures of Islam (Koran and Hadith) and statecraft and political thought from the foundational period of Islam down to the Abbasid Caliphate over a century later. Razib and Anthony discuss the state of the controversial scholarship about the origins of Islam, which often comes to conclusions that challenge the orthodox Muslim narrative. This earlier generation of scholars, like Patricia Crone, challenged the historicity of Muhammad, the centrality of Mecca in early Islam and even the distinctive religious identity of the early 7th century's Near East's Arab conquerors. This revisionist school serves as the basis for Tom Holland's 2012 book, In the Shadow of the Sword: The Birth of Islam and the Rise of the Global Arab Empire. While Holland's work was an accurate summary of research before the 2010's, Anthony argues that since then new findings have updated and revised the revisionism itself. A Koran dating from the mid-7th century seems to confirm the antiquity of this text and traditions around it, while contemporaneous non-Muslim sources refer to Muhammad as an Arabian prophet. While it is true that coinage did not bear the prophet's name until the end of the 7th century, it may be that earlier generations of scholars were misled by the lack of access to contemporary oral sources themselves necessarily evanescent. Razib and Anthony also discuss whether the first Muslims actually self-identified as Muslims in a way we would understand, as opposed to being a heterodox monotheistic sect that emerged out of Christianity and Judaism. Though classical Islam qua Islam crystallized under the Abbasids after 750 AD, it now seems quite clear that the earlier Umayyads had a distinct identity from the Christians and Jews whom they ruled.

This episode of History 102 explores the fascinating rise of Islam, its Golden Age, and its decline, unpacking the cultural, political, and economic factors that shaped this pivotal period in history. WhatifAltHist creator Rudyard Lynch and Erik Torenberg talk about the cultural and scientific achievements of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliph - a period of unprecedented growth and innovation in the Islamic world. Then, uncover the reasons behind the decline of the Abbasid Caliphate, from internal conflicts and moral decay to the rise of the Turks and the shift from scientific progress to religious conservatism. – SPONSOR: BEEHIIV Head to Beehiiv, the newsletter platform built for growth, to power your own. Connect with premium brands, scale your audience, and deliver a beautiful UX that stands out in an inbox.

DRx Wilke's Holy Hermetic Heterodox Heresy

Tonight we are joined by DRx Wilke who runs the Holy Hermetic Heterodox Heresy channel on Youtube. The show is kicked off by audio of a "Pagan prayer to Thoth" from his channel of which he says the following about: We are the inheritors of the Gnostic Current as revealed to the seventh generation of Adam Kadmon in the Enochian Covenant, a recognized People of the Book as affirmed by the courts of the Abbasid Caliphate. We honor the 7 Noahide Laws of the righteous gentiles and keep the Golden Axiom: "To do good is only second, First do no harm." We preserve and protect the dwindling light of the mysteries and the cultus near extinguished at the close of Late Antiquity. Our messenger is the dual god Thoth-Hermes, called Hermes Trismegistus, first called Logos and Son of Man. We perceive Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus as the rightful heir to the Olympian Throne, as prophesied by the primordial Gaia regarding the line of titanic Metis. We likewise honor Metis' daughter Pallas Athena Minerva as Sophia to his Logos. We recognize the doctrine of metempsychosis, affirming the transmigration of souls, and acknowledge the unity of all as stated in the formula of the Emerald Tablet: “As above, so below”. You can check out the channel directly here: What *IS* the Holy Hermetic Heterodox Heresy? (youtube.com) #thoth #hermes #hermeticism #gnosticism #ifyouhaveghostsyouhaveeverything #alanbishopdistiller #alchemistoftheblackfores #thekinginyellow #keeperoftheblueflame --- Support this podcast: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/alan-bishop3/support

Cataloguing the tapestry of Islamic traditions is a task that lies well beyond our scope, but every now and again the topic overlaps with the subjects we are interested in. It's important to understand where the Qaramita and Fatimids came from, because these two foes will face the Abbasid Caliphate until its effective takeover by a rival dynasty. As these two communities emerged from Ismaili Shi'ism, we'll take the time to properly define and ground these terms before moving on. Please keep in mind that you are in no way getting a round-up of the religious or sectarian situation at the time; there were many more groups than the ones we're discussing. Refer back to the start of this paragraph for more information.

Al Mu'tamid's reign lasted from 870 to 892. The Abbasid Caliphate was reborn during these decades, midwifed by the caliph's brother Talha, better known in history by his title al Muwaffaq. The new Abbasid state understood its limits and adopted a pragmatic but uncompromising approach towards rebuilding its power. It developed formidable armies to fight off the many existential threats that faced it, then used this military edge to force its neighbors into relative submission.

The Golden Age of the Abbasid Caliphate

What if we told you that the teachings of Prophet Muhammad were considered radical at the time? As we journey through the intricate world of Islamic history, we take the time to demystify common misconceptions about Muslims and their beliefs. We'll shine a light on the life of Prophet Muhammad and the golden age of the Abbasid Caliphate. You'll be surprised to learn about the crusaders' siege of Nicaea, an action that seemed at odds with their Christian faith. Prepare to be fascinated as we dive into the rise and fall of the Seljuk Empire. The Seljuks left a significant imprint on the Islamic world, including the establishment of Islamic colleges and the flourishing of Persian culture under their rule. We'll also explore their military strategies, their transition from shamanistic beliefs to Islam, and the wider impact they had on the Islamic world. Join us in this riveting exploration of history's lesser-known chapters.Support the showShow Notes: https://www.thepithychronicle.com/resourceshttps://www.tiktok.com/@thepithychroniclershttps://www.instagram.com/the.pithy.chronicle/

INTERVIEW: Shohreh Aghdashloo on 'Assassin's Creed Mirage'

As the Assassin's Creed franchise returns to its roots in West Asia for Assassin's Creed: Mirage, allowing players to explore the splendor of Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate in the 9th Century, Ubisoft has recruited a Persian legend to help bring this story to life. An icon in Iranian and many other SWANA communities and beyond, Shohreh Aghdashloo has paved the way for SWANA actors to have roles that transcend beyond the stereotypes we're too often limited to, even though these nuanced roles for our communities remain highly limited. Aghdashloo has played many roles throughout her storied career, but it was clear, for many reasons as we spoke, that to take the role of the Persian Master Assassin Roshan, mentor of the main character Basim Ibn Ishaq (Lee Majdoub), had unique significance in Assassin's Creed: Mirage.

Muhammad ibn Isma'il al-Bukhari, commonly referred to as Imām al-Bukhāri or Imām Bukhāri, was a 9th-century Muslim muhaddith who is widely regarded as the most important hadith scholar in the history of Sunni Islam. Al-Bukhari's extant works include the hadith collection Sahih al-Bukhari, Al-Tarikh al-Kabir, and Al-Adab al-Mufrad. Born in Bukhara in present-day Uzbekistan, Al-Bukhari began learning hadith at a young age. He traveled across the Abbasid Caliphate and learned under several influential contemporary scholars. Bukhari memorized thousands of hadith narrations, compiling the Sahih al-Bukhari in 846. He spent the rest of his life teaching the hadith he had collected.

The Dabuyid Dynasty, otherwise known as the Gaubarid Dynasty, was an Iranian Zoroastrian Dynasty ruled by a group of independent kings, called Ispahbads. Most of what is known about the Dabuyid Dynasty is from the later historian Ibn Isfandiyar's Tarikh-I Tabaristan, written in the 13th Century. Although the dynasty was founded by Gil Gavbara in 642 CE, it was named after his son, Dabuya, who controlled the kingdom after his father's death. Dabuyid rule extended over Tabaristan and western Khorasan until the Abbasid conquest in 760. The dynasty ended with the suicide of Khurshid after a surprise invasion by the Abbasid Caliphate. Thank you to Amineh Najam-ud-din for this article.

That's History: The Mongol Horde And The Sacking Of The Ancient City Of Baghdad (8/24/23)

The sack of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258 was a devastating event in history that marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age and the destruction of one of the world's most splendid and culturally advanced cities. Here is a summary of the key points:Background: Baghdad was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, one of the most powerful and influential Islamic empires. At its height, the city was a center of learning, culture, and trade, known for its libraries, scholars, and wealth.Mongol Invasion: The invasion was led by Hulagu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan. He arrived in the region with a massive Mongol army, determined to conquer the Islamic heartland.Siege: In January 1258, the Mongols laid siege to Baghdad. The city was poorly prepared for the assault, and its defenses crumbled under the Mongol onslaught.Sack of the City: After a lengthy siege, the Mongols breached the walls of Baghdad in February 1258. The city fell, and what followed was a brutal and destructive rampage. Tens of thousands of residents were killed, and the city was plundered and set ablaze.Loss of Knowledge: One of the most tragic aspects of the sack was the loss of countless books and manuscripts from Baghdad's libraries and centers of learning. The Tigris River was said to have run black with ink from the countless books thrown into the river.End of the Abbasid Caliphate: The sack of Baghdad effectively ended the Abbasid Caliphate as a significant political and cultural force. Although nominal caliphs continued to exist, their power was greatly diminished.Impact on the Islamic World: The destruction of Baghdad had a profound and long-lasting impact on the Islamic world. It marked the beginning of a period of fragmentation and decline, with the center of Islamic power shifting to other regions.Legacy: The sack of Baghdad is often seen as a symbol of the destructive power of the Mongol Empire and its impact on world history. It also serves as a cautionary tale about the vulnerability of great civilizations to external forces.In summary, the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258 was a tragic and pivotal event that led to the destruction of a once-magnificent city and had far-reaching consequences for the Islamic world and world history.(commercial at 8:13)to contact me:bobycapucci@protonmail.comThis show is part of the Spreaker Prime Network, if you are interested in advertising on this podcast, contact us at https://www.spreaker.com/show/5080327/advertisement

That's History: The Mongol Horde And The Sacking Of The Ancient City Of Baghdad (8/23/23)

The sack of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258 was a devastating event in history that marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age and the destruction of one of the world's most splendid and culturally advanced cities. Here is a summary of the key points:Background: Baghdad was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, one of the most powerful and influential Islamic empires. At its height, the city was a center of learning, culture, and trade, known for its libraries, scholars, and wealth.Mongol Invasion: The invasion was led by Hulagu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan. He arrived in the region with a massive Mongol army, determined to conquer the Islamic heartland.Siege: In January 1258, the Mongols laid siege to Baghdad. The city was poorly prepared for the assault, and its defenses crumbled under the Mongol onslaught.Sack of the City: After a lengthy siege, the Mongols breached the walls of Baghdad in February 1258. The city fell, and what followed was a brutal and destructive rampage. Tens of thousands of residents were killed, and the city was plundered and set ablaze.Loss of Knowledge: One of the most tragic aspects of the sack was the loss of countless books and manuscripts from Baghdad's libraries and centers of learning. The Tigris River was said to have run black with ink from the countless books thrown into the river.End of the Abbasid Caliphate: The sack of Baghdad effectively ended the Abbasid Caliphate as a significant political and cultural force. Although nominal caliphs continued to exist, their power was greatly diminished.Impact on the Islamic World: The destruction of Baghdad had a profound and long-lasting impact on the Islamic world. It marked the beginning of a period of fragmentation and decline, with the center of Islamic power shifting to other regions.Legacy: The sack of Baghdad is often seen as a symbol of the destructive power of the Mongol Empire and its impact on world history. It also serves as a cautionary tale about the vulnerability of great civilizations to external forces.In summary, the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258 was a tragic and pivotal event that led to the destruction of a once-magnificent city and had far-reaching consequences for the Islamic world and world history.to contact me:bobycapucci@protonmail.comThis show is part of the Spreaker Prime Network, if you are interested in advertising on this podcast, contact us at https://www.spreaker.com/show/5003294/advertisement

伊斯蘭政權統治伊比利半島800年,留下的不只是考古遺址!從語言、建築、文化到藝術,阿拉伯與伊斯蘭元素早已深植於西班牙這個國家的DNA裡。這集我們從伊斯蘭的角度切入,聊聊安達魯西亞,特別著重在伊斯蘭時期的前半,以及當時伊比利半島甚至整個歐洲最重要的都市:哥多華。節目中我們會聊到以下這些問題—— 西班牙究竟受阿拉伯與伊斯蘭文化影響有多深? 伊斯蘭教如何進入伊比利半島,讓一個已經被推翻的王朝續命300年? 直布羅陀海峽最窄處不是才13公里寬嗎,為什麼不蓋一座橋或隧道把兩個大陸連起來? 哈里發、酋長(埃米爾)、蘇丹到底有什麼不同?哈里發國時期的哥多華有多厲害? 要真正認識西班牙,就不能不了解伊斯蘭教在它身上留下的印記。讓我們回到西元第七世紀的伊比利半島,發現來自阿拉伯半島的奧瑪雅王朝在此建立的輝煌過往吧! 簡易年表 711 齊亞德帶領摩爾人軍隊跨過直布羅陀海峽,進攻伊比利半島 750 奧瑪雅王朝滅亡,王室後代退守至伊比利半島 756–929 哥多華酋長國 Emirate of Córdoba 929–1031 哥多華哈里發國 Caliphate of Córdoba 來自阿拉伯語的西班牙語單字舉例 hatta → hasta 直到 inshallah → ojala 但願如此 al-Qasr → Alcázar 堡壘、宮殿 al hamra → Alhambra 紅色(的宮殿),阿罕布拉宮 哈里發、埃米爾和蘇丹有什麼不同? 哈里發(Caliph)意為「繼承者」,是先知穆罕默德的正統接班人、整個伊斯蘭世界宗教與政治的最高領導者,地位近似於皇帝、教宗。歷史上曾經統治大部分伊斯蘭世界、且稱領導人為哈里發的政權包括: 拉什敦哈里發國(Rashidun Caliphate,四大哈里發時期,632–661) 奧瑪雅哈里發國(Umayyad Caliphate,661–750) 阿拔斯哈里發國(Abbasid Caliphate,750–1258) 鄂圖曼帝國(1517-1924) 埃米爾(或稱酋長、大公,Emir)意為「指揮」,原本是由哈里發指派、管理特定地區的統治者,類似封建社會中親王、大公、分封王的概念,後來常被用來指地區性的伊斯蘭政權領導者。 蘇丹(Sultan)意為「權威」,指一個伊斯蘭國家政治性的統治者,目前也被用作許多伊斯蘭國家元首的頭銜。 白衣大食、黑衣大食與綠衣大食 中國古代典籍稱阿拉伯為大食,其中又按照衣著的顏色分為: 白衣大食:奧瑪雅王朝 Umayyad Dynasty 黑衣大食:阿拔斯王朝 Abbasid Dynasty 綠衣大食:法提馬王朝 Fatimad Dynasty ✅ 本集重點: (00:00:16) 前言:讓旅行超越踩點,以伊斯蘭文化串起安達魯西亞的旅程! (00:04:35) 這些西班牙文單字全部都來自阿拉伯文!西班牙到底受伊斯蘭文化影響多大? (00:10:10) 伊斯蘭政權如何進入伊比利半島,從穆罕默德說起,四大哈里發、奧瑪雅王朝與阿拔斯王朝 (00:15:51) 直布羅陀海峽,歐洲與非洲之間的跳板,才13公里蓋一座橋有那麼難嗎?奧瑪雅王朝如何開啟伊比利半島的伊斯蘭時代 (00:23:18) 哈里發國首都哥多華,穆斯林、基督教徒與猶太教徒相安無事,宗教多元學風鼎盛,甚至一度超越君士坦丁堡? (00:26:51) 旅行推薦:哥多華清真寺,還是哥多華大教堂?一望無際的馬蹄型拱門與紅白相間的獨特結構 (00:32:11) 清真寺以外:Roman Bridge、Calahorra Tower、Alcazar、Medina Azahara (00:36:02) 結語,下集預告 Show note https://ltsoj.com/podcast-ep148 Facebook https://facebook.com/travel.wok Instagram https://instagram.com/travel.wok 意見回饋 https://forms.gle/4v9Xc5PJz4geQp7K7 寫信給主廚 travel.wok@ltsoj.com 旅行熱炒店官網 https://ltsoj.com/

As the morning sun shines on the Golden Gate Palace, brother and sister Hisham and Asma prepare for the journey of a lifetime. It is 791 CE, and the Abbasid Caliphate is at the height of its power, stretching from India to North Africa. With over half a million inhabitants, its capital city of Madinat al-Salaam, also known as Baghdad, is the largest in the Islamic Empire, possibly the world. And it's only 30 years old.当晨曦照耀在金门宫时,希沙姆和阿斯玛兄妹正在为一生难忘的旅程做准备。现在是公元 791 年,阿拔斯哈里发正处于权力的顶峰,从印度一直延伸到北非。其首都古城萨拉姆(也称为巴格达)拥有超过 50 万居民,是伊斯兰帝国中最大的城市,可能是世界上最大的城市。而且才30岁。Asma and Hisham will leave at sunset for the hajj, the holy pilgrimage to Mecca. Most people make the journey when they're older and wealthier, but Hisham and Asma have wanted to make this journey together since they were children.Asma 和 Hisham 将在日落时分前往麦加朝圣地朝圣。大多数人在年长和富有的时候开始了这段旅程,但 Hisham 和 Asma 从小就想一起完成这段旅程。They intend to travel with the big hajj caravan that is protected by the caliph soldiers. The caliph Al-Rashid himself is also traveling with the caravan this year. The hajj caravan is like a massive mobile city, with soldiers, cooks, doctors and merchants, servants and enslaved people. The journey is long, with dangers like disease, robbery, and dehydration. Because of these perils, Hisham and Asma want to travel with the larger group— but a last-minute mishap threatens to undo months of careful planning.他们打算乘坐由哈里发士兵保护的大朝觐商队。哈里发拉希德本人今年也与大篷车同行。朝觐商队就像一个巨大的移动城市,有士兵、厨师、医生和商人、仆人和奴隶。旅途漫长,伴随着疾病、抢劫和脱水等危险。由于这些危险,Hisham 和 Asma 想和更多人一起旅行——但最后一刻的意外可能会让数月的周密计划化为乌有。When the siblings visit the market to check on the supplies they've purchased, the merchant tells them one of their camels has fallen ill, and he doesn't have any replacements.Without the camel, the siblings won't be able to depart with the caravan. They search the marketplace, bustling with people from different ethnic backgrounds, such as Persians, Arabs, Turks, Africans, and Indians, and following different religions like Islam, Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. The market sells everything from locally made pottery, Egyptian glass, and paper from Samarkand, to Chinese silk, gold from Africa, and fox fur from the distant north. But with the caravan leaving tonight, no one has a camel available.当兄妹俩去市场检查他们购买的物资时,商人告诉他们他们的一只骆驼病了,他没有任何替代品。没有骆驼,兄妹俩将无法离开与大篷车。他们搜索市场,熙熙攘攘的人群来自不同的种族背景,如波斯人、阿拉伯人、土耳其人、非洲人和印度人,信奉不同的宗教,如伊斯兰教、犹太教、基督教和祆教。市场出售各种商品,从当地制造的陶器、埃及玻璃和撒马尔罕的纸张,到中国的丝绸、非洲的黄金和遥远北方的狐皮。但是今晚大篷车离开,没有人有骆驼可用。Though the hajj is primarily a religious journey, the siblings have other, personal hopes for it. Hisham and Asma come from a wealthy family and both had tutors as children.Hisham is studying to become a scholar, progressing from Arabic grammar to Islamic law and Persian love poetry, then to Indian-inspired mathematics and Greek philosophy and medicine. With scholars from all over the empire traveling to Mecca and important intellectual centers on the way, the hajj is a great learning opportunity.虽然朝觐主要是一次宗教之旅,但兄弟姐妹对此还有其他个人希望。 Hisham 和 Asma 都来自一个富裕的家庭,从小都有家庭教师。Hisham 正在学习成为一名学者,从阿拉伯语法到伊斯兰法律和波斯爱情诗歌,然后是印度启发的数学和希腊哲学和医学。来自帝国各地的学者前往麦加和途中的重要知识中心,朝觐是一个很好的学习机会。Asma, meanwhile, has literary ambitions. As a woman, a life of formal scholarship is not available to her. Instead, she is honing her skills as a poet. She hopes to compose poetry about the journey that will catch the attention of important women in the city, and maybe even Queen Zubayda.The siblings split up to search for a camel. Hisham heads toward the library complex to ask the scholars' advice. An elderly scholar studying Galen and Hippocrates tells him how to treat a wound. An Aramaic translator from Damascus shares a list of useful herbs for upset stomach on the road. A Persian poet wants to share his latest poetry, but Hisham doesn't see how that will get him the camel for tonight, so he kindly refuses. As he says goodbye, they give him the names of important theology scholars to visit in Medina, on the way to Mecca. But to get there, he'll need a camel.与此同时,阿斯玛也有文学抱负。作为一名女性,她无法享受正规奖学金的生活。相反,她正在磨练自己作为诗人的技能。她希望创作有关旅程的诗歌,以引起城市中重要女性的注意,甚至可能引起祖拜达女王的注意。兄弟姐妹分手寻找骆驼。 Hisham 前往图书馆大楼征求学者们的意见。一位研究盖伦和希波克拉底的年长学者告诉他如何治疗伤口。来自大马士革的阿拉姆语翻译分享了一份在路上治疗胃部不适的有用草药清单。一位波斯诗人想分享他最新的诗歌,但 Hisham 不明白这将如何让他成为今晚的骆驼,所以他善意地拒绝了。在他告别时,他们给了他重要神学学者的名字,让他在前往麦加的途中去麦地那拜访。但要到达那里,他需要一头骆驼。Meanwhile, Asma visits an older, married cousin. An enslaved girl opens the door, and takes Asma to the women's quarters, where men cannot enter. Her cousin wants to hear Asma's latest poetry, but Asma tells her she's in a hurry and explains their predicament. She's in luck— her cousin's husband has a camel to offer them.With their arrangements secure at last, they make their final preparations. At the designated times for men and women, each performs a ritual ablution at one of Baghdad's many public bathhouses.与此同时,阿斯玛拜访了一位年长的已婚堂兄。一个被奴役的女孩打开门,把阿斯玛带到了男人不能进入的女性宿舍。她的表妹想听听阿斯玛最新的诗歌,但阿斯玛告诉她她很着急,并解释了他们的困境。她很幸运——她表哥的丈夫有骆驼可以送给他们。随着他们的安排终于确定下来,他们进行了最后的准备。在指定的男女时间,每个人都会在巴格达众多公共浴室之一进行仪式沐浴。As the sun sets, the city's criers announce the caravan's departure, and the townspeople flock to watch the pilgrims leave.太阳落山时,城市的告示者宣布商队出发,市民蜂拥而至观看朝圣者离开。

The Aghlabids were an Arab Dynasty of Emirs that ruled Ifriqya, a historical region consisting of Tunisia, Libya, and Algeria and parts of Southern Italy and Sicily, for about a century beginning in 800 CE. The Aghlabids gained power when Ibrahim al-Aghlab was appointed Emir of the region. Under Aghlabid rule, Ifriqya became the first autonomous state in the Abbasid Caliphate. The capital of Ifriqya was in the present-day Tunisian city of Kairouan, which became the most important center of academics in the Maghreb under Aghlabid rule. Aghlabid rule over Ifriqya ended around 900 CE when the Fatimids came to power. Thank you to Kirsten Mullin for this article.

075: Turkic Origins: Part Five: The Seljuks: Act 2

Once the Seljuks had taken over the last vestiges of the Abbasid Caliphate, they came into direct contact with the Fatimid Caliphate and the Roman Empire. Despite being outnumbered, the Seljuks proved themselves to be masters in the art of war and conquest. Within a few decades Seljuks had conquered the HolyLand, and most of Anatolia... suddenly taking their place on the world stage.The History of Modern Greece Podcast covers the events of the Greek People from the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Greek War of Independence in 1821-1832, through to the Greco-Turkish War from 1919 to 1922 to the present day.Website: www.moderngreecepodcast.comMusic by Mark Jungerman: www.marcjungermann.com

The Muslim soldiers of the Abbasid Caliphate prepare to face off with the Chinese soldiers of the Tang Dynasty.

The Abbasid caliphate (750-1258) and its associated "golden age of Islam" is famous for a range of achievements in science, literature, and culture. The preservations and translations of ancient Greek texts to Arabic and the flow of discussion, philosophy, the merging of Persian, Greek and Arabic thought with Islam the countless inventions and new paths in science, mathematics and astronomy. All these are more or less known widely. Huge achievements. A mass of ancient texts were preserved for our eyes thanks to Persian scientists. But what about...Pickles?! What do we know about this superb condiment I say?!!?Well let's try and get a sense of place and a starting point to our story!Baghdad was founded in 762 as The City of Peace.The Abbasid empire stretched from the edges of India to the borders of Europe. Baghdad was the heart of the Islamic world and the centre of political rule. It was also the centre of the Translation Movement, when scholars from around the world came together at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, translating ancient Greek and Roman texts on subjects like algebra, medicine, and astronomy. Music, poetry and art flourished. The society of the Abbasid Caliphate was diverse and open. Think of it a little bit like the “Citadel” in Game of Thrones.As a Metropolis of a vast empire, Baghdad it was a sprawling city with houses of main thoroughfares, connected by narrow, winding and shade-giving streets; all within earshot of the local mosque. Business and trade were kept to the main streets and public squares, bustling and noisy with its food stalls and many other traders. Gardens both public and private, were an imitation of paradise with attention and care to details. Huge water-raising machines could be seen pumping water from rivers into the fields and to the cities and houses.In this hugely influential cultural city al-Baghdadi was born in 1239AD. He was a scribe, and was a compiler of an early Arabic cookbook of the Abbasid period, The Book of Dishes. Originally with 160 recipes but later 260 more were added.Thank you and see you soon!Music by Pavlos Kapralos and Motion Array (Arabian Nights, Barren Sands)Support this show http://supporter.acast.com/the-delicious-legacy. If you love to time-travel through food and history why not join us at https://plus.acast.com/s/the-delicious-legacy. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

The Battle of Talas was a pivotal moment in history and one of the earliest engagements between Muslim and Chinese forces. This battle involved the forces of the new Abbasid Caliphate, going up against a resurgent Tang Dynasty. Both empires wanted to secure their hold over Central Asia and its valuable Silk Road routes. This episode discusses the origins of the two sides in this conflict.

Episode 98: The Fall Of The Abbasid Caliphate. With Peter Konieczny

In this weeks episode we take a look at the fall of the infamous Caliphate of The Abbasids, And the Mongol Conquest of Baghdad in 1258. What was the Abbasid Caliphate like in 1258? What caused the Mongols to sucseed in the conquest of Baghdad? Find out this week on "Well That Aged Well". With "Erlend Hedegart".Find Medievalist.net here:https://www.medievalists.net/Support this show http://supporter.acast.com/well-that-aged-well. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

In 751 A.D., the forces of Tang China, led by a Korean general, met a distant foe on a battlefield in what is now Kyrgyzstan: the Muslims of the Abbasid Caliphate.What resulted was a key turning point in human history, though one seldom appreciated in the Western world.

The Caliph al-Mahdi and Patriarch Timothy I had a famous debate at the height of the Abbasid Caliphate about the differences between Christianity and Islam, over a thousand years ago. It stands as one of the greatest examples of mutual understanding and respect between the two faiths.

Episode 90: The Fatimid Caliphate. With Jennifer Pruitt

In this episode we visit The 10th Century Islamic world, and the Fatimid Caliphate. We discuss how they rose to power, and their height and fall, and what their rule was like, from their arcitecthure and their rivalry with the Abbasid Caliphate. This week on "Well That Aged Well", With "Erlend Hedegart"- Links where you can find professor Pruitt here: https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/khamseen/short-form-videos/2020/al-aqmar-mosque/https://wisc.academia.edu/JenniferPruitthttps://arthistory.wisc.edu/staff/jennifer-pruitt/Support this show http://supporter.acast.com/well-that-aged-well. Our GDPR privacy policy was updated on August 8, 2022. Visit acast.com/privacy for more information.

The Abbasid Caliphate had made it so far East that they came face to face with another superpower in the east. The Chinese Tang Dynasty was also expanding its borders West, and when the two superpowers met in the narrow valley of Talas... the epic battle between the Chinese and the Arabs happened in the year 751.The History of Modern Greece Podcast covers the events of the Greek People from the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Greek War of Independence in 1821-1832, all the way through to the Greco-Turkish War from 1919 to 1922.Website: www.moderngreecepodcast.comMusic by Mark Jungerman: www.marcjungermann.com

750 - 945 - The Abbasid Caliphate marked the Golden Age of Arabic culture when Baghdad became the cultural and economical centre of the world, but many dynastic entities rose to power creating an empire of intense competition.

Abbasid Caliphate‘s Hegemony in the Mediterranean w. Dr Harry Munt

The Abbasid Caliphate existed for hundreds of years longer than its Islamic predecessors. Dr Harry Munt, University of York, returns to the show to explain their reign and longevity.

Widely regarded as Islam's Golden Age, the Abbasid Caliphate was best known for its immense contributions to science, literature, and religion. Modern Cameras, Algebra, Air Conditioner, 1001 Nights, Modern Medicine, Qandil Lamp, Water Clock, Irrigation Methods, and so so much more were all invented during the Abbasid Caliphate. Along with an intelligence surveillance network, massive cross-continental trade routes, and a sophisticated taxation system, the Abbasid Caliphate lasted nearly 500 years. Thank you to Heba Assem for sharing all your knowledge on this fascinating and immense empire. --- This episode is sponsored by · Anchor: The easiest way to make a podcast. https://anchor.fm/app

History of the Mongols SPECIAL: Islamization